Interscope at 30: A Chat With the Heads of the World’s Biggest Record Label

Interscope at 30: A Chat With the Heads of the World’s Biggest Record Label

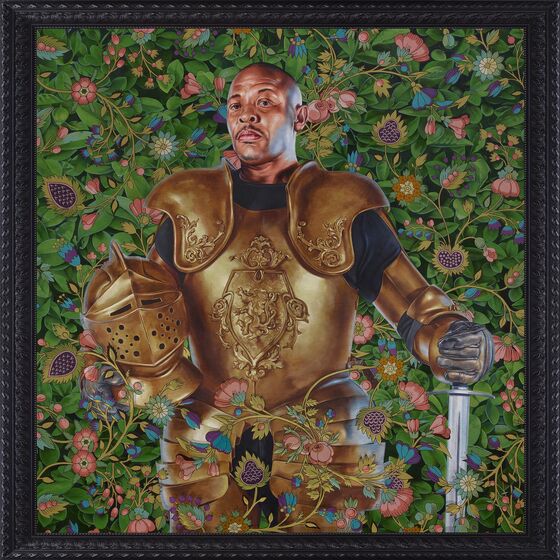

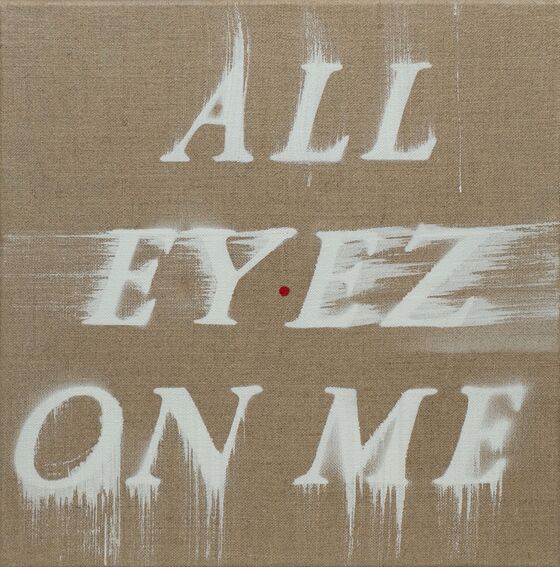

(Bloomberg) -- Later this month, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art will mount an exhibit showcasing some of the most famous contemporary artists, including Ed Ruscha and Kehinde Wiley. All 51 pieces were inspired by albums or songs released by Interscope Records.

Founded in 1991 by Jimmy Iovine and Ted Field, Interscope is one of the most influential labels of the last three decades, home to seminal hip-hop albums from Snoop Dogg, Kendrick Lamar and Eminem, rock from U2 and Nine Inch Nails, and pop smashes from Lady Gaga and Billie Eilish.

Iovine, 68, got the idea for an art show from Justin Lubliner, who works with Eilish. He took the idea to John Janick, 43, Interscope’s current chief, who enlisted a team that included Grammy-nominated producer Josh Abraham. Both Iovine and Janick are avid art collectors, and used their network to commemorate the label’s 30th anniversary.

Ruscha was the first artist to step forward, volunteering to paint Tupac Shakur’s “All Eyez On Me.” Raymond Pettibon painted Lana Del Rey’s “Norman F---ing Rockwell!” Wiley rendered Dr. Dre’s “2001,” and Damien Hirst crafted a piece showcasing 12 Eminem albums. Interscope will also sell small-batch, special-edition vinyls of 57 albums, featuring cover art from the show. Most of the money will go to a school founded by Iovine and his longtime business partner, Dr. Dre.

“This project shouldn’t have happened, to be practical. It’s just too hard,” Iovine said. “These artists are all working. They had to stop what they were doing. It’s like walking over to a great musical artist and saying, ‘Would you stop your album to do this’?”

Iovine stepped away from Interscope in 2014, and handed the baton to Janick, who has since turned Eilish and Olivia Rodrigo into two of the world’s biggest pop stars. Interscope was the biggest record label in the U.S. last year, responsible for more than 10% of all sales.

Interscope’s two chiefs gathered on a balmy Sunday afternoon at Iovine’s compound in Malibu, California, to talk with Bloomberg News about the project, along with the past, present and future of Interscope. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

When did you start having conversations with the artists about this project?

Janick: It was early last year. It’s been less than a year, which is crazy that we’ve been able to pull that off.

Iovine: Maybe you could have said, “Why don’t you cure cancer?” I mean to go get all these artists that paint the covers. A little bit of execution is gonna be involved with that, which is very, very difficult.

When did you start collecting art?

Iovine: Nine years ago when I met my wife. All my friends collected, but I didn’t start collecting until I was out of Interscope. I never crossed the two. I was just all about building those things; I never really had any hobbies. My wife is really into it. And David Geffen is always telling me to collect art.

What I used to get from music was that sort of anarchy, socially conscious kind of music. I really got off on that, because when I was a kid, my first three artists were John Lennon, Bruce Springsteen and Patti Smith. As we were going on, there was less and less of that in music. But I found that in art.

Janick: Signing artists is like art collecting. You find these great artists that you support and that you want to help in any way you can.

Do you share Jimmy’s sentiment that music now feels less political?

Janick: Interscope has always been the place with artists that have a very strong point of view. Kendrick, you listen to anything he does, and there is no one else like him. Billie too.

Iovine: I just wish there was more of it. I know it’s out there and maybe I’m not hearing it. It’s one of the reasons I subconsciously left the music business, other than the fact that I wanted to go to technology.

You’re doing this all on the 30th anniversary of Interscope. How would you describe the company now to someone who has no idea of what it is, and how does that compare to your initial vision?

Iovine: [Interscope parent Universal Music Group] allowed me to pick my successor. I knew I had to find an entrepreneur. I knew that somebody that was too deep inside the music business wasn’t going to work. You’ve got to find somebody who’s very, very disciplined, but also still sticks to their beliefs and is willing to fight off all the things that come at you when you’re running a label. And I also had to find a good person, because I was leaving all my friends behind.

Interscope is more and more becoming a blend of two companies—what it is today, and what it was. Most companies, when the founder leaves, they don’t do well. Because the founders were powerful cults of personality.

What did you mean when you said what it was and what it is today?

Iovine: We were running for our lives. We were a new label. When it got to be 2000, Interscope became a proper label. The 2000s were the bridge, so you could have Billie Eilish and Kendrick and the great hip-hop music. And then also Olivia Rodrigue or whatever the f--- her name is.

She’s really good. Because she’s a blend of those two worlds. She writes good lyrics. She’s a real artist. And you’ve got to try to sign real artists. When you’re running a company this size, you got to keep the wheels turning. So not everybody’s gonna be a poet.

In the 1990s, you put out five to seven records a year. In the 2000s, that goes to 10 or 12. Now?

Janick: Hundreds.

What accounts for that explosion?

Janick: There’s a mentality with a lot of artists of always being “on.” It’s so easy to communicate with your fan base, just the way the world has changed technology wise.

Iovine: Something fundamentally changed. Nobody wants to go away. How could you miss somebody if they don’t go away? Everybody wants to put out a record every hour, right? Am I wrong?

Janick: And the barriers to entry have been lowered.

Iovine: In the old days, you come off the road and take a break. Now they are on the stage, running off into a remote truck and recording the album.

Interscope has been on a pretty good run the last couple of years. To what do you attribute that?

Janick: You have to plant seeds and let things grow. When I came into the company, it was like, “What kind of music do you want to sign?” I came more from a rock-pop background. But Interscope was always amazing at finding the best artists in every genre.

How does the role of label head change when the business balloons?

Janick: You have to have the right people in the company. I want our artists to be able to come to us on anything. We’re making films with our artists. We’re helping them with their tour production. You have to protect the brand of the artists in every which way possible.

Iovine: John is a much better executive. All I ever did was exactly what I wanted to do at any given moment. It could change on a dime; it was completely impulsive. I just did whatever I felt. John’s a much better executive. I’m not an executive. I just do things.

Janick: I wish I was a little bit more impulsive. You have an amazing gut and obviously the impulsiveness works.

Most of the big decisions still have to be gut decisions?

Janick: Yeah, but Jimmy is a little bit lighter on the feet. I feel like I always have a heavy weight.

Iovine: I’m very intense. When I was working, I would focus on Interscope the way I would focus on the guitar on “Born to Run” or “Thunder Road,” like for six weeks on one guitar.

Janick: We experienced some of that on the art project.

Iovine: I’m being very good on this project.

A decade into the streaming era, what have been the most significant changes for the art and for the business?

Janick: There’s more tools. The barriers to entry were high. You had to have distribution, you had to have radio, you had to have MTV. I bought records by underground bands that I really liked from indie stores, and I’d do mail order because I grew up in a small town. Everything that I did growing up prepared me for when the internet actually happened.

You still can break an artist through radio, [but] you can break artists through streaming and getting the right playlists. You can break an artist with the right visual on YouTube, you can break an artist by doing TikTok. You can break them in another territory. “Blurred Lines” broke out of France and started to travel out of that. Gaga broke in Germany and Canada.

Iovine: Technology is really affecting the A&R process [scouting and development]. There was a day in A&R where everything was handpicked. Now it looks to me like the labels use gill nets. In the old days, you fished with a fishing pole. Now anything that moves gets signed.

Janick: He’s 100% right. We pass on 99 out of 100 things that might seem like a trend. Olivia is a perfect example. “All I Want” was a song she wrote that was in [the 2019 reboot of] “High School Musical.” I thought the song was crazy. It was great. But I’m like, I’m not signing the girl. I told her this. Then I sat with her. She has vision. She’s an amazing songwriter. She knows exactly what she wants to do.

Interscope happened at the beginning of hip hop’s rise. Do you see another genre or cultural movement as the next big wave?

Iovine: I don’t know the answer to that; John does, but I can tell you about 1990. We were hellbent on crossing that stuff over in Europe, Top 40 radio. If Interscope did anything, it helped do that. I remember when we signed Death Row and some people at Warner Music said to us, “This stuff doesn’t sell overseas, you’re paying too much money.” I said, “If you heard this record—it was ‘The Chronic’—they are going to be dancing to this stuff in China.” And they did.

Janick: Whether it’s just kids or the way culture is now, so many things blend together. Hip-hop and R&B are always going to be there. People say guitars are dead, but now you hear some rock music coming back. I don’t know if you can predict what’s going to be that next wave. But I think hip-hop and R&B will always be important.

Do young artists call you for advice?

Iovine: I try to help any young person I possibly can. Because people helped me. I talk to those kids at USC all the time, and that first day of school I give them my email. I’ve got nothing else to do. You know, it’ funny sitting here with you, I don’t have a job. I make album covers.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.