What ‘Common Prosperity’ Means and Why Xi Wants It

Chinese President Jinping is on a campaign to remake the world’s second-biggest economy with an emphasis on “common prosperity.”

(Bloomberg) -- Chinese President Xi Jinping is on a campaign to remake the world’s second-biggest economy with an emphasis on “common prosperity.” The hope is that a mix of policy moves, market forces and philanthropy will address the country’s wide and persistent wealth gap, which could become a political threat to the ruling Communist Party if left unchecked. Regulators have targeted some of China’s most successful private enterprises, the data-rich tech sector in particular, alarming investors. They’re also trying to rein in what the government sees as the excesses of civil society, including rabid celebrity fandom, academic cram schools and video gaming.

1. How big a problem is inequality in China?

China’s richest 20% earn more than 10 times the poorest 20%, a wider gap than in the U.S. or European countries such as Germany and France, and one that hasn’t budged since 2015. Though the number of people living in extreme poverty has dropped dramatically over the past decade, more than 600 million people -- about half of China’s population -- live on an annual income of 12,000 yuan ($1,858) or less. At the other end of the spectrum, rapid economic growth and market-based reforms created tremendous wealth: China has 81 billionaires on Bloomberg’s ranking of the world’s 500 richest people, more than any other country after the U.S., and there are thousands more billionaires and multimillionaires who don’t crack the top 500.

2. Is ‘common prosperity’ a new theme?

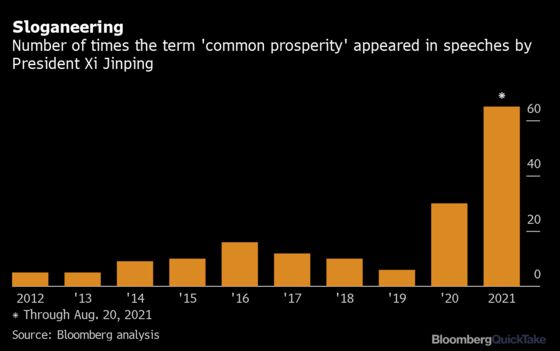

Not at all. The idea was introduced into party documents by Mao Zedong to reflect the pursuit of a more egalitarian society. It fell out of frequent use under Deng Xiaoping, who shifted the focus to developing an economy that would allow “some people to get rich first.” Common prosperity, he said, would come later. Xi made it a central part of his 2017 speech at the party congress to mark the start of his second term, and the messaging really took off in 2021. The slogan has since been adopted by state agencies and private companies as a way to signal their allegiance to this Communist Party priority.

3. Why is this happening now?

It’s hard to know. One theory is it’s part of Xi’s ambition to serve a third term as president, a possibility now that the decades-old system of term limits has been overturned. That’d be easier if he’s popular. Another possibility is that these measures have long been on Xi’s agenda, but other things got in the way. After his 2017 speech, China became embroiled in a broad trade war with the U.S. Then once a deal was reached, the pandemic hit. Now he’s got a clearer path to put the ideas into action. Ahead of its 100th anniversary in July, the Communist Party declared the completion of a long effort to create a “moderately prosperous society.” That opened a door for Xi to set the pursuit of common prosperity as a new guiding principle. (Forecasts from Bloomberg Economics suggest China could become the world’s biggest economy as soon as 2031.) Also, several of China’s tech behemoths are now bigger than the largest state-owned enterprises, and their founders have amassed incredible wealth, which may seem politically threatening to the Communist Party.

4. What has the government done to companies?

China has announced a sweeping overhaul of the $100 billion for-profit education industry, banning tutoring companies from making a profit and teaching the school syllabus on nights and weekends, among other restrictions. It’s announced a reform plan for health-care costs in public hospitals designed to keep prices from rising too quickly, having already tackled excessive charges for drugs and medical supplies. It’s leaned on ride-hailing and food-delivery companies to improve conditions for their low-wage workers. China’s top court issued a long essay detailing how the pervasive culture of excessive overtime -- known as “996” -- may violate the law.

5. And society?

The government seems to be trying to mold model citizens. It extended limits on online gaming for minors, allowing just three hours a week, and used accusations of sexual misconduct at Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. as an opportunity to warn against business drinking. Authorities have vowed to increase investigations of tax evasion among high earners and made a prominent example of actress Zheng Shuang, who was ordered to pay 299 million yuan in overdue taxes, late fees and fines. There’s also a broader effort to weaken stars’ influence among their fans, which is seen as unhealthy and “Western.” Regulators have directed TV and movie studios to cap actors’ salaries and shun those with “incorrect politics” or “distorted aesthetics,” using a derogatory term for effeminate men. Fan sites are no longer allowed to post celebrity rankings and must block access for minors. Zhao Wei, a popular actress with her own business interests, has been mysteriously erased from the Chinese internet for reasons as yet unknown.

6. Is there more coming?

China has been trying for years to make housing more affordable, particularly in the biggest cities, and often blames speculators for driving prices up. There are mounting signs that it’s preparing to move on an idea that’s been discussed for a long time: imposing a residential property tax to deter speculation. The municipal governments in Shanghai and Chongqing have been conducting trials since 2011, levying a tax on second homes or high-priced ones.

7. How far will this go?

The central government hasn’t set any specific goal, leaving everyone to speculate about massive wealth redistribution and the nationalization of private companies. But some investors have also noted Xi’s comments about paying equal attention to enforcing regulation of companies and supporting their development. A pilot program suggests change will be gradual, rather than radical. In June Beijing designated Zhejiang, the wealthy coastal province where Alibaba and Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co. lead a thriving private sector, as a “demonstration zone” to test common prosperity initiatives. The plan calls for more access to education and health care, encourages investment in rural areas and nudges rich people to be more philanthropic. The actual targets, though, are incremental improvements over the status quo, ones Zhejiang was on pace to hit without any policy changes at all. Meanwhile, at least one prominent economist has defended the market economy as the best way to provide opportunity for the masses, arguing that too much government intervention would result in common poverty instead.

8. How are billionaires taking it?

They’re opening their wallets, in line with the government’s call for individual distributions of wealth driven by “moral obligation and social pressure.” Seven billionaires directed a combined $5 billion to charity in the first eight months of 2021, a sum that exceeds all giving nationally the year before. Still more is coming from the private sector. Automaker Geely said it plans to enrich its employees with stock awards. Tencent Holdings Ltd. earmarked about $15 billion for social responsibility programs, and Alibaba pledged $15.5 billion. Pinduoduo Inc. set aside $1.5 billion in future profits for agricultural investments. The flood of donations will accrue primarily to state-backed initiatives.

The Reference Shelf

- QuickTake explainers on China’s billionaires, the “996” work ethic, the property tax idea and the crackdown on tech giants.

- The Jamestown Foundation looked at the Maoist roots of the slogan.

- Bloomberg Opinion’s Tim Culpan describes Xi as the ultimate tiger mom, and Shuli Ren looks at what the crackdown on fan culture means for Alibaba’s Jack Ma, and Anjani Trivedi examines it from the investor perspective.

- The Financial Times thinks China wants to redraw the social contract.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.