Venezuela Bond Loophole Could Affect Creditor Claims

Venezuela’s Default Loophole Means Creditors Could Lose Billions

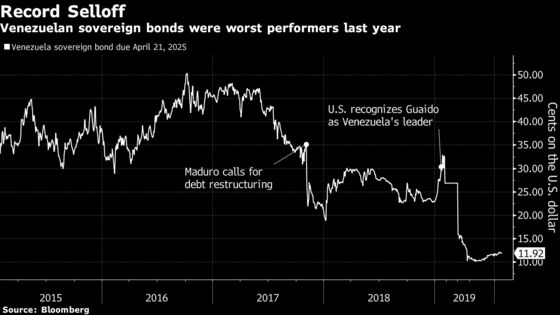

(Bloomberg) -- As Venezuela enters its third full year in default, its obligations have become something of an afterthought to even its biggest creditors.

Worth just pennies on the dollar, tens of billions in bonds routinely go days at a time without trading. Sanctions bar U.S. investors from buying them and make the prospect of a full-scale restructuring all but impossible. And with no end in sight to the political stalemate in Caracas, it’s no wonder few creditors have taken the costly step of taking the government to court.

Yet that might soon turn out to be an even costlier mistake.

Buried deep inside the prospectus of every sovereign bond issued since 2005, or nearly $30 billion worth, is a little-known clause that, based on some legal experts, could let Venezuela off the hook on unpaid interest to any creditor after three years -- provided the creditor doesn’t take legal action seeking repayment during that span. Known as a “prescription clause,” it cuts the standard statute of limitations in half for bonds governed by New York law, they said. So with the third anniversary of the country’s default coming in November, creditors caught unawares could wind up forfeiting billions of overdue interest payments.

None of the bondholders contacted by Bloomberg News said they were aware of the clause. Nor was Mitu Gulati, a law professor who specializes in sovereign bond contracts at Duke University. So rare is the clause that Gulati says he has only ever seen it in a handful of bond documents.

“This is definitely an advantage for the debtor because as a creditor you can lose all your rights if the clock runs out,” said Gulati, who reviewed the documents, which often run hundreds of pages long.

Mark Walker, who advises one group of creditors as head of sovereign advisory at Guggenheim Securities, disagrees and said there’s no urgency for bondholders to act. He argues that the relevant date isn’t the default date. Instead, he says the three-year statute of limitations on interest payments provided by the clause only starts after Venezuela has deposited funds to financial intermediaries responsible for transferring payment to bondholders -- which he says hasn’t happened.

“Venezuela is in default of virtually all bond payments and no Fiscal Agent has received any such payment on any of the relevant Venezuelan bonds,” according to a statement from the Venezuelan Creditors Committee. “Thus, the contractual three-year limitations period has not begun to run.”

Some legal experts say the clock was triggered by the default itself because the government said it had previously sent bond payments to financial intermediaries that were held up by U.S. sanctions.

Whatever the case, the clause isn’t intended to be an all-purpose, get-out-of-jail-free card for the issuer. Absent a debt renegotiation, Venezuela is still legally obligated to repay the principal it owes in full. And for creditors who face the prospect of steep losses on their capital in any grand bargain with Venezuela, overdue interest might not be at the top of their list of concerns.

Nevertheless, at stake is the risk of relinquishing the right to recoup billions of dollars, if the clause is interpreted to mean the statute of limitations is shortened. Precise numbers are hard to come by, but Venezuela will owe at least $2 billion in accrued interest by the time the statute of limitations expires. The clause could also impact future cash flows as they come due, causing the amount to balloon over time.

An official at Venezuela’s finance ministry declined to comment. According to a person close to the ministry, the Maduro government is studying the issue to find a solution before the upcoming deadline.

A representative for his rival, Juan Guaido, the opposition leader recognized by the U.S. as the rightful head of state, also declined to comment beyond a July statement laying out his team’s debt-restructuring principles. In it, Guaido’s team asks creditors to refrain from pursuing legal remedies and said it would “entertain” proposals to extend any statute of limitations as it seeks to renegotiate its debt.

Venezuela Congress Approves $20m Fund for Litigation Abroad

Origin Story

Most of the securities containing the clause were originally sold in the domestic market as part of a government effort to alleviate pressure on its tightly-controlled currency market. Local investors were allowed to buy the bonds with bolivars and then flip them in international markets as a means to obtain much-needed dollars. Currently, the biggest bondholders include Pimco, BlackRock Inc. and Grantham Mayo Van Otterloo & Co. They declined to comment on the clause.

It’s unclear who actually suggested inserting the clause, which has appeared in documents governing the bonds issued by both the governments of Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro for over a decade. One senior banker involved in the offerings was surprised it existed and couldn’t recall how it got there. Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer and Sullivan & Cromwell, which drafted the prospectuses as legal advisers at the time, also declined to comment.

Of course, investors can prevent their claims from becoming void by making a “presentation for payment” within the required period. Whether this means sending a letter requesting payment, filing a lawsuit or gathering a group of creditors to demand immediate repayment of a particular bond is open for interpretation, according to legal experts.

Venezuela’s intentions are also up for debate. The Maduro government, which the Trump administration has tried to isolate by supporting Guaido, could use the clause as a bargaining chip to win over creditors as it seeks fresh financing and political support abroad. One possibility is offering to extend the statute of limitations as a sign of good faith, people familiar with the matter said.

“The Maduro government can use this to motivate U.S. investors to reach a deal,” said Temir Porras, a former senior aide to Chavez and Maduro. “This gives the government more leverage.”

If the lawsuits do start to pile up, it wouldn’t be Maduro’s problem anyway.

Because U.S. courts recognize Guaido (and not Maduro), it’s his team that would be on the hook for the legal fees and all the various headaches that come with litigation. What’s more, Guaido’s top legal advisers have been under pressure this week after the opposition-led National Assembly approved a $20 million litigation fund, drawing criticism from some lawmakers about a lack of oversight. Guaido, for his part, has long indicated he intends to play hardball when it comes to bondholder claims because the country needs to earmark as much money as possible to help everyday Venezuelans.

--With assistance from Nicolle Yapur.

To contact the reporter on this story: Ben Bartenstein in New York at bbartenstei3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, ;Carolina Wilson at cwilson166@bloomberg.net, Michael Tsang, Larry Reibstein

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.