A Star Chef’s Gumbo Breaks a Big Rule of New Orleans Cooking

A Star Chef’s Gumbo Breaks a Big Rule of New Orleans Cooking

(Bloomberg) -- Editor’s Note: As more people are working from home, Bloomberg Pursuits is running a weekly Lunch Break column that highlights a notable recipe from a favorite cookbook and the hack that makes it genius.

In the pantheon of chefs who are larger than life, Leah Chase stands tall. More than a year after her death, the queen of Creole cooking is still part of the conversation. The chef and owner of the legendary Dooky Chase in New Orleans was the inspiration for Tiana in Disney’s 2009 film, The Princess and the Frog. She also made news when she slapped Barack Obama’s hand when he visited her restaurant and tried to add hot sauce to her gumbo before tasting it. In 2016, she had a cameo in Beyonce’s Lemonade video, seated in a throne-like chair.

But Chase is most renowned for using food as a tool for activism decades before such platforms as Bakers Against Racism became popular. Chase advocated for Black culture early on, using her restaurant as a meeting place for such people as Rosa Parks.

“So much of the civil rights movement was planned at restaurants,” observes chef Marcus Samuelsson, a longtime friend of Chase’s. “She would say to people in the movement, ‘You can come to my restaurant,’ which was breaking the law. People hadn’t thought about food as a way to activate, but she did.”

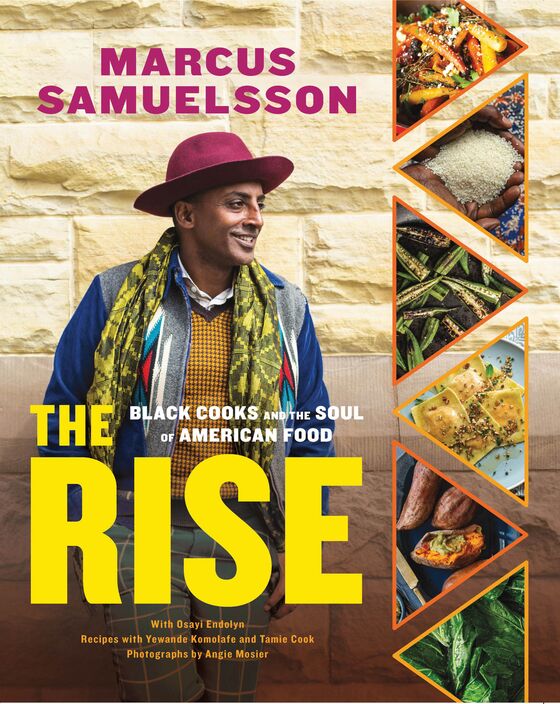

Samuelsson dedicates his new book, The Rise: Black Cooks and the Soul of American Food (Voracious; $38) to Chase. The cookbook, co-written with Osayi Endolyn, pays tribute to Black chefs, as well as to Black food writers who have told their stories. From cooks on the rise, such as Kwame Onwuachi and Houston’s Chris Williams, to storytellers like Jessica B. Harris and Devita Davison, Samuelsson includes profiles and recipes he created as an homage to them.

“This is an opportunity to create the most delicious conversation about race and culture,” says Samuelsson. “Unpack blackness. No one should be afraid to talk about it. And the best way to talk about it is through food.”

The book also highlights African ingredients and products that won’t be familiar to everyone, including berbere, a complex spice mix, and shito, a fiery hot sauce from Ghana, along with a directory of where to find them. Samuelsson believes that as Americans have become familiar with Korean food names—kimchi, bulgogi—they’ll learn about products such as awaze, an Ethiopian sauce that is compared with sriracha.

The most recognizable recipe in the book is Samuelsson’s ode to Leah Chase and her gumbo. But he takes a big, irreverent, if time-saving step and omits the flour—and, by extension, the roux—that is a staple of New Orleans gumbo, including Chase’s. Samuelsson stands firm on his decision, even as he acknowledges that purists might not consider his version a true gumbo. “I look at food from a flavor perspective,” he argues. “This gumbo has cleaner flavors without the flour, you can taste the essence of the dish: the red pepper, the seafood, the spices.”

He leans on filé powder, ground sassafras leaves, as a thickening agent instead. Inasmuch as a great gumbo is the sum of its many parts, this one does have distinct tastes: There’s complex heat from the cayenne, paprika, and chorizo, along with smoky sausage and sweet tomato. But no matter how much you want to believe in the thickening power of filé powder, it does only so much; the gumbo has a rich, happily oily broth, though it’s not especially thick, especially if you use frozen okra. (Samuelsson recommends simmering it down even more before adding the shrimp and sausage.)

Samuelsson says Chase would have slapped his hand, too, if she’d seen him making gumbo without flour.

“But she was also always about evolving. If there’s a flavor combination that’s better, she would have been for it,” he maintains. “She would have loved it when she tasted it.” But, he adds, “She would have said: ‘Just don’t put hot sauce on it.’ ”

The following recipe is adapted from The Rise: Black Cooks and the Soul of American Cooking, by Marcus Samuelsson, with Osayi Endolyn.

Ode to Leah Chase’s Gumbo

Serves 6 to 8

3 tbsp. vegetable oil

½ cup diced celery

½ cup diced red onion

½ cup diced red bell pepper

4 garlic cloves, minced

½ tsp. freshly ground black pepper

4 oz. ground chorizo

1 (14-ounce) can crushed tomatoes

12 oz. fresh or frozen okra, sliced

1 tbsp. smoked paprika

1 tbsp. filé powder (see Note)

1 tsp. cayenne pepper

2 cups fish stock or clam juice

2 cups chicken stock

2 tbsp. apple cider vinegar

1 lb. large shrimp, peeled and deveined

½ lb. smoked andouille sausage, sliced ¼ inch thick (see Note)

About 6 cups cooked rice, for serving

Chopped scallions, for serving

Chopped fresh parsley, for serving (optional)

Heat the vegetable oil in a large saucepan or Dutch oven set over medium-high heat until shimmering. Add the celery, onion, peppers, garlic, salt, and pepper and cook, stirring frequently, until the onion is translucent, 4-5 minutes. Add the chorizo and cook for 4 to 5 minutes, stirring frequently, until cooked through. Add the tomatoes, okra, paprika, filé powder, and cayenne and continue cooking for 4 to 5 minutes, stirring frequently. Add the stocks and vinegar and bring to a simmer. Decrease the heat to low, cover, and cook for 25 minutes, stirring occasionally.

Add the shrimp and andouille, and stir to combine. Continue to cook for 4 to 5 minutes, until the shrimp are just cooked through. Serve the gumbo over rice, topped with scallions and parsley.

Note: Filé powder is available at specialty food stores and by mail order. Andouille sausage is, too; if you can’t find it, you can substitute kielbasa and an additional pinch of cayenne pepper, according to famed New Orleans chef Paul Prudhomme.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.