How Halloumi Devoured a Nation

Britain has become the world’s largest importer of a once-obscure cheese from Cyprus, but its popularity is surging elsewhere too.

(Bloomberg) -- Yiannos Pittas remembers the days decades ago when his Cypriot dairy airlifted halloumi cheese to expat diplomats in London. These days it’s flying off the shelves from Sydney to Stockholm.

But no country has embraced the rubbery cheese like the U.K., where exponential growth in demand has made halloumi the second-largest Cypriot export.

Shipments globally in 2017 rose 14 percent to 163 million euros ($185 million). That might not sound a lot, but it’s double the sales of 77.5 million just four years ago, according to the Cyprus Trade Center in London. In 1992, they were the equivalent of 2.4 million euros.

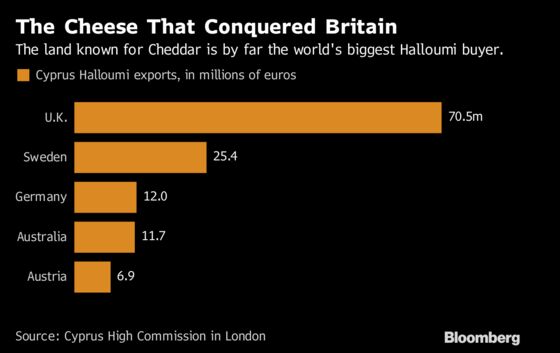

Last year the U.K. was the world’s largest halloumi importer, taking 43 percent of the shipments from Cyprus, almost three times larger than the No. 2 market, Sweden. Britons buy five times more halloumi than Germans, the third-biggest importer.

“We’ve been sending halloumi to the U.K. for decades, but it was just a couple of deliveries a week,” said Pittas of Nicosia-based Pittas Dairy Industries Ltd., one of the island’s main producers. “It is a huge business now.” Restaurant groups he has supplied include the grilled-chicken chain Nando’s.

Pittas traces the seeds of success back to the early 1980s, when Sainsbury supermarkets decided to stock halloumi in a single store on Cromwell Road in London to serve Middle Eastern customers. It started selling well, and other retailers took note.

Nowadays, Sainsbury alone has six halloumi lines, including burger slices, and plans for more. Sales have risen 18 percent in the past year and surged 62 percent in a month during this summer’s heatwave, sparking newspaper headlines of national panic over halloumi shortages (there weren’t). They are up 26 percent so far this year at rival Waitrose. By contrast, sales of Britain’s favorite cheese, cheddar, rose 3.2 percent last year.

Halloumi has a high melting point, which makes it ideal for grilling. That’s because no acid or acid-producing bacteria are used in making it, according to culturecheesemag.com, which says it’s the acid that breaks down the protein structure. Mexican queso blanco, Italian ricotta, most fresh goat cheeses, and most vegetarian cheeses act in a similar way.

Even celebrities and gourmet chefs including Jamie Oliver and Gordon Ramsay are among the halloumi fans.

“Halloumi is perfect for veggie BBQs with all its salty, squeaky deliciousness,” Oliver says on his website, which features seven dishes.

And it’s gaining not just in the U.K. Halloumi shows up on the menus in New York, for example, at fashionable joints such as Jack’s Wife Freda. Its popularity is also benefiting across the Atlantic thanks to promotion by Trader Joe’s.

There’s just one problem. People don’t all agree on what goes into halloumi, or even on where it’s made.

Historically, the cheese is made with sheep and goat’s milk, though in recent years cheaper cow’s milk has been thrown into the mix, which can now be as much as 80 percent. The government of Cyprus has taken out trademarks around the world, but a July 2014 application to the European Commission for Protected Designation of Origin status hasn’t yet been granted.

That would put Halloumi alongside other European cheeses such as Parmigiano Reggiano and roquefort, which can only be produced in particular geographic areas. As it is, some overseas producers keep using the halloumi name in defiance of Cypriot objections.

High Weald Dairy, in the south of England, advertises Organic Halloumi, Halloumi Cheese Salad and Curried Halloumi Pasties on its website and has no plans to change that.

“They’ve tried to stop us, and lot of cheesemakers have renamed it, but we have been making it for over 30 years,” said Mark Hardy, the owner.

Chef Selin Kiazim is proud of her Turkish-Cypriot heritage and takes pride in serving halloumi at her London restaurants.

“It’s a really underrated cheese,” she says. “People say it’s rubbery, squeaky. But then you say the words grilled halloumi and everyone’s eyes light up.” At Oklava, it’s grilled crisp over charcoal, then drenched in olive oil, honey, lemon juice and wild oregano.

Her halloumi is actually a British version from Kupros Dairy in north London, and it is called Anglum.

It’s inspired by the dairy owner’s grandmother, who made cheese and bread for a living in the village of Akanthou, Cyprus.

“I don’t call it halloumi,” owner Anthony Heard said. “Cheese has its provenance and the milk here (in England) is going to be different from in Cyprus. The irony is that ours is a very traditional cheese, unlike much of the halloumi that is exported from Cyprus. That has a rubbery texture and not much flavor. They call it squeaky chewing-gum cheese.”

Richard Vines is the chief food critic at Bloomberg. Follow him on Twitter @richardvines and Instagram @richard.vines.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Timothy Coulter "Tim" at tcoulter@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.