After the Blast, Beirut Fights to Save Its Architectural Heritage

The blast that ripped through Beirut caused up to $4.6 billion in damage but the city wants to save its architectural heritage.

(Bloomberg) -- It’s been two months since the blast, and Maria Hibri has glued together the splintered filigree from her triple-arched windows. In a bathroom, the broken sink stays broken, a reminder of the day her world blew apart. The folding balcony doors have been refitted or replaced with salvaged lookalikes, but they still look out of place.

Bokja, the Beirut furniture design company Hibri co-founded with Houda Baroudi in 2000, quickly repaired its studio in Basta, a neighborhood crowded with antique shops, following the massive Aug. 4 explosion at Beirut’s port. More than 190 people were killed, 6,000 injured and some 300,000 homes damaged or destroyed.

Their boutique, located in upscale Saifi Village, remains closed as the women focus on mending customers’ furniture free of charge, leveraging Bokja’s knack for refreshing dated pieces with vintage fabric and embroidery.

“I wanted to keep the anger. I didn’t want to brush it away, rebuild, reopen. I didn’t want to be resilient. I wanted us to mourn our dead, our wounded, our homes and all these places where we made our memories,” said Hibri, 56. “Then we decided to do what Bokja does best: Take what’s broken, take those old pieces and make a new whole, put something together from what’s already there, try make sense of it, give it meaning.”

The blast that ripped through Lebanon’s capital caused up to $4.6 billion in damage. Among the buildings destroyed when tons of ammonium nitrate detonated in a port hangar were some of Beirut’s last surviving historical quarters. Decimated were graceful rows of pastel-colored art deco apartment blocks nestled against Ottoman-era houses with trademark red roofs, high ceilings and dramatic windows capped with three pointed arches—Lebanon’s architectural signature.

Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael, two of the worst-hit neighborhoods, became popular with artists, designers and journalists after Lebanon’s civil war ended in 1990. Linked by rows of cafe-lined steps to grand mansions that dot the ridge above, the neighborhoods were known for their old-world charm, central location and previously affordable rents. Bars, restaurants, galleries and studios are mixed in with hardware stores, hole-in-the-wall tailors and watch-repair shops.

These streets emerged largely intact from a bloody 15-year conflict that still lends the city an air of danger. But more recently, developers eager to gentrify them have been slowly accomplishing what the war could not: the demolition of Beirut’s architectural heritage.

Now, architects and campaigners fear the blast will speed the process, as property owners who can’t afford to rebuild are forced to sell. Within days of the explosion, brokers were already circling. While the government imposed temporary restrictions that made it harder to knock down buildings and froze some property transactions, none of that helps pay for repairs.

Property owners were already in trouble before the explosion. A currency crisis and triple-digit inflation wiped out the savings of many Lebanese—and that was before the coronavirus pandemic swept in, killing 600 people and sickening 53,000 while shuttering businesses and obliterating jobs.

Gemmayzeh and Mar Mikhael are home to some 80 or so designers who have transformed the area into a hub for creative industries. In the wake of the disaster, architects, engineers and urban planners joined together to save the area’s heritage buildings. Called the Beirut Heritage Initiative, they identified about 640 damaged structures, with some 60 at risk of collapse.

By late August, the initiative—working with volunteer contractors and Lebanon’s Directorate of Antiquities—had stabilized 15 structures with scaffolding.

That was just the start. More money was needed to seal buildings from the elements, restoring and—in some cases—rebuilding them. Non-governmental organizations such as Live Love Beirut pitched in while the United Nations cultural arm, Unesco, launched an appeal for funds, estimating that $500 million will be needed over the next year.

But the heritage campaign has attracted only a fraction of that, according to architect Fadlallah Dagher, one of the initiative’s founders, whose own home, a 19th century villa in Gemmayzeh, was heavily damaged.

“When we talk about heritage, we’re not just talking about the architecture,” Dagher said. “We’re also talking about the people who live there, their memories, their interaction with their community, what gives them an attachment to these places that isn’t there with the new towers,” he said.

Dagher estimates that his own house will take months to fix. In the absence of clear laws preserving heritage, he said some residents may abandon their homes or shops altogether, irrevocably changing the area’s character.

Architect Youssef Haidar, 55, has helped renovate some of the city’s more memorable historic buildings, including Beit Beirut, a former sniper den transformed into a museum. He said the biggest obstacle to preservation is Lebanon’s dysfunctional political system. “Without real change at the political level, with the same warlords in charge of the country, we’ll find our heritage—these wonderful layers we’ve fought for three decades to save—under threat again,” Haidar said.

Like many Lebanese, Haidar left during the civil war, returning afterward to find a city exhausted, traumatized and changed. The demographics of Beirut had been reshaped as people fled sectarian killings, snipers and shelling. The downtown district near the port had become a no-man’s land, its warren of souqs abandoned to stray dogs and rats.

Postwar reconstruction was spearheaded by the late Prime Minister Rafik al-Hariri. Property was expropriated and handed to a new company, Solidere. What emerged was a sanitized downtown, its covered markets replaced by a modern shopping precinct more suited to big spenders from the oil-rich Gulf than ordinary Lebanese.

That experience has motivated today’s activists to preserve not just buildings of architectural merit, but the social and economic fabric of neighborhoods that reflect layers of migration and conflict—from Syrians fleeing their own civil war to South Asian laborers in search of work.

That’s no easy task in Lebanon. Over the years, successive governments have allowed owners to destroy landmark buildings by winking at the removal of traditional red roofs or purposeful neglect of vulnerable wood and sandstone structures.

For now, museums, cultural centers and some historic buildings have won outside financial support. Volunteer organizations and charities are working to replace windows, doors and roofs in hundreds of homes, while crowdfunding has provided much-needed support for businesses, particularly restaurants in Mar Mikhail and Gemmayzeh. But it may not be enough to ensure their survival.

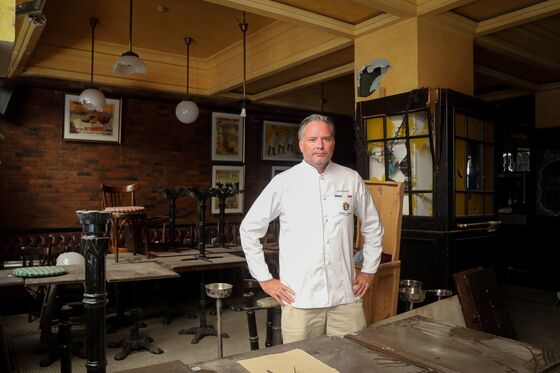

Chef Alexis Couquelet co-founded Couqley, a French bistro in Gemmayzeh, about a decade ago. Before the blast, many people had already stopped dining out because of the currency crisis and Covid-19 shutdowns, he said. With finances already stretched thin even before the added cost of damages from the explosion, Couqley will remain closed for until conditions improve.

“It’ll be a while before people are comfortable eating out in Beirut again,” said Couquelet, 48, sitting in his office, his back to a hole in the wall where balcony doors once stood. “I love this country, the people, but I hate what’s happening. The government, they’re criminals,” he said. “I want to reopen Couqley, I don’t want it taken away—but there’s only so much you can take.”

On the same cul-de-sac as Couqley sits Aaliya’s Books, a bar-bookshop that was a second home for local journalists and writers. Its managers said they are determined to return.“Ours isn’t just a business, it’s become a community, it’s a cultural center,” co-owner Naila Sab said in the weeks after the blast. “That’s why we have to reopen, because it became a gathering place for all kinds of people who’ll have nowhere else to go.”

On the hill above Gemmayzeh sits Sursock Palace. Built in 1860 by the wealthy Sursock family, it’s a prime example of the grand villas that once graced the area. Having survived successive conflicts mostly intact, it was protected for decades by Yvonne Sursock Cochrane, who belonged to a class of Middle Eastern aristocrats who once moved seamlessly between Beirut, Alexandria and the capitals of Europe. Her son, Roderick Cochrane, returned in 1996 and set about restoring the turreted mansion, a labor of love funded partly by weddings and events held in its grounds.

The port blast did more damage to the palace in a few seconds than it had suffered through its history, with repair costs likely to run into the tens of millions of dollars, he said. The roof collapsed, leaving the sky visible from the dramatic stairwell. Antique furniture collected over generations was splintered, statues decapitated and canvases slashed by flying glass. Upstairs, walls were cracked, and plaster from ornate ceilings lay in clumps on the floor below.

Yvonne Sursock Cochrane, born two years after the creation of modern Lebanon, was injured in the blast. She died on the eve of the country’s centenary on Sept. 1.

“I’m going to stay, because we have to put up some resistance to what’s going on,” her 68-year-old son said. “I can’t possibly see Lebanon disappear forever, culturally, socially—but if we all leave, that’s what’s going to happen. It would be a pity to see the character of this part of Beirut disappear altogether.”

At least help to repair furniture and paintings at Sursock arrived from day one. The Directorate of Antiquities offered scaffolding to stabilize the structure, and metal sheeting was promised to seal the roof.

Across the road from the palace is the Sursock Museum, also damaged in the explosion.

The white Italianate villa, which opened to the public in 1961, was later extensively renovated and expanded, reopening in 2015 as Lebanon’s foremost arts center. The blast blew out its stained glass windows, knocked down doors, false ceilings and walls, covering everything with gray dust. Initial estimates suggest repairs could cost more than $3 million.

On the day of the blast, director Zeina Arida was working in the windowless, air-conditioned office of a colleague, escaping injury when a huge window crashed into her own office. Arida and her colleagues picked their way out into the courtyard, where they saw a bride who had been caught in a photo shoot, sitting in a white grown on a bench amid the rubble.

More than twenty-five pieces of art were damaged, Arida said, but coronavirus closures had meant there wasn’t much on display. Almost immediately, international support came from the British Museum, the Tate, the Pompidou Center, MoMA and other art foundations. Aliph, a Swiss organization dedicated to saving heritage in conflict zones, put forward $5 million toward safeguarding Beirut heritage buildings and has offered to waterproof and stabilize the museum.

Arida hopes to fully reopen in a little over a year, to coincide with the museum’s 60th anniversary.

“We’ll rebuild. I’m not worried about Sursock Museum, but it’s not just about us—it’s about the survival of the whole cultural ecosystem that was already underfunded,” she said. “What happens to our artists? Without them, we’re just a building.”

It’s a question that preoccupies Joumana Asseily, whose contemporary art gallery Marfa (Arabic for port) is just 400 meters from ground zero, tucked away on a side street among shipping agents and customs offices. Asseily fled Lebanon with her family at the age of nine, leaving by boat to Cyprus and on to Paris and later, the U.S. She returned only months before the 2006 war with Israel.

“The location was important to me. I loved the idea of being at the port—the entrance of Beirut, this place where everything arrives and from where it all departs—our connection to the world,” she said. Though built in 1948, the building is unremarkable, a gallery space made up of two garages. “We started getting people who work in the port, our neighbors, dropping by to look at the art, people who’d never visited a gallery before.”

The gallery remains standing despite its proximity to the Aug. 4 blast. Asseily said she’s determined to reopen by next year—for the artists, if nothing else. For now, she’s been offered temporary exhibition space by two galleries in Paris.

As for Hibri, Bokja’s online sales have managed to keep her artisans employed. She’s optimistic that her city, famous for its seductive beauty and perpetual suffering, can flourish again.

“Some of their friends just want to leave,” she said. “But for the first time, there are those who say, ‘We’re staying,’ and this is what makes me want to fix my house.” A home, Hibri said, that is “nearly perfect again. Perfect in its imperfection.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.