The Artist Who Tried to Sink His Own Market and Almost Succeeded

The Artist Who Tried to Sink His Own Market—and Almost Succeeded

(Bloomberg) -- Clyfford Still was not an easy man.

He called the paintings of fellow abstract expressionist Barnett Newman “pathetic” and referred to influential art critic Clement Greenberg as “a small and lecherous man.” He destroyed one of his own canvases by cutting a chunk out of it after a collector dared to disobey his wishes. He turned down sales, rejected exhibitions, and forbade reproductions.

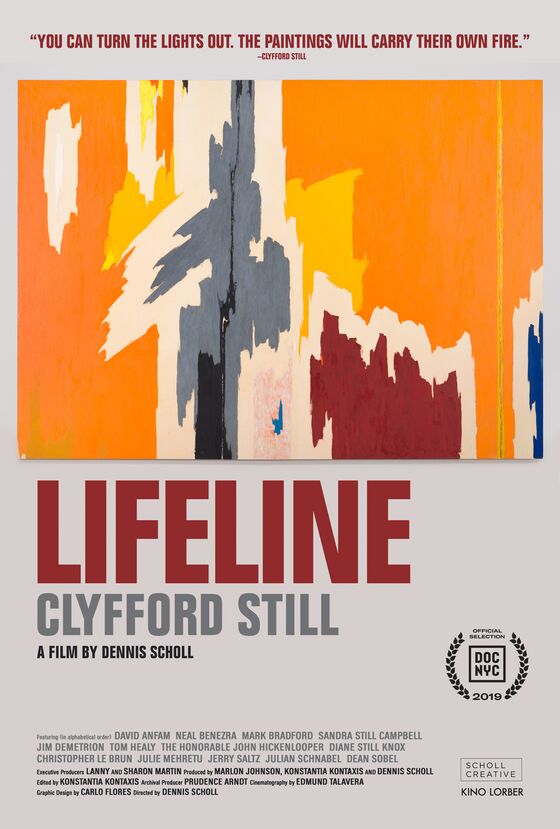

The artist’s uncompromising life and the toll it’s taken on his reputation and market is the subject of Lifeline, a new documentary premiering in New York on Nov. 12.

“It’s about what you give up in your life to make art the way you chose to,” says Dennis Scholl, the film’s director and an art collector. “He gave up acclaim and attention. He would not let the art world commodify him.”

Yet the art world might have had the last laugh. Sotheby’s will offer PH-399, painted in 1946, by Still at its marquee evening auction of contemporary art on Nov. 14, two days after Lifeline’s premiere. It’s estimated to sell for $12 million to $18 million.

Widely considered one of the greatest postwar American artists, Still has remained an enigma since he died in 1980.

The film tells his story through archival material, interviews with contemporary art stars such as Julian Schnabel and Mark Bradford, and insights from the artist’s two daughters. We see Still, always impeccably dressed in a white shirt and a tie, get into his Jaguar or approach a canvas that fills the entire field of vision.

His grave pronouncements, preserved in reel-to-reel audio, augment the narrative.

“When I hang a painting, I would have it say: ‘Here am I,’” Still says in one recording. “This is my presence. My feeling. My self. Here I stand. Implacable. Proud. Alive. Naked. Unafraid. If one doesn’t like it, he should turn away because I am looking at him.”

Still was just as dogmatic in death. His will stipulated that his estate be given to an American city willing to establish a permanent museum housing only his work. For the next three decades, hundreds of canvases remained rolled up, sealed away from the public and researchers, until the city of Denver finally won his widow’s approval.

To raise endowment funds, the city put several paintings from Still’s estate on the block, going against the artist’s wish that none should ever be sold. Legal battles ensued, but the auction was allowed to proceed; one painting sold for $61.7 million. The sale brought in more than $100 million.

The artist’s market has since been erratic, in part because so few significant works are in circulation. Those that do circulate are not always in line with contemporary tastes. PH-916, a six-foot-tall painting that carried a high estimate of $20 million, failed to sell at Christie’s last year.

The tension between Still’s art and the art world is one of the main themes of Lifeline. A pioneer of abstract expressionism, along with Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Newman, Still split from most of his peers, his gallery, and then New York altogether. He spent the last two decades of his life in rural Maryland.

“He had to get away from what he called ‘the corruption of the art world,’” says his daughter, Sandra Still Campbell.

The title of the film refers to the word Still used to describe the bands of color that snaked up and down his monumental canvases. Still’s backstory for the term, though, is less poetic.

“I asked him one time, ‘What is this thing about a lifeline?’” says Henry Hopkins, the former director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

The artist told Hopkins that when he was a young boy, his father farmed “on very bad land up in Canada.” One day, Still’s father dropped him down a new 30-foot-deep well, head first, to check if the water was reached. Still was held by a rope tied around his ankle.

“And he said, ‘It was such a traumatic experience, it remained with me all of my life,’” recalls Hopkins (who died in 2009), in archival footage.

Still wanted to exercise total control over his works inside and outside of the studio. Museum directors recount how he drove them crazy installing exhibitions, including a sprawling solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art shortly before his death.

He could also be ruthless. On a rainy day in 1958, Still walked into a home of Alfonso Ossorio, a wealthy artist and collector, who was planning to send a Still painting overseas against the artist’s wishes. Still found the painting, pulled out a knife, and cut out a piece in the middle of the canvas.

“He did refer to it as “I cut the heart of the painting out,’” says his daughter.

The cutout now resides at the Clyfford Still museum in Denver, along with the artist’s archive, about 830 paintings, and more than 2,300 works on paper and sculpture. The museum holds approximately 95% of Still’s total output. “He knew that at some point the world would come to him,” says Scholl, the film’s director. “And, of course, it did.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Tarmy at jtarmy@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.