Chinese Art’s Final Frontier Might Be New York

Chinese Art’s Final Frontier Might Be New York

(Bloomberg) -- Like many liberal arts graduates before him, in the mid 1990s, Gang Zhao found himself, with some reservations, working in finance. “I was an artist, I didn’t study economics,” says Zhao, who was born in China, studied painting in Maastricht, the Netherlands, and then got a B.A. from Vassar College.

After a few years working as an artist in New York, he needed to pay the bills, so Zhao made the switch. He was hired by a now-defunct boutique firm on 56th Street, working on mergers and acquisitions and initial public offering advisory projects. Once he had made enough money, he enrolled in an MFA program at Bard College.

As an artist, “I always managed to sell a few paintings” to international collectors, he says. “But not so much.” In the early 2000s, he moved back to China, where he developed a successful art practice.

Fifteen years later, Zhao is returning to the New York market with a solo show running from March 15 to April 19 at Greene Naftali Gallery in Chelsea.

In the interim, global demand for Chinese contemporary art has grown dramatically. Last September, the work Juin-Octobre 1985 by Zao-Wou-ki sold for a record-setting $65.2 million at Sotheby’s in Hong Kong, while the overall Chinese art market accounted for 19 percent of global art sales in 2018, according to a UBS/Art Basel art market report.

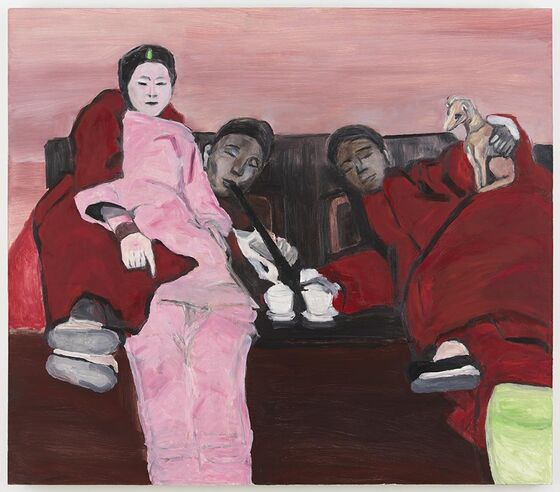

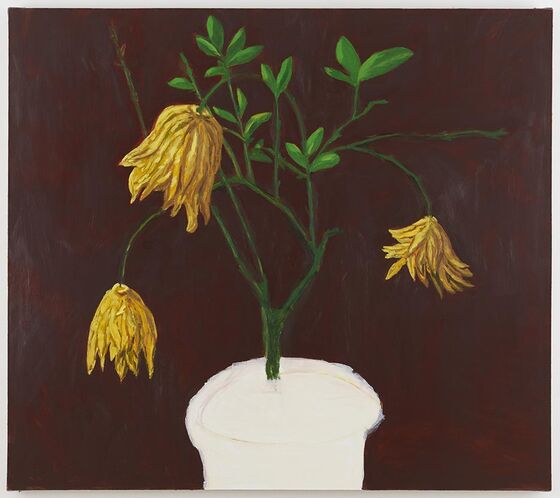

Even so, Zhao, whose rich, figurative paintings depict “court figures, leisure scenes, social decadence, political propaganda, and landscapes,” is opening his New York show in an uncertain market.

“Chinese contemporary art is really collected by China,” says Larry Warsh, the publisher of Jing Daily and a collector whose Chinese art includes work by Ai Weiwei. “The activity from western collectors was 10 to 15 years ago, and people who bought [Chinese] art then really thought China was going to explode.”

It did, Warsh says, “and a lot of people did well, but the point is that I don’t believe the actual collecting base is here [in New York]. Museums collect, and selected global collectors will want Chinese art, but the real action is in China.”

An Unequal Exchange

That, dealers say, is the real issue: Since the 1990s, a handful of Chinese artists have had global success. A work by Cui Ruzhuo sold for $39.6 million at Poly Auction in Hong Kong in 2016; the 2001 painting The Last Supper by Zeng Fanzhi sold for $23.3 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in 2013; Ai Weiwei’s 12 Zodiac heads sold for £3.4 million pounds ($4.5 million) at Phillips in London in 2015.

But even as Western galleries attempt to break into this lucrative Chinese market—recently, David Zwirner, Hauser and Wirth, Levy Gorvy, and Gagosian have joined early players such as Pace in opening outposts in China and Hong Kong—there hasn’t been an equal exchange.

“You have to remember that the historical situation is completely different,” says John Tancock, a historian and advisor to Chambers Fine Art, a gallery that pioneered the market for contemporary Chinese artists in both New York and Beijing.

“China was just opening up to the West, the economy was booming, and a handful of artists started producing work that was of tremendous appeal to Western collectors.”

Today, Tancock continues, “that is no longer the case, and there’s no longer quite the interest in China as a sort of unknown phenomenon.”

There are obvious exceptions. Ai Weiwei is the major one; Liu Ye, whose work has sold for more than $5 million at auction, was just picked up by David Zwirner; Zhang Huan, who’s nine-photograph piece Family Tree (edition of eight) sold for $640,000 at Christie’s Hong Kong in 2014, is represented by Pace; and several others have a robust international collector base.

But those artists came of age in the 1990s, more than 20 years ago. Their followers have been less successful, at least in the U.S. “I think to a degree what has happened is the same as with contemporary Japanese art,” says Tancock. “Certain artists have become international favorites—but only a handful.”

Welcoming Market

Yet there’s reason to believe that Zhao, whose prices at the Greene Naftali show range from around $34,000 to $76,000, could be welcomed.

Tancock cites two recent Chinese artists that Chambers introduced to the U.S. who’ve been met with success—Taca Sui and Yan Shanchun. More important, Zhao isn’t a total unknown. He already has some collectors in New York, thanks to a 2016 show with Tilton Gallery, and unlike some of his peers, Zhao is working in an established vernacular.

“He has all the touchstones of an international artist,” says Greene Naftali co-founder Carol Greene, referencing Zhao’s education in the Netherlands and New York, his affinity for artists such as Luc Tuymans, and his existing aesthetic. “The work is so deeply historically informed, but it’s so contemporary in dealing with social issues. He’s painting in a disruptive tradition.”

When she considers an artist for her gallery, she continues, “I approach representation based on how I see them fitting into an international dialogue. To me, it’s super-exciting to find a Chinese painter who can potentially make the crossover.”

For his part, Zhao says he’s not concerned. “I think I’m OK,” he says. “In the beginning, people didn’t really understand my art. Now it’s shifting in my favor.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Justin Ocean at jocean1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.