U.S. on Sidelines as Allies Struggle for New Venezuela Strategy

U.S. on Sidelines as Allies Struggle for New Venezuela Strategy

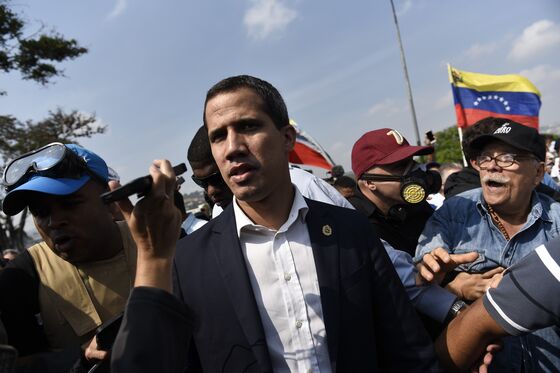

(Bloomberg) -- When Donald Trump recognized Juan Guaido as the rightful leader of Venezuela in January, 50 governments quickly lined up behind the American president in an impressive show of Western unity.

But as the effort to dislodge Nicolas Maduro stalls out, many of those countries are charting new diplomatic paths on Venezuela, ignoring American calls not to negotiate with him. Recently concluded talks in Norway and separate discussions between Europe and both sides of the Venezuelan divide have effectively pushed the U.S. to the margins.

While there’s widespread concern that Maduro isn’t negotiating seriously, a senior European diplomat said a new approach is needed because U.S.-led efforts to overthrow the regime have failed. Interviews with about a dozen European and Latin American officials made clear that they are acting not only out of desperation for Venezuela’s future but doubts that the U.S. approach can work.

William Burns, a former U.S. deputy secretary of state, said Washington built an effective global coalition against Maduro but then picked needless disputes with its partners. “Passive-aggressive threats of U.S. military action” wound up helping Maduro consolidate his grip on power, he said.

“The administration quickly fell into a number of traps which have bedeviled its foreign policy elsewhere,” said Burns, who is president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “It picked maximalist objectives that far outstripped its capacity and willingness to invest in the necessary means.”

And while such concerns are widespread, the likelihood of success in these talks also appears slim. Previous efforts to negotiate with Maduro have shown that his overriding aim is to stay in power, whereas the goal of the opposition and the dozens of countries backing Guaido is to remove him from power.

That is the argument made by the Americans who dismiss any possibility of success from these negotiations. State Department spokeswoman Morgan Ortagus said May 25 that “The only thing to negotiate with Nicolas Maduro is the conditions of his departure.” Speaking on condition of anonymity, a top U.S. official added that the Maduro regime knows that sanctions are biting and hopes to use talks to alleviate them, not establish free elections.

Moreover, the official said, if Maduro holds power during any political campaign, with the ability to intimidate and detain opponents, it won’t be a free election and no one will accept its results. A European diplomat admitted frustration after recent sit downs with Maduro, who has so far not indicated any willingness to allow a presidential vote to take place. The official said that for the Maduro government’s calls for dialogue to be taken seriously, a commitment to an electoral timeline needs on the table.

Even among European nations, there isn’t a unified approach to how to go forward. Some governments favor the recently concluded talks in Oslo, which didn’t generate a breakthrough but are expected to restart, while other U.S. allies prefer working through the so-called Lima Group of nations, led by Latin American countries.

In an attempt to forge a more unified approach, foreign ministers from the International Contact Group and the Lima Group met in New York on Monday to advocate for a “peaceful transition leading to free and fair elections.”

“We are going to put all our efforts to support the Venezuelan people in order to restore democracy as soon as possible,” Nestor Popolizio, Peru’s minister of foreign affairs, told reporters at the UN.

But specifics on how to do that were still missing.

Luis Almagro, the head of the Organization of American States, said the variety of uncoordinated approaches shows a lack of strategy and cohesion on the part of the international community that only serves to buy Maduro time. Almagro backs a strategy that involves economic pressure and a credible threat of force.

‘Weakest Point Ever’

“Maduro is at his weakest point ever, this is the moment to push forward and not back down,” said Almagro. “This is not a conflict between two parties that you can solve with dialogue. There’s been dialogue with the regime on and off since 2003. This is a dictatorship ruling over a people who are seeking their human rights.”

Even within the Venezuelan opposition, which has a long history of fracturing, there isn’t unanimity on the talks. Carlos Blanco, who works closely with Maria Corina Machado, an opposition leader, called the Maduro government “a criminal corporation” and said expecting it to step down “is not credible.”

North Korea Example

Nonetheless, global consensus has defaulted toward these halting diplomatic efforts. One Latin American diplomat argued that if Trump can talk to North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, there’s no reason there shouldn’t be an effort at negotiations with Maduro.

The European-led International Contact Group, formed to facilitate new presidential elections in Venezuela, has met with both sides and is coordinating with the Lima Group. In a sign of increasing seriousness, the European Union appointed Enrique Iglesias, a former Uruguayan foreign minister, as a special envoy to the crisis.

In Oslo, representatives from Maduro’s regime and the opposition met face to face, according to diplomats and lawmakers. Government representatives focused on the release of political prisoners and the easing of international sanctions. Opposition officials demanded more concrete proposals as a prerequisite for further talks, they said.

Lost Immunity

Expectations of success remain low as the government cracks down on foes and the opposition’s street movement loses steam. Last Wednesday, the Supreme Court, stacked with Maduro loyalists, stripped the parliamentary immunity from another opposition lawmaker, meaning there are now over a dozen anti-government politicians being probed for treason in connection with a botched military uprising spearheaded by Guaido in April.

“I understand the criticism that can arise,’’ Guaido said recently. “We don’t believe in the good faith of those who brought us to this catastrophe.”

The U.S. is also struggling. While American officials repeatedly say all options are on the table, the Trump administration hasn’t been willing to deploy military force. Its effort to revoke Maduro government credentials at the United Nations has also hit a wall. In April, Vice President Mike Pence announced the U.S. would soon produce a resolution aimed at giving Guaido’s envoys a seat at the UN, but several diplomats say the U.S. hasn’t introduced the resolution because it can’t get the necessary majority at the General Assembly.

Meanwhile, humanitarian conditions in Venezuela have continued to worsen. An April report by researchers at Human Rights Watch and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health said Venezuela’s health system is in “utter collapse,” citing the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles and diphtheria and rising infant mortality. Talks may be a long shot, but they’re the only possible way out of this morass, said Jose Singer, Special Envoy of the Dominican Republic to the UN.

“There has to be dialogue, even if it seems difficult,” Singer said in an interview. “We eventually have to create a credible path to restore democracy.”

--With assistance from Gregory Viscusi, Samy Adghirni, Ilya Arkhipov, John Follain and Robert Hutton.

To contact the reporters on this story: David Wainer in New York at dwainer3@bloomberg.net;Ethan Bronner in New York at ebronner@bloomberg.net;Andrew Rosati in Caracas at arosati3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Bill Faries at wfaries@bloomberg.net, ;Juan Pablo Spinetto at jspinetto@bloomberg.net, Robert Jameson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.