Facing Insecurity, Frieze Dealers Play It Safe

Gone, dealers say, are the days when collectors would take a chance on a six-figure work by an artist they’d never heard of.

(Bloomberg) -- Art dealers and art museums have always had a symbiotic relationship. Dealers lend work to museums, and when museums display that work, its value has the tendency to go up. (Or, at the very least, it’s more likely to go up than an artwork that’s never been exhibited.)

In the context of an art fair such as Frieze, which takes place in two separate tents in London’s Regent’s Park through Oct. 7, that commercial/institutional relationship has been on prominent display for years.

“If there’s a museum show on, or a museum show about to happen, dealers will bring that artist’s work,” says Wendy Olsoff, the co-founder of the New York gallery P.P.O.W. This year, though, there seems to be a surge of direct-from-museum art in the tent at Frieze London, which contains newer art, and to a lesser extent at Frieze Masters, where dealers tend to show more historic objects.

Olsoff’s booth at the Frieze London has two photographs for sale by David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992). Not coincidentally, a massive show at the Whitney Museum in New York, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake At Night, closed last week. “If your artist is having a major retrospective, it wouldn’t be a good choice to not bring them just when they’re at their highest level of recognition,” she says.

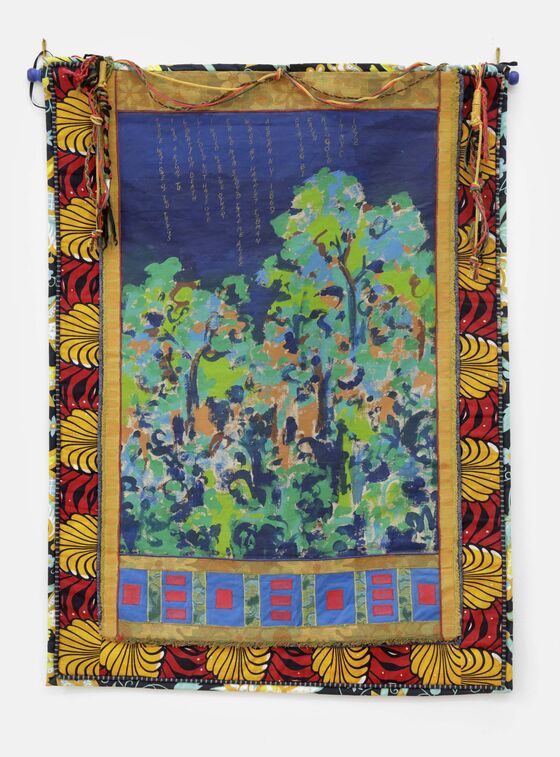

And so, among the usual art-fair material at Frieze (and let’s be clear: Anyone hoping to buy a colorful abstract painting for their living room still has plenty to choose among), visitors can find work by artists they’d seen in museums just days before. There are two works by Anthea Hamilton, who currently has a commission on view at the Tate Britain, in Thomas Dane Gallery’s booth and Levy Gorvy Gallery has a presentation of work by Francois Morellet, whose show at Dia:Chelsea closed earlier this summer. Dorian Bergen, the president of the ACA Galleries in New York, estimates that artist Faith Ringgold is currently included in 20 museum exhibitions around the world; Ringgold is the solo subject of a booth at Frieze shared by ACA and the gallery Weiss Berlin.

“We’ve been in the trenches a long time with her,” says Bergen of Ringgold. “There have been moments of great success. We’ve just been riding the wave, wherever it takes us.” That present wave is rising, she hastens to add. Prices for Ringgold’s work in the booth ranged from $160,000 for smaller tapestries to $300,000 for larger ones.

Market Forces

There are multiple theories for this rise of museum-affiliated art. One is that an institutional imprimatur is increasingly necessary to sell art at a certain price point.

Gone, dealers say, are the days when collectors would take a chance on a six-figure work by an artist they’d never heard of.

“Insecurity has come into the middle market, and that market’s impulsive buyer has dropped out,” Olsoff says. Affiliating an artist’s work with a museum show is therefore “something you can say that would give a maybe-nervous collector a little security,” she says. “Because you’re asking real money for things—you can’t forget that, no matter how wealthy someone is.”

Along with the Wojnarowicz photos (priced at $60,000 and $75,000), Olsoff is showing work by Elijah Burgher, a young Berlin-based artist who will be included in a three-person show at New York’s Drawing Center that opens on Oct. 12.

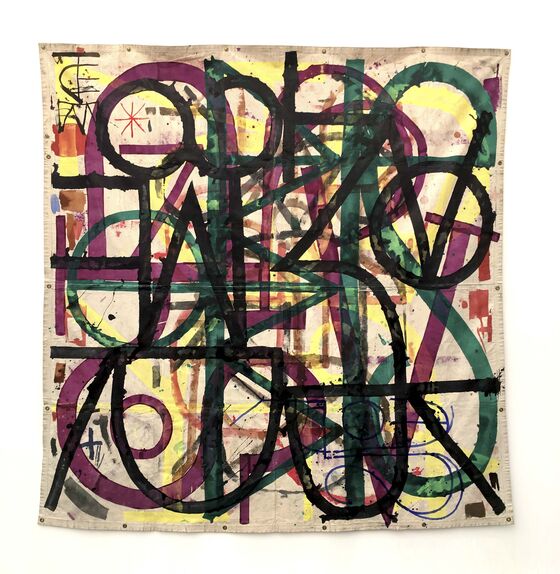

“People say, ‘Oh, the Drawing Center, that’s a great platform,’ and it gives me a bit more authority than if I just went to his studio,” Olsoff says. A large painting on unstretched canvas by Burgher is on sale for $15,000; a pencil drawing on paper, which Olsoff says is a companion to the canvas work, is listed at $10,000.

Material Over Matter

Oliver Newton, co-founder of the New York gallery 47 Canal, has a booth composed of photographs by the artist Elle Pérez, priced in the range of $5,000 to $10,000. Perez was the subject of a solo show at MoMA PS1 in New York that closed last month. “We proposed bringing their work before the PS1 show happened,” he says. “But obviously, anything that has museum provenance lends a certain cachet to the work.”

Newton, for his part, says that which works make it to fairs really comes down to what the artworks are actually made of. “We work with artists, and when they do museum installations, sometimes museums allow them to do work that requires more maintenance and upkeep and oversight,” he says. “But when you’re dealing with photography or painting or even archival-based sculpture, I don’t think there’s a lot of difficulty in that shift” from museum shows to an art fair booth.

No Golden Ticket

Some dealers caution that museum shows aren’t always a golden ticket. “It’s not that easy,” says Daniel Buchholz, whose namesake gallery has a booth featuring a massive 1992 painting by Jutta Koether on sale for $220,000. Koether currently has a major retrospective on view at the Museum Brandhorst in Munich, which will then travel to the Mudam in Luxembourg.

“To be honest, people—especially museums—say, ‘Give us some money [to help with an exhibition], and it’s also good for you.’ And yes, it’s good because it’s good for the artist,” Buchholz continues. “But it’s not a one-to-one thing, where someone has a show at the Guggenheim and we sell 10 times more art. It doesn’t work like that.” Still, he acknowledges, “in the long term, it helps.”

Ultimately, the works on view at Frieze—or any art fair, for that matter—have as much to do with a gallery’s needs as with collectors’ taste.

“If you do enough of these fairs and have so much staff and complications, you’re spending a lot of money,” says Olsoff. “You don’t want to go into this and not have your best opportunity to make money. It’s a business. But you try to tie it in to reflect our program on the deepest level.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.