Back in the Ring, Manny Pacquiao Battles the Ghost of Muhammad Ali

Back in the Ring, Manny Pacquiao Battles the Ghost of Muhammad Ali

(Bloomberg) -- Muhammad Ali is to boxing what William Shakespeare is to language, yet just as the sport delivered the “Louisville Lip” to the world stage, it also rendered him, by the end of his life, nearly unable to mumble a discernible sentence.

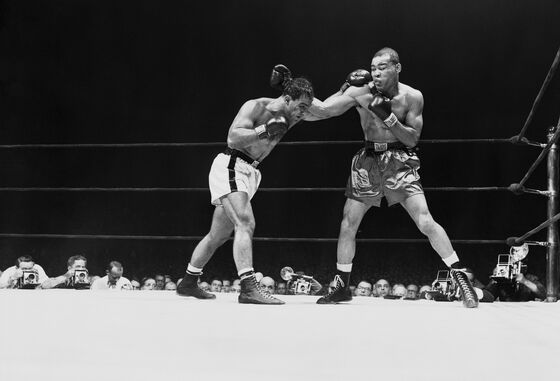

“Time is a vandal,” journalist Jimmy Cannon wrote. He watched his hero, Joe Louis, get beaten mercilessly into retirement by Rocky Marciano in 1951. Louis was Ali’s hero, too, and, in 1980, Louis went to Caesar’s Palace in his wheelchair and saw Larry Holmes brutalize Ali until Angelo Dundee finally stopped the beating.

Eight years later, in 1988, when Mike Tyson fought Holmes, Tyson’s childhood hero Ali was there to whisper in his ear: “Get him for me.” And Tyson did, knocking Holmes out in four rounds. Seventeen years later, at age 39, Tyson, two years after filing for bankruptcy, was fighting an unknown journeyman and quit on his stool after seven rounds.

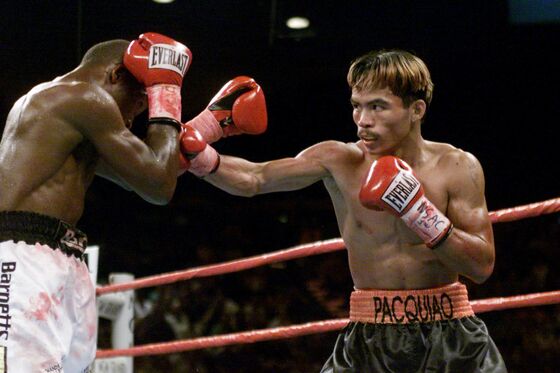

When Manny Pacquiao, 42—four years older than Ali was in 1980—gets into the ring against Yordenis Ugas at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas on Saturday, Aug. 21, he will be battling the ghosts of those greats before him as much as anyone wearing gloves and trunks. Since Pacquiao suffered a knockout loss against Juan Manuel Marquez at the end of 2012, he’s fought 10 more fights, winning eight, but not with his usual knockout power.

The fight will be aired on Fox PPV and features a guaranteed purse of $5 million for Pacquiao (with pay-per-view upside potentially adding $20 million to $25 million). It was slated to feature Pacquiao against undefeated world champion Errol Spence Jr. before a routine, pre-fight eye exam revealed Spence had a torn retina in his left eye. Pacquiao was a 2.5-1 underdog against Spence, and many experts viewed those odds as generous given the 31-year-old’s age and pedigree. WBA champion Yordenis Ugás, 35, has stepped in as a replacement for Spence on one of boxing’s largest stages—much as Pacquiao did two decades ago.

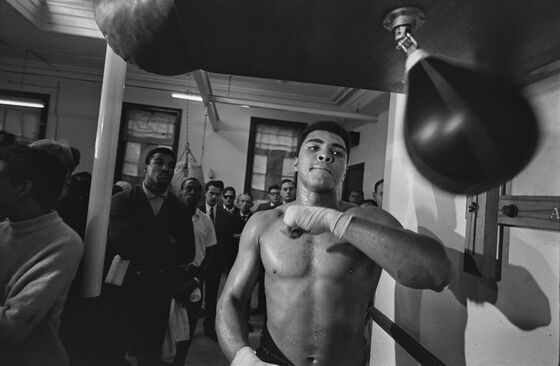

Pacquiao burst on the boxing scene in 2001, after he anonymously entered the front door of Freddie Roach’s Wild Card Boxing Club, located above a strip mall in Hollywood, Calif. The 22-year-old, five-foot-five, 112-pound Filipino had once sold doughnuts on the streets of General Santos City in the Philippines to survive before he turned to boxing.

With two weeks’ notice, he was an injury replacement on the undercard of an HBO pay-per-view championship fight against Oscar De La Hoya. That night, Pacquiao not only won a world title but also stole the show from one of the most marketable athletes in history. Seven years later, Pacquiao would electrify the sport by retiring Oscar De La Hoya in the exact same ring.

“I know what Ugás is feeling,” Pacquiao says. “Twenty years ago I was Ugás. I am taking him as seriously as I took Errol Spence.”

Pacquiao has fought 72 times across 27 years as a professional boxer. The talk among many fans and critics alike was that if Pacquiao were able, in the twilight of his career, to pull off a performance of the magnitude required to defeat Spence—in his prime, along with being bigger, stronger, younger—that résumé might well be unequalled in the annals of boxing.

Eight years ago, while Pacquiao was recovering from his brutal knockout loss by Marquez, I asked the late Leon Gast, Academy Award-winning director of When We Were Kings, who was then working on a documentary about the fighter, if he saw parallels between Ali and Pacquiao. “Déja vu all over again,” Gast said, shaking his head. “It’s boxing. Muhammad Ali fought 14 times after Zaire [where Ali pulled off one of the great upset victories in boxing history over George Foreman]. 14 times. God help us, here we go again.”

“Can he ever stop?” I asked.

“Never,” Gast said with a laughed. “Never, never, never.”

The answer Gast gave about why Pacquiao remained in the sport was the cliché: He needed the money. “Same old story,” Gast said. “Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, Ali, Tyson. All their careers ended with them either broke, busted up, or both.”

Thomas Hauser, author of Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, concurs with Gast’s assessment today, “The losses a great fighter suffers at the end of his career don’t hurt his legacy. A big win helps, but that rarely happens. In my view, Manny is fighting for the money. Period.”

Joe Louis, hopelessly addicted to cocaine and mired in debt over back taxes, spent the end of his life in a cowboy hat working as a greeter in front of Caesar’s Palace. Sonny Liston died alone, a week’s worth of newspapers and sour milk piled up outside the door. Joe Frazier spent his last days sleeping at the office of his gym. Leon Spinks cleaned toilets at the YMCA after his fighting days were over.

Mike Tyson, who earned $21 million for 91 seconds of work against Michael Spinks in 1988 while Michael Jordan made just over $2 million for an entire season on the basketball court, made more than $430 million in his professional boxing career and still went bankrupt before leaving the sport.

I ask Pacquiao if he worried about the last chapter of his career staining his legacy: “I’m not worried about that,” he says calmly. “It’s all about the sacrifices you’re willing to do and the dedication. You can avoid the punches and do what you want to do. He adds that “it’s a huge challenge at this age because I have to prove that I’m still here. I can still do what I was capable of doing before.”

Andre Ward, the last American male to win an Olympic Gold medal, in 2004, retired as an undefeated world champion in 2017 at the age of 33. Ward walked away from boxing with millions in the bank, and his health and mental faculties intact. Yet the temptation of potentially tens of millions of dollars remains on the table if he decides to return tomorrow.

Asked about his take on the Ali-Pacquiao comparison and how he navigated—and stayed true—to his own exit strategy, Ward says: “People only acknowledge the day you walked away,” Ward says from Oakland, Calif., where he now lives. “But that’s the easy part. The hard part is remaining true to your convictions for years later when you’re asked about it every day. When you’re pushed and prodded. People don’t see the emails or phone calls that I get. People don’t know that I can pick up the phone right now, and I’ll be right back in the spotlight and make tens of millions of dollars. The hard part is saying no to that every day.”

Ward says he understands why most don’t walk away. “It’s not something you ever want to think about,” he says. “I don’t know the personal demons each individual is wrestling with. I don’ t know where their self-esteem is. Guys don’t see a life beyond this sport. The other part of it is guys saying, ‘This is what I know. I may not be who I used to be, but I’m going to convince myself that what I have is enough.’”

Pacquiao has expressed desire to fight the best fighters in the world, such as Terence Crawford or Errol Spence Jr., if he’s victorious against Ugas on Saturday night. “I’m still here,” he says, smiling. “I’ll fight anybody.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.