Water Crisis Is Compounding an Inflation Time Bomb in Brazil

Brazil’s worst water crisis in nearly a century is fueling inflation that’s reverberating through the economy.

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil’s worst water crisis in nearly a century is fueling inflation that’s reverberating through the economy, posing an additional challenge for the central bank and for President Jair Bolsonaro’s re-election bid.

Electricity bills will increase as much as 15% next month as dangerously low water levels in hydroelectric reservoirs force the government to turn to more expensive power plants fueled by natural gas, diesel or coal, according to calculations from Fundacao Getulio Vargas, a Brazilian think tank. Food prices are also going up as farmers lose part of their crops to the drought.

Combined, those issues would already spell trouble in a country where annual inflation is running at over 8%, the fastest in five years and more than double the target. XP Investimentos SA estimates they will account for 1 percentage point of this year’s price rises. But the situation in Brazil is more complicated because the government has been postponing part of the annual increases to which power distributors are entitled in a bid to ease the economic impact of the pandemic.

The upshot is that Bolsonaro has no good choices, with some bound to hurt his popularity going into next year’s presidential elections and most options damaging the economy to a greater or lesser extent.

“The government has set up a time bomb for 2022,” said Adriano Pires, director at the Brazilian Center for Infrastructure, an energy consultancy firm. “We need to see how they’re going to handle this; governments tend to hold prices until elections and then see what to do.”

Economists still don’t have precise estimates for how much electricity prices will increase next year as that will depend not only on the weather -- critical in a country that relies on hydropower plants to generate as much as 70% of its electricity -- but also on how the government will manage growing cost pressures building up from the increased deployment of thermoelectrics.

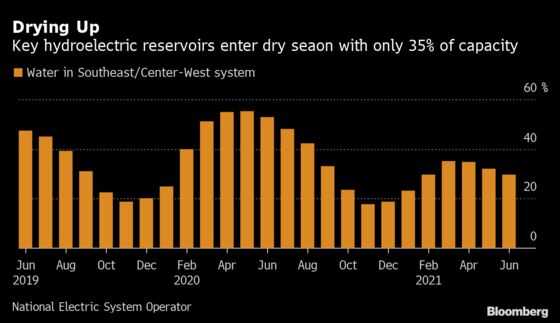

Rainfall in Brazil this year has been the scarcest since data started being recorded in 1931. Water reservoirs in the country’s southeast and center-west regions, where its largest hydropower plants are located, have entered the dry season in March with only 35% of their capacity. When rains hopefully resume in November, they may be running at little more than 7%, according to government estimates.

Political Challenge

Bolsonaro’s government wants to avoid at all costs a power rationing similar to that implemented by Fernando Henrique Cardoso two decades ago -- one of the factors contributing to the decline of his popularity and the subsequent election of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in 2002.

Click here to read more about Brazil’s 2001 power rationing

The discussion is so thorny that Lower House Speaker Arthur Lira, a government ally, flip-flopped on the topic. After saying on June 22 that Brazil would need to implement some sort of power rationing this year to avoid blackouts, he amended himself just hours later, explaining that there will actually be “incentives for the efficient use of energy by consumers, on a voluntary basis.”

That idea was reinforced by Deputy Energy Minister Marisete Dadald. “We are not talking about rationing, we are working hard to ensure electricity supply to those who need it,” she said in an interview.

One of the alternatives considered is to sign agreements with industry to reallocate production during times of the day where there’s less demand for electricity, Dadald said.

Inflation Problem

For now, Brazil doesn’t need to impose a power rationing. Unlike in 2001, the country has enough thermo generation capacity to make up for hydroelectric losses. The problem is its price: on average, thermoelectricity is over three times more expensive than energy generated by hydropower plants.

Pires estimates that thermopower plants may remain in use until at least April 2022, when the government will reassess whether enough rain has brought water reservoirs back to safe levels before next year’s dry season.

That means a so-called red flag surcharge to electricity bills will likely remain in effect until then. Right now, a red flag raises the price of energy paid by consumers by about 10%, according to Andre Braz, an economist and inflation specialist at Getulio Vargas Foundation. But power regulator Aneel is preparing to increase the red flag surcharge, which could mean an additional 15% increase to electricity bills, Braz said.

Aneel said its base-case scenario contemplates the deployment of thermopower plants until October, without ruling out a later date. Its director general, Andre Pepitone, said all will depend on the amount of rains, which have been below average during the past seven years. He considered talk of a time bomb for 2022 “alarmist,” saying there are tools to be used to smooth out the increase in generation costs.

“Our scenario is that 2022 will bring no additional surprises,” he said in an interview.

Brazil’s inflation is forecast to end at 5.9% in 2021 and 3.78% in 2022, above the targets of 3.75% and 3.5% for each year, respectively, according to economists surveyed by the central bank. Struggling to bring down such expectations, policy makers left the door open for a bigger increase to the benchmark interest rate in August, following three consecutive hikes of 75 basis points.

Yet the degree of uncertainty for next year’s inflation remains high amid concerns that rainfall may remain below historic averages once again.

“Electricity prices in 2022 depend on rains and the pessimism is growing,” said Braz. “A power rationing now would be an intelligent way of dealing with the crisis to avoid blackouts if the situation worsens.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.