War Exposes Europe’s Failure to Heed Warnings Over Russian Gas

War Exposes Europe’s Failure to Heed Warnings Over Russian Gas

(Bloomberg) -- On a freezing winter morning, Europe woke up to a shock. Russia had cut off gas to Ukraine. Companies started reporting drops in supplies via the transit country. Calls to reduce energy dependence on Moscow resonated across the continent.

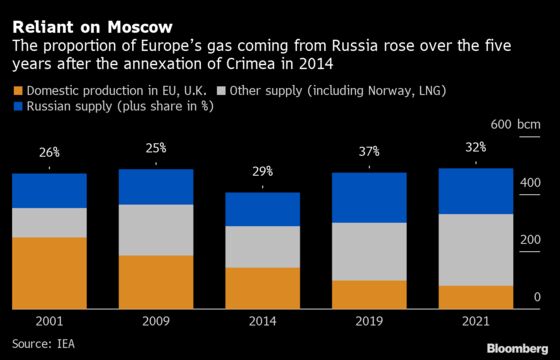

That was in January 2006. Sixteen years on, through another supply crisis and then Russia’s annexation of Crimea, the European Union is much in the same place: plotting ways to cut reliance on its single biggest gas supplier and bracing for a stoppage of flows as Russia wages war on Ukraine.

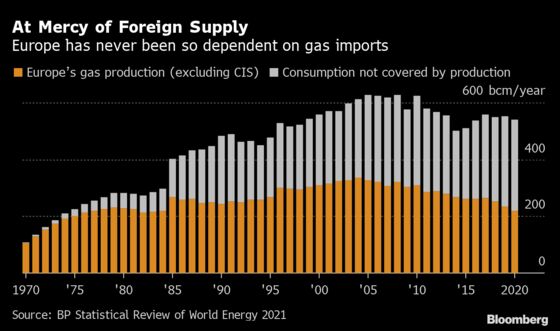

The awkward reality for Western Europe is that however much the writing was put on the wall, energy policy came from a different script. Europe’s ambition is to lead the global fight against climate change by shifting away from fossil fuels, but it’s so far failed to translate into a weaker role for gas in the economy. And that also means Russia.

Dwindling domestic gas production means that the EU is more dependent on foreign suppliers than ever. Russia’s export company Gazprom PJSC provides at least 40% of imports into the bloc. The figure was more than 60% for Germany, Europe’s largest economy, in 2020.

At the same time, the growing political leverage that Russia built with Nord Stream, an undersea pipeline linking Russia with Germany and bypassing Ukraine, rang alarm bells in former communist members of the EU. Then Berlin’s policy of economic rapprochement with the Kremlin paved the way for an expansion of the gas project — Nord Stream 2 — which was halted by Germany only after the invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces on Feb. 24.

“Despite the warning signs, appeasement of Russia has failed to prevent a war in Europe,” said Manfred Weber, German chairman of the European People’s Party, the biggest political group in the European Parliament. “Europe was too naive, too much focused on economic cooperation.”

EU Energy Commissioner Kadri Simson said in an interview on March 3 that the situation right now isn’t comparable with the disruption 16 years ago because the EU is better prepared and has closer cooperation. She acknowledged that Russian companies “still have extraordinary market share in our natural gas market.”

From Simson’s predecessor at the time to Austria’s economy minister, though, the political messages back in January 2006 were clear: Europe must diversify its energy sources. And the scale of the challenge was already visible several months later.

That October, Russian President Vladimir Putin arrived in Dresden for his fifth meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel of the year. He laid out his vision for Germany: Nord Stream would transform the country from just a consumer into Europe’s largest gas hub.

Countries like Poland, which joined the EU in 2004 along with other former Eastern Bloc nations, were already warning over Russia using gas as a political weapon.

Radoslaw Sikorski, then Poland’s defense minister, compared Nord Stream — which circumvented Polish territory — with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that carved up Poland between Germany and the Soviet Union before World War II. The leaders of France, Germany and Italy downplayed the concerns.

Then, before the controversial pipeline under the Baltic Sea started operations, supplies of Russian gas to Ukraine were halted again at the start of 2009 amid another pricing dispute between the two neighbors now at war.

Exports to several EU member states were first drastically cut in freezing temperatures and then stopped, further undermining the reputation of Ukraine as a transit country for about 80% of the Russian gas at that time.

The joint venture between German companies BASF AG and EON SE with Gazprom saw the first gas pumped into their new pipeline in 2011. The same year studies began on the option to add Nord Stream 2. Germany’s decision to phase out nuclear power after the Fukushima disaster was set to strengthen the role of Russia as the strategic supplier.

The reaction in Eastern Europe was an even greater resolve to diversify supplies. Poland, which relied on Gazprom for some 70% of its gas imports, started the construction of a liquefied natural gas terminal, eyeing deliveries from countries such as Qatar and the U.S.

Polish imports from Russia are now at around 60% and the share of LNG is close to 25%. Poland’s long-term gas contract with Russia expires at the end of this year and the government in Warsaw doesn’t plan to extend it.

“This underscored the difference in perception between Western and Eastern Europe on the role and intentions of Russia as a main gas supplier,” said Jerzy Buzek, a member of the European Parliament and a former Polish prime minister. “The invasion of Ukraine was then an eye-opening moment for many in the West, while the East has already gained more independence before, also thanks to EU financial and regulatory support.”

The Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 further deepened the energy fault line along Oder-Neisse, the post-World War II boundary first proposed by the Soviet Union at the Yalta Conference in 1945 and which still forms the present-day border between Poland and Germany.

The European Commission was designing plans to diversify supplies, but the challenge was that energy policy remains largely in the hands of member states. They have the sovereign right to decide about their choice of energy sources and pursue varying interests.

To wean off Russian gas, the EU was betting on a build-up of renewables and greater energy savings. While the share of sources such as solar and wind started to increase, their intermittent nature amid limited storage options meant backup was needed.

“Hindsight is a great thing, but we should have all taken climate, renewable energy policies and energy efficiency much, much more seriously than we did,” said Peter Vis, senior adviser at Rud Pedersen Public Affairs in Brussels and a former top official at the EU Commission.

What the EU executive managed to agree was stricter oversight of gas contracts with Russia and rules that boosted the security of gas supply in the region in the case of a crisis. The introduction of reverse flows means Russian gas may now flow from the west to the east of the bloc and beyond its borders, to Ukraine.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, meanwhile, couldn’t come at a more sensitive moment in the EU energy debate. The bloc is looking at how to implement its goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2050 as energy prices soar and the closure of German nuclear plants adds to concerns about energy security.

German Economy Minister Robert Habeck said reducing dependency on Russia won’t happen overnight, though the war in Ukraine has heightened the resolve. “We’ve gotten ourselves into quite a corner there,” he told Deutschlandfunk radio on March 2. “But now we want to get out of it.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.