Why Indonesia Is Shifting Its Capital From Jakarta

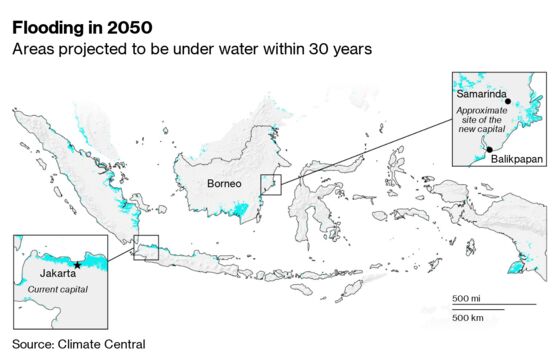

Two-fifths of Jakarta lies below sea level and parts are dropping at a rate of 20 centimeters (8 inches) a year.

(Bloomberg) -- Jakarta is soon to become an ex-capital city. Indonesia is planning to move its administrative headquarters from its richest island of Java to the forest island of Borneo. President Joko Widodo is betting that a new capital for the Southeast Asian nation will better spread the wealth among its 267 million citizens -- and ease the pressure on overcrowded Jakarta, Indonesia’s commercial and political hub for centuries.

1. What’s wrong with Jakarta?

As well as bursting at its seams, the city is sinking. Two-fifths of Jakarta lies below sea level and parts are dropping at a rate of 20 centimeters (8 inches) a year. That’s mostly down to the constant drawing up of well water from its swampy foundations. The concrete and asphalt carpet that accompanied urban sprawl prevents heavy rains from replenishing the aquifer. Instead, neighborhoods frequently flood; at least 60 people died in January. Stultifying traffic congestion and polluted air are a daily reality for Jakarta’s 10 million inhabitants. The gridlock costs an estimated 100 trillion rupiah ($7 billion) a year in lost productivity for the greater Jakarta area, known as Jabodetabek, encompassing 30 million people.

2. Where will the new capital be?

An area straddling two regencies, North Penajam Paser and Kutai Kartanegara, in East Kalimantan province. (A new name has yet to be chosen.) Kalimantan is the Indonesian part of Borneo island, which is also home to two Malaysian states (Sarawak and Sabah) and the nation of Brunei. Some 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) northeast of Jakarta, it’s geographically in the middle of Indonesia and largely protected from the kinds of natural calamities (earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions) that befall other islands. Construction will begin in 2020 and government offices will start relocating in 2024, along with as many as 1.5 million employees.

3. What’s the economic rationale?

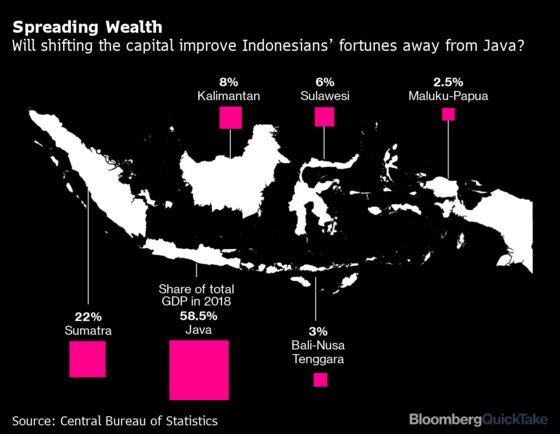

Jokowi, as Widodo is known, says the move will help address income disparity in the archipelago of more than 17,000 islands. Java accounts for almost 60% of Indonesia’s population and contributes about 58% of its gross domestic product. Kalimantan accounts for 5.8% of the population and contributes 8.2% of GDP. The island has reasonably well developed airports and roads and widespread access to drinking water. Authorities have talked about building a modern, smart and green city which can serve as the capital for a century.

4. What’s the cost?

The price tag for building a city from scratch to accommodate 1.5 million people is estimated at 466 trillion rupiah ($34 billion). Projects will be funded by a mix of government, state-owned enterprises, private companies and private-public partnerships. Of those, Jokowi says the smallest burden will fall on the state. Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, SoftBank Group Corp. founder and Chief Executive Officer Masayoshi Son and former British Prime Minister Tony Blair were asked to join an advisory panel, and Indonesia hired McKinsey & Co. to review the master plan. Environmental groups worry about the cost to an already depleted natural habitat. Borneo, home to endangered species such as the orangutan, has lost 30% of its forests in a little over four decades, much of it to the paper and pulp industry and palm oil plantations.

5. Can Indonesia afford this?

Apparently. With Jokowi pitching the new capital as a symbol of Indonesian identity and progress, the project will be part of his legacy, meaning budget is unlikely to be a constraint. The outlay is equivalent to the government’s annual infrastructure spend but will be spread over a decade or so. Indonesia is already splurging, with $350 billion spent of infrastructure projects during Jokowi’s first term and another $412 billion planned for the next five years.

6. Has this worked for other countries?

Indonesian authorities point to successful relocation of at least 30 capitals in the past century, including Brasilia (Brazil), Astana (Kazakhstan) and Canberra (Australia). On the other hand, Naypyidaw, conceived by Myanmar’s junta, remains practically empty. While a new capital will typically host government buildings, it’s rare to see a large-scale uprooting of private business and the general population. Other countries in the process of shifting their capitals include Egypt.

7. What’s the new place like?

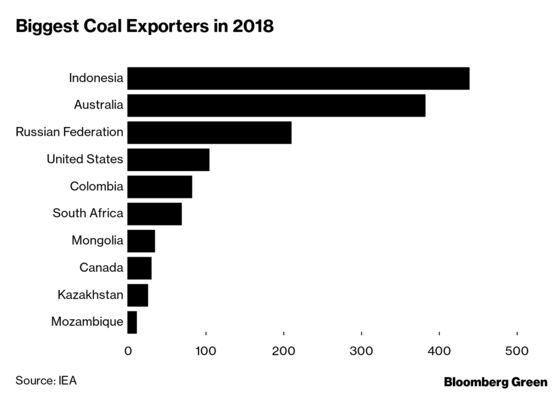

Locals call it coal country, near the the heart of one of Indonesia’s biggest mining regions. The gateway is Balikpapan, a former fishing village that became a boomtown after oil was found in the area in the late 19th century, during Dutch colonial rule. It has grown into a modern urban center and Kalimantan’s financial heart, but an oil refinery run by state-owned PT Pertamina dominates the shoreline. Oil wells still dot the area but the fuel has been overtaken by coal. At PT Bayan Resources Balikpapan Coal Terminal further up the coast, snaking red conveyor belts stretch out into the bay, carrying the fuel to waiting ships. On the other side of the bay, villages still pursue a traditional life based on fishing, but their future is under threat from pollution.

8. What will happen to Jakarta?

It’ll keep growing. The population is on course to reach 35.6 million by 2030, helping it topple Tokyo as the world’s most populous city. The greater metropolitan area, which generates almost a fifth of Indonesia’s GDP, will continue to be the country’s main commercial hub. There’s a $43 billion plan to sort out the traffic, including a Mass Rapid Transit rail line that opened in 2019. As for Jakarta’s submergence problem, the president is planning a giant wall to keep big waves out.

The Reference Shelf

- Bloomberg Green looks at moving a capital to the jungle, in photos and graphics.

- Overtaking Tokyo: Jakarta’s population boom.

- The Economist’s take on the move and Jakarta’s infrastructure needs.

- Andy Mukherjee at Bloomberg Opinion hails the plan.

- The New York Times’ architecture critic reviews Jakarta.

--With assistance from Hannah Dormido and Philip J. Heijmans.

To contact the reporters on this story: Thomas Kutty Abraham in Jakarta at tabraham4@bloomberg.net;Arys Aditya in Jakarta at aaditya5@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Stephanie Phang at sphang@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark, Paul Geitner

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.