Wall Street Sees Treasury With Debt Limit Break-Glass Plan

Wall Street Still Sees Treasury With Debt Limit Break-Glass Plan

(Bloomberg) -- The Treasury Department says it has no plan to sort through which payments it would make, and which U.S. government obligations it would set aside, once it exhausts measures to avoid breaching the federal debt limit. Wall Street sees it differently.

In a worst-case scenario, the options of prioritizing payments on publicly held U.S. Treasuries, or delaying some debt-payment dates, are still technically on the table, some strategists are telling their clients.

Treasuries -- the world’s biggest bond market -- and their liquidity are the foundation of the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency, adding to the argument that they would be put ahead of other obligations.

Confidence that those payments would be prioritized stems in part from a once-secret debt-limit contingency plan from the Obama administration that Secretary Janet Yellen’s team is at this point saying it won’t tap. Details were discussed by Federal Reserve officials during highly contentious battles over raising the debt ceiling in 2011 and 2013, as shown in transcripts of Fed conference calls.

“What the transcripts tell me is that the Treasury is able to prioritize payments,” said Mark Cabana, head of U.S. interest-rates strategy at Bank of America Corp. Their willingness to do so “is a separate question,” he said. “Even if you just acknowledged the possibility, it would be very politically unpopular to say you are going to essentially pay China and Japan over paying Social Security recipients.”

‘On Time’

Japan and China are the two largest foreign holders of Treasuries, with over $1 trillion each.

The Treasury isn’t engaging in discussion of what would happen if Congress fails to suspend or increase the debt limit, which kicked in at $28.4 trillion at the beginning of August following a two-year suspension. Yellen said earlier this week that extraordinary measures to avoid breaching the limit will only last until sometime in October.

The U.S. “pays all its bills on time,” Treasury spokeswoman Lily Adams said Wednesday. “The only way for the government to address the debt ceiling is for Congress to raise or suspend the limit, just as they’ve done dozens of times before.”

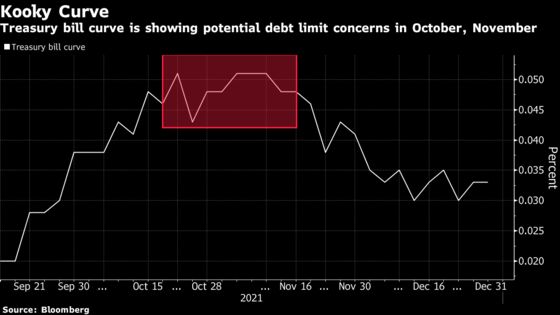

The Treasury market is showing some signs of concern about Congress failing to act in time. Yields on bills that come due in late October or early November are higher than those that mature before or after, as investors ask for more compensation for the added risk.

By contrast, it’s possible that yields on longer-dated Treasuries drop amid haven demand, JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategists said.

“Yields on bills may move higher and coupon yields may move lower the longer the debt limit remains unresolved,” JPMorgan strategists led by Alex Roever wrote in a note Friday.

Wrightson ICAP expects the so-called drop-dead date -- when the government’s cash and extraordinary measures run out -- to be around Oct. 22. Bank of America’s Cabana says it could happen by early November -- but he’s assuming Congress lifts it or suspends it again before that.

Read more: Traders Alert to T-Bill Risks as U.S. Approaches Debt-Cap Breach

Politics has again complicated addressing the issue. Democratic congressional leaders and the Biden administration have called on Republicans to join in backing a suspension or increase, but most GOP senators have said they’ll oppose the move.

The standoff raises the risks to the outlook for the U.S.’s credit rating, according to Thomas Torgerson, co-head of sovereign ratings at DBRS Morningstar.

“Absent a shift in strategy from at least one of the two parties, the risk of miscalculation grows with every passing day,” Torgerson said in a recent report.

Rating Risk

Even if payments were sustained on Treasuries, defaulting on some of the myriad of other government obligations -- from Social Security to paying for regular federal government operations -- could badly damage perceptions of U.S. sovereign credit quality.

S&P Global Ratings in 2011 downgraded the U.S. after a protracted -- but ultimately successful -- battle to lift the debt limit. Amid another such struggle two years later, Fitch Ratings put the U.S. on negative watch. Fitch went on to remove the designation in 2014, before putting it back on in July 2020.

During a 2017 round of problems over the debt limit, Moody’s Investors Service said it expected the Treasury to turn to prioritizing debt servicing over other obligations if needed.

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, says that if that did come to pass, it would raise U.S. borrowing costs nevertheless given the damage of failing to make good on other obligations, even if just for a limited period.

“There’s a not-inconsequential risk in this go-around that there’s a mistake here -- and a default,” Zandi said in a phone interview Thursday. “I’m sure Treasury is looking at all kinds of break-glass scenarios” such as prioritization, he said. “But this is break-glass stuff, which means we’d be in a crisis and it would be cataclysmic and we’d be going off the rails.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.