How to Sell the Art Your Parents Spent Their Lives Collecting

How to Sell the Art Your Parents Spent Their Lives Collecting

(Bloomberg) -- Growing up in 1950s Long Island, Ron Irving wasn’t surrounded by wealth, or art, or high design. Still, as his father, Herbert, began to build the business that subsequently became Sysco Corp., art slowly began to make its way into the family’s life.

“They had limited means,” Irving says. “But even with those limited means they were eager to collect art. I have a vivid early memory of being bored to death being dragged to a sale in Westbury, Connecticut.”

Over time, as Herbert and his wife, Florence, became wealthier, their ambitions grew along with their ability to realize them. After a fateful trip Tokyo in 1967, the two fell in love with Asian art.

Florence enrolled in art history classes at Columbia, and the couple moved into a different house, acquired a large apartment on Park Avenue, and filled both with an unparalleled collection of Chinese, Japanese, Himalayan, and Korean objets.

Herbert died in 2016 at the age of 98; Florence died two years later. By then, the couple had already announced the bequest of nearly 1,300 Asian art objects to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, along with an $80 million donation to the museum. (Significant as that might be, the gift paled in comparison with the nearly $1 billion they gave to cancer research.)

“My sense is they wanted [their collection] to maintain its integrity and unity, and they expressed that in discussions with the Met,” Irving says. “That collection is their legacy. If it all went to an estate sale and was dispersed across the universe, it would break my heart, and I think it would break their hearts.” The gift to the Met allowed their collection to “retain its integrity,” he says. “And I think that’s enough.”

Which is to say, that’s how Irving has made peace with the estate putting the majority of the remainder of the collection, still several hundred objects, up for auction at Christie’s New York over the course of three sales. The first, an evening sale on March 20, carries a total estimate of $10.6 million to $15.6 million; the second, a day sale on March 21, contains 259 objects and carries an estimate of $4 million to $6 million; and the third, an online sale that runs March 19-26, carries a high estimate of $340,000.

“This is the nature of estate sales,” Irving says of the scenario that’s faced thousands of other boomer descendants, just, perhaps, at a slightly larger scale. “It all gets dispersed, and the lives that were led for decades get dispersed—it’s painful for any child to see the family material going everywhere, but I’m comfortable that their legacy is safe.”

How What Went Where

“Florence and Herbert were drawn to objects that were inherently interesting or beautiful or important,” says Robert Kasdin, the former chief investment officer of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, who was friends with the couple for 30 years. “They were not trying to create a collection that would be a ‘definitive collection.’ This was a bottom-up appreciation of objects.”

As a result, the Irvings’ collection was never conceived as a single inviolable entity, and acquisitions were less about “filling gaps” than they were, simply, new additions.

As the couple became more involved with the Met—Florence joined the board—“they became friends with many of the curators they worked with,” Kasdin says. As a result, “quite frequently, through conversations with a curator, they’d learn of an object the Met thought was a gap in the collection,” he says, and purchase the object. Those objects obviously made their way there.

In other instances, “a curator would come over [to their apartment] and say, ‘Oh, that’s an important object,’ ” Kasdin says. “And a couple of years later, they’d finally say, ‘OK, we’re giving the object to the Met, it’s important to the institution.’ ”

The 1,300 pieces of art the couple ultimately donated, in other words, weren’t the core of the collection, or even the best or most expensive works; instead, they were the objects that, in consultation with the museum, the Irvings determined that the museum could actually use.

“Herb grew up with literally nothing, and he felt he was the luckiest man in the world,” Kasdin says. “It’s hard to understand them if you don’t understand how smart and thoughtful and humble they were.”

What Was Left

“I would never have dreamed of saying, ‘You know, Dad, I’d like this or that,’ ” Ron Irving says. “It would have just been pointless.” Still, Florence selected several objects to leave to her children. “From her own sense of what would interest us, she gave us each a few things.” Among other objects, he was left a painting, a print of which used to hang in his apartment. “It’s my mother—I’m happy with anything she gives me.”

Hitting the auction block are several pieces that had pride of place in their apartment. Both the younger Irving and Kasdin say that the couple had special affection for a jade buffalo (estimate: $80,000 to $120,000) that sat prominently in a seating area in the apartment. “Over the years, they would talk about the beautiful curve of the back and the slight smile on the animal’s face,” Kasdin says.

Another object of particular import was a Ming dynasty jade pillow (estimate: $10,000 to $15,000) that the couple bought through the prominent dealer Alice Boney, who became a trusted adviser. “It’s a singularly special object,” Irving says. “I don’t presume that it’s special in a broader sense, but special in the narrative of the building of their collection.”

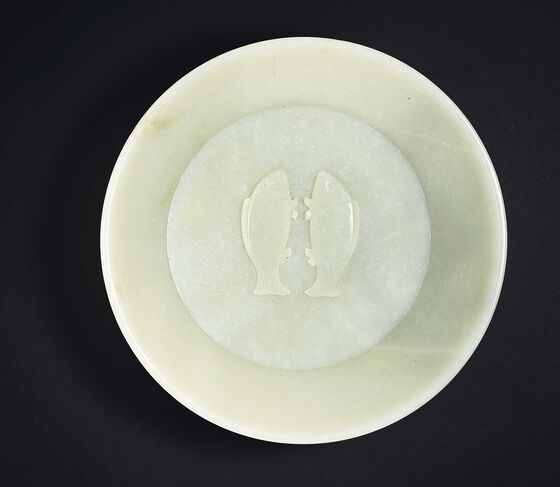

There are also some objects whose appraised value transcends sentiment. A gilt-bronze figure of Guanyin (the bodhisattva) from 11th to 12th century China is estimated to sell for $4 million to $6 million; a greenish-white, imperially inscribed Chinese jade washer from 1786 carries an estimate of $1 million to $1.5 million; and a scroll painting by the Chinese artist Wu Guanzhong carries an estimate of $750,000 to $850,000.

“Yes,” says Irving, “there’s a sense of loss, above all in losing my parents. But also in losing the objects that represent them.”

But the sale, he says, is in a certain respect a final gift from his parents. “I think they’ve done us a favor. They gave us the spirit of collecting, and the space to do that collecting on our own.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.