The Wrong Way to Visit Iceland

Since 2012, Iceland’s visitor numbers have been growing an average of 32 percent each year.

(Bloomberg) -- Icelanders like to joke that during the course of their adulthood they’ll have no less than seven careers—oftentimes two at once. In fact, being busy is such a part of the national identity, Icelanders’ most common greeting roughly translates to: “So, busy as always?”

For Herdis Fridriksdottir, who left a career in education to get busier working in tourism, the answer isn’t just “yes.” It’s “more than ever.”

Since 2012, Iceland’s visitor numbers have been growing an average of 32 percent each year. The country gets seven visitors for every local, with travel now contributing more than 10 percent to gross domestic product, making it Iceland’s largest economic sector. If “overtourism” has become a red flag for the global travel industry, Iceland is a prime example. Some sites are at risk of closing, or have closed, like Fjaðrárgljúfur canyon featured in a Justin Bieber music video. (Even if tourism numbers are forecast to drop by about 16 percent in 2019 after the recent bankruptcy of Wow Air.)

That is, of course, if you’re going where everyone else goes.

“People feel that all of Iceland is crowded … but that’s like saying a rock concert is fully booked when there are 50 people in the front row and no one in the back,” says Runar Karlsson, head guide for Borea Adventures, one of a handful of outfitters helping to redistribute tourist traffic to the country’s less-known corners. Rather than have his visitors bolt up in pricey Reykjavik hotels and crowd around the Golden Circle on day trips, he focuses on Iceland’s stunning Westfjords, which receives only 12 percent of the country’s peak-season tourist traffic.

So if you don’t also want to fall into what Karlsson characterizes as influencer-inspired Instagram bucket lists (Bieber, again) and the lopsided marketing of a handful of key sites, here’s how to do Iceland right.

Instead of focusing on landscapes, focus on locals

“Four years ago, Instagram had 800,000 photos with the Iceland hashtag,” says Gunnar Gunnarsson, a professional photographer who focuses on Iceland’s frigid landscapes. “Today that number is over 12 million.” He says it’s the result of cash-poor operators and freebie-seeking influencers creating an arbitrary (and sometimes destructive) echo chamber of “Insta-famous” and “must-visit” sites.

All this overlooks Iceland’s delightfully quirky culture. The people you meet here can be just as memorable as those ethereal fjords—and Fridriksdottir’s family-run business, Understand Iceland, is making a name for itself by setting up culturally immersive adventures, such as dying wool and knitting with village women.

Instead of international white-glove operators, support small businesses

Even though most white-glove travel agencies use the same inbound operators to source their “exclusive” experiences, small Icelandic tourism outfits are surprisingly high-quality and easy to reach online. The only catch is that they’re often buried under a few pages of Google search results.

Take Midgard Adventure, a mountaineering company based in the unassuming southern township of Hvolsvollur. Book its Super Jeep tour of the Icelandic outback’s hidden gorges and glaciers, and you may well end up at your guide’s house for lamb stew.

Additionally, both Local Guide and From Coast to Mountain deliver on their names, focusing on staffers’ childhood favorite sites such as the great ice caves of Vatnajokull National Park. The Wilderness Centre also tops many insiders’ lists for its unique hikes, which can culminate at one-of-a-kind accommodations such as traditional turf homes from the early 1800s.

Instead of transferring to Reykjavik, go south

Though few first-timers realize it, most flights to Iceland land in Keflavik, an hour southwest of the country’s biggest city. About that: Reykjavik is roughly the same size as Rochester, Minn. It’s charming, but skippable.

If seeing the capital is non-negotiable, cap your time there at 25 percent of your visit. Otherwise, head straight to the south coast, where you can stay in contemporary chalets, chic farmhouses, and small hotels. “Most of the tourists I see spend four, five, even six hours a day driving to and from Reykjavik to walk on the glacier at Solheimajokull or visit the lagoon at Jokulsarlon. It completely baffles me,” says Icelandic expedition leader Sigurdur Bjarni Sveinsson. Plus, when you’re based in the countryside, you don’t need to sign up for a northern lights tour—you can just look out the window.

Instead of dining in the capital, eat in the countryside

“The eastern region has really started to come into its own as a culinary destination,” says Carolyn Bain, co-author of the Lonely Planet guide to Iceland. Case in point: Kari Thorsteinsson, the chef de cuisine at Dill in Reykjavik, the first restaurant in Iceland to receive a Michelin star, is about to open a new concept in Egilsstadir that will focus on local product and wild game. The area is also home to restaurants such as Skriduklaustur and its haute twists on Icelandic home cooking, the Japanese-inspired Nord Austur, and Vallanes, which sources high-quality grains and more than 80 varieties of vegetables from its own farm.

Instead of Gullfoss, choose any other waterfall

A photo of Gullfoss, or “Gold Waterfall,” aptly positioned along the Golden Circle, is one of the snaps most tourists are compelled to tick off their bucket lists, despite the fact that there are over 10,000 chutes scattered around the country. Two worth prioritizing are the bundt cake-shaped Dynjandi in the Westfjords and Aldeyjarfoss, with its organ-pipe basalt columns; they see a fraction of Gullfoss’s tourist traffic and are just as photogenic, if not more so.

Instead of Blue Lagoon, visit the Retreat

There’s a certain Disneyland quality to Blue Lagoon, Iceland’s famous silica-rich swimming experience. An entrepreneur’s vision turned the boiling runoff from a geothermal power station into what’s now essentially an expensive, scenic bath with a swim-up bar (entrance starts at $59). It’s so popular, it’s inspired similar commodified experiences at Fontana hot springs and the (not-so-) Secret Lagoon.

If you’re dead set on checking out the main attraction, beat the crowds by booking into Iceland’s only true five-star hotel, a Brutalist enclave of graciously appointed rooms called the Retreat. Its sprawling spa offers access to a private portion of the Blue Lagoon, the restaurant has an expansive wine cellar, and its guides take guests on tailor-made outings through mossy fields and jagged beaches nearby.

Instead of planning a long layover near the airport, fly farther afield

IcelandAir’s free extended layover program has been a huge contributor to the country’s tourism growth. But short stays needn’t be kept to a tight radius of the airport—particularly now that ample domestic flights have made it easy to get to the remote northeast in just 45 minutes. Here’s the long weekend itinerary, doable either as a series of guided day trips or as a self-guided road trip.

Carve a triangle from Akureyri over to Myvatn’s bizarre collection of earthen anomalies (alien lava fields, volcanic craters, and steaming earth), then up to the adorable port village of Husavik for whale watching. If you have a pinch of extra time, tack on the verdant canyons of Asbyrgi or the waterfall at Dettifoss—Europe’s largest by volume.

Instead of the Ring Road, do the Western Loop

Iceland’s Ring Road is one of the most popular circuits for travelers, largely because it’s well-paved and forms a neat circle around most of the country’s perimeter. However, there’s a quieter and far more picturesque way to see the island in the same amount of time—at least eight days if you want to step foot outside your vehicle.

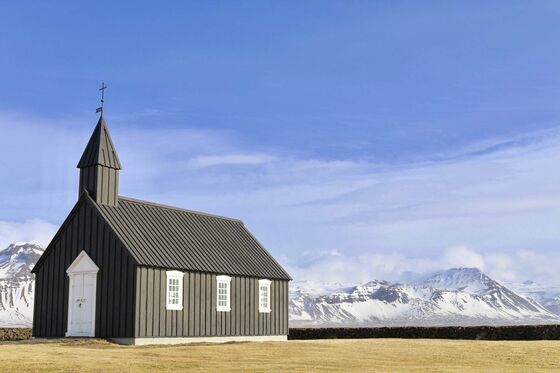

This Western Loop, as we’re dubbing it, follows the fjordlets along the western coastline up from Reykjavik, past Borgarnes, through the Snaefellsnes peninsula, across Breidafjordur’s 3,000 islands by ferry, then up into the Westfjords where dramatic, lobster claw-like outcrops snip away at the Arctic Circle. You’ll pass tiny fishing villages tucked under towering, glacially hewn mountain passes all the way to Isafjordur, where you can launch day and overnight trips into the wild Hornstrandir Reserve, home to roving arctic foxes and riotous bird colonies. Follow the craggy coast to Holmavik, where you can use a small portion of the Ring Road to close the gap back toward Reykjavik through the Golden Circle.

Conveniently, the circuit showcases some of Iceland’s best accommodations and cultural attractions, such as boutique digs in an old merchant’s home, an arctic mammal research center, and private cottages on a working ranch.

Instead of shoulder season, go in November

The most obvious way to avoid crowds anywhere is to travel during shoulder season. But in Iceland, even the tail end of summer has become swollen with booked-out hotels. This makes a strong case for visiting in the statistically quietest month: November.

Don’t shudder thinking about the weather. Iceland never promises sunshine—even in summer (it’s like that Vanessa Williams lyric, “sometimes the snow comes down in June”).

And if you’re not going to get great weather regardless, you might as well get a different perk: great lighting. Says Gunnarsson of the six or so hours the sun is up, “At the end of the year, you have a constant ‘golden hour’ glow. It’s perfect for photography.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Nikki Ekstein at nekstein@bloomberg.net, Justin Ocean

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.