It’s a Great Time to Be a Fancy Pork Farmer

America’s import duties have put it in a ham glut, and this is the best time to be a pig farmer in the U.S.

(Bloomberg) -- In a trade war, it pays to be off the grid.

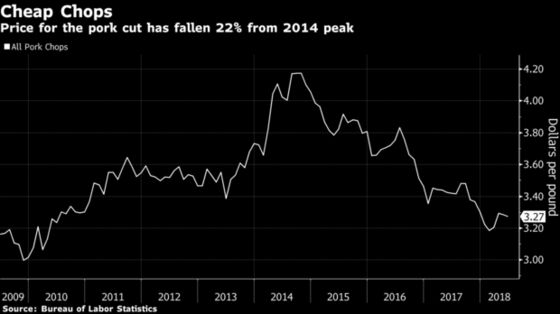

Farmers have been on the front lines of Donald Trump’s tariff standoffs. Hog prices have tumbled in recent weeks as the U.S. production outlook swells while retaliatory tariffs from Mexico and China—countries that represent 40 percent of total pork exports—have left Americans with a ham glut.

In an emailed statement on July 6, the National Pork Producers Council said, “We now face large financial losses and contraction because of escalating trade disputes.” Even after thanking the president for the planned $12 billion aid package announced this week, National Pork Producer Council President Jim Heimerl stressed in his statement the industry’s “valuable international trading relationships” that have added $53.47 to the average price, $147, that producers pocketed for each hog sold last year.

Not all pork farmers are so worried about their bottom lines. Farmers raising speciality hogs such as organic, Certified Humane, and heritage say their loyal customers won’t be swayed—yet—by cheaper competitors. They

don’t expect their prices to drop much, if at all, along with those of the commodity suppliers.

“People buy my pork because they’ve done the research, formed opinions on animal welfare, regenerative practices, and strengthening the rural economy,” says Will Harris of White Oak Pastures, a Georgia farm with seals of approval from Global Animal Partnership and Certified Humane.

His hogs are raised in the woods—eating what they forage, supplemented with peanuts and pastured eggs—and they command a significant premium. While consumers can buy 12 ounces of Oscar Mayer bacon for $7.99 at Amazon.com, Harris’s Iberico bacon goes for $31.99 a pound on his website. “There will be a lot of resilience in continuing to support products like ours.”

Commodity farmers see it as well: Going upmarket might act as a hedge.

Since the trade disputes began, Niman Ranch and Applegate, industry leadersof higher welfare pork and subsidiaries of Perdue Farms Inc. and Hormel Foods Corp., respectively, have both reported an increase in interest from farmers that want to supply them. Signing up is not easy.

“Typically, not one farm that calls us is in full compliance,” says Matt Hackfort, senior director of raw supply at Applegate. “There’s a high percentage of fallout because of the drastic changes that are needed” to meet their husbandry standards.

Consumer Loyalty

“We’re blessed with a customer base that is either so food-centric that Niman is still in their acceptable range, or so values-based [they] go out of their way to get a product that lines up with their belief system,” says Jeff Tripician, general manager at Niman Ranch, which mostly sells domestically; a 12-oz. pack of Niman Ranch pork sausage sells for almost twice as much as a comparable product from Hillshire Farms Naturals. “Values-based [customers] go out of their way to get a product that lines up with their belief system.”

Niman’s Certified Humane pork products come from a network of farms required, for example, to provide their hogs with pasture or bedding that allows them “to play, forage, explore, root, and chew.” Unlike many hog farmers, these additional restrictions come with long-term contracts that aren’t based on the commodity market, providing short-term shelter from tariffs.

“Today, our farmers are sitting there, breathing a sigh of relief,” Tripician says.

Applegate’s Hackfort says the company is used to selling a higher-priced product, and consumers are used to buying it: “These tariffs, it’s another addition that’s going to increase the delta, but the delta is the delta because of the differentiation of how we produce animals, which is much bigger than the impact the tariffs are going to have.”

“Our target customer is the one who is looking to buy for quality, not on price,” echoes David Kemp, chief executive of Les Trois Petits Cochons, maker of organic and heritage pâtés, mousses, terrines, and charcuteries.

Long-Term Effects

Stuart Blankenhorn, director of category management for Blue Apron, the meal kit company whose pork comes from hogs raised in group housing instead of gestation crates, characterizes demand for premium products as “pretty inelastic.” The company hasn’t yet seen any change in prices from pork suppliers, but if the price drop continues for six to 12 months, “expect an impact,” he says.

Customer loyalty, in order words, is finite in the face of cratering prices.

For the first signs, look to the restaurant industry, which is always looking to widen its razor-thin margins. Data from BlueCart, an online hospitality industry marketplace, shows that at least some of the food-service buyers that was ordering premium pork appear to be switching to commodity sources. While last month, 79 percent of its pork sales were for premium products, only 64 percent were from July 1 to 18. That’s also significantly lower than the 87 percent the database facilitated in July last year.

“The notion that people don’t care about better food has been overcome. They do,” says David Barber, co-owner of fine dining restaurant Blue Hill and founder of Almanac Insights, a BlueCart backer. “But there is a price-premium tolerance that directly affects decisions for many. When the gap is too wide, customers will opt for cheaper and less sustainable alternatives.”

Greg Gunthorp, who raises Duroc pigs on pasture, from “farrow to finish,” in LaGrange, Ind., agrees: “The level of commitment of buyers will shrink as the commodity price drops to next to nothing. It’s just too much of a premium.”

Yet, for now, high-end producers are holding firm, prepared for any dip in consumption.

“There is a huge cost to raising heritage pork, truly free-range,” says Ariane Daguin, founder and chief executive officer of high-end meat distributor D’Artagnan Inc. Her consumer prices are, like her contracts with farmers, based on such costs of production as breeding, outdoor space, labor, and feed. “We’re not going to compromise,” she says.

This suits farmers such as White Oak’s Harris just fine. “Our goal is to sell the production we make on our family farm,” he says. “We don’t want to run a huge multinational corporation. My goal is not unbridled growth.”

--With assistance from Megan Durisin.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.