Cartier’s Hidden Debt to Islamic Art Unearthed in New Exhibition

Cartier’s Hidden Debt to Islamic Art Unearthed in New Exhibition

(Bloomberg) -- The Louvre’s acquisition of two exquisite, ivory pen boxes in 2018 has sparked an entire exhibition on the hidden connections between the house of Cartier and the world of Islamic art.

Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity will run through Feb. 20 at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD) in Paris, and then will travel to the Dallas Museum of Art, where it will be on view from May 14 to Sept. 18, 2022.

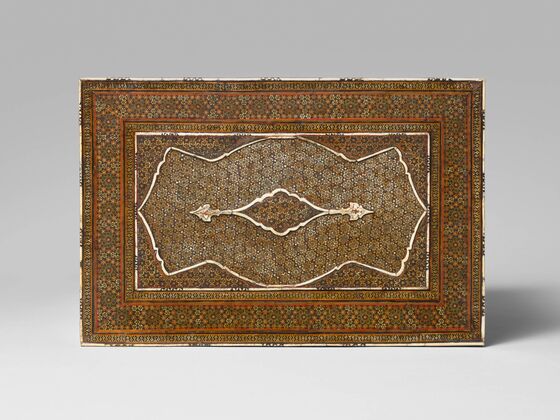

The two boxes, originally made for the court of Shah Abbas (1587-1629), the ruler of present-day Iran, had made their way into the collection of Louis Cartier by 1912.

Cartier, part of the third generation of brothers who turned the family company into an international brand, was something of an aesthete. Wealthy himself by virtue of two advantageous marriages, he assembled a vast collection of manuscripts, artworks, and objets that were eventually sold by his heirs.

In researching the provenance of the pen cases, “I realized that no one knew about his personal collection of Islamic art,” says Judith Henon-Raynaud, deputy director of the Louvre’s Department of Islamic Art, who co-curated the show at the MAD.

Henon-Raynaud realized she could use the cases as a jumping-off point—not simply to illustrate Cartier’s nascent Orientalism, she says, but to demonstrate the “importance—and impact—of the discovery of Islamic art on Western artists at the beginning of the 20th century.”

It’s a piece of design history, she continues “that has been lost with time, and Islamic art was the departure point for some masterpieces in decorative art and jewelry.”

Growing Influence

Western Europe has been engaged in dialogue with Islamic art for a millennium, but it wasn’t until the early 20th century, Henon-Raynaud says, that Islamic art began to be recognized as containing masterworks, rather than pieces of exotica.

“There was a big exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 1903, which is really the beginning of when you can see a scientific organization and historical classification of Islamic art,” she says. “And then there’s a big exhibition in Munich in 1910 about Mohammed and art, and it marks a major transition in Orientalism, because it’s about the objects for the objects’ sake.”

Part of this shift was simply a consequence of increased globalism; a further factor was Iran’s constitutional revolution in 1906.

“That allowed many paintings and manuscripts to leave the country— pieces from the royal collection of very, very high quality, which people had never seen before,” says Henon-Raynaud. “And this created a very passionate fashion for it in Paris and Europe.”

Making Connections

Cartier’s interest in Islamic art, in other words, was part of a much broader zeitgeist.

And so it was up to Henon-Raynaud, together with Évelyne Possémé, chief curator of ancient and modern jewelry at the MAD, and Dallas Museum of Art curators Heather Ecker and Sarah Schleuning, to demonstrate how this zeitgeist translated into Cartier’s famous jewelry.

“First we chose the jewelry from the Cartier collection that seemed to have elements of motifs coming from Islamic art,” says Possémé. “And after, we tried to find a link with the archives and drawings from Cartier’s original collection.

This was facilitated by Cartier, the company, which today is owned by the luxury goods conglomerate Richemont. (Cartier, not coincidentally, is the show’s sponsor.) The company opened its Geneva archives to the curators, who pored over material in an attempt to find indisputable connections.

Direct Inspiration

The result is a show of more than 500 pieces of art, showcased in an exhibition design by the architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

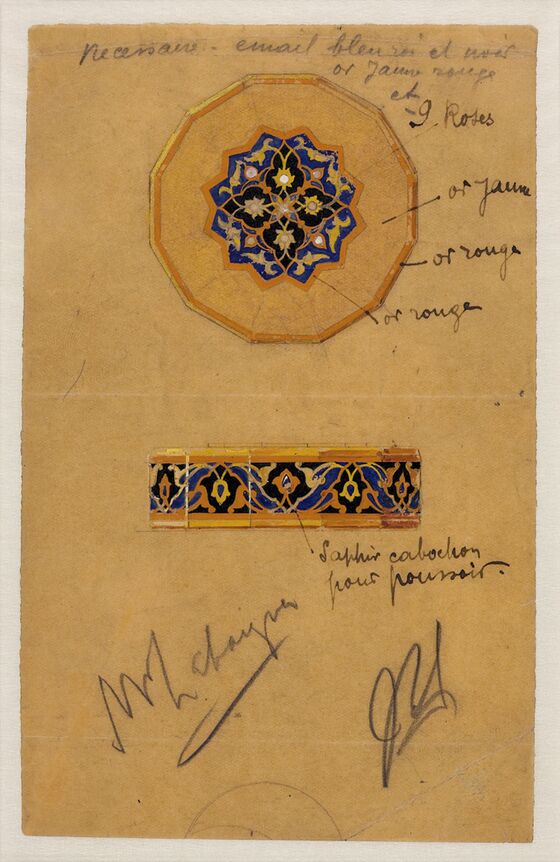

Some of the connections are clear-cut. “Take an Iranian casket with a very specific design,” says Henon-Raynaud. “We were able to find a rubbing he took of its medallion, and then we found a few drawings where he tried to translate it to a vanity case.”

The original box and the vanity case feature in the exhibition.

Similarly, the pen boxes that sparked the exhibition have straightforward aesthetic parallels; drawings by Charles Jacqueau, a principle designer at Maison Cartier, include motifs from the boxes, and a 1925 gold vanity case in the show, decorated with rubies, diamonds, pearly, onyx, and enamel, contains a similar decoration.

Yet another nearly direct copy is a late 14th to early 15th century fragment of architectural decoration; that fragment formed the basis of a powder box—the drawing of which accompanies the fragment.

Subtle Recreations

Other objects, while dazzling, have less obvious parallels.

A striking tiara made from blackened steel adorned with platinum, diamonds, and rubies is paired with an 11th century to 12th century bronze mortar.

“The link is the pear shape,” says Possémé, referring to the pear-shaped diamonds and the pear-shaped motifs on the outside of the mortar.

Elsewhere, the curators were able to find a design book in the Cartier archives by Owen Jones, who recreated patterns from the Alhambra Palace in Grenada for use in European industrial design.

We discovered that this incredible diadem [tiara] came from a plate from Jones,” says Henon-Raynaud. “It’s a complete demonstration of the original source material.”

An Evolution

By the 1930s, Cartier had begun to move away from Safavid and Persian influences and toward Mughal designs from India. (Think of its famed “Tutti Frutti” bracelet.)

But there was no specific moment in which Cartier broke with its Islamic influences, which, Henon-Raynaud says, is the point.

“When we started to organize the show, we thought about organizing the objects chronologically,” she says. “But nothing emerged—because we made the supposition that one pattern might appear at the beginning—but in fact, there’s no evolution. They used all these Islamic patterns all the time.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.