U.S. Economy Too Fragile for Congress to Remove Income Support

After approving the most generous unemployment benefits in U.S. history, Congress is in a bind over what to do when they expire.

(Bloomberg) --

After approving the most generous unemployment benefits in U.S. history to help counter the coronavirus, Congress is in a bind over what to do when they expire at the end of next month.

With America gradually heading back to work, there’s no majority among lawmakers to extend the $600-a-week extra payments in their current form. But with the economy more fragile than it’s been in generations, they don’t dare to just pull the plug.

That means weeks of wrangling lie ahead over how to extend a rescue effort already costing almost $3 trillion. Republicans aim to keep the bill for the next phase of stimulus, which may include more cash for state or local governments and liability protection for business as well as jobless benefits, below $1 trillion.

Almost 2 million more Americans filed for unemployment last week, according to data published Thursday. While that’s slightly below the figures in the previous couple of weeks, it’s further evidence that U.S. labor markets remain mired in the deepest slump since the Great Depression.

The Senate announced late Wednesday that it will hold a hearing next week on unemployment benefits. Any plan that emerges will have to meet the concern, mostly voiced by Republicans, that too-high payments have become a disincentive to work. And it will have to win votes from Democrats who control the House and are pushing to keep safety nets in place for the tens of millions of Americans who’ve lost their jobs during the pandemic.

There are some indications of what a compromise could look like. One plan winning support from the Trump administration would redirect stimulus into topping up wages for the re-employed -- a so-called “back-to-work bonus.” A separate Democratic proposal would gradually whittle the jobless benefits back to pre-crisis levels as unemployment rates fall.

‘Off a Cliff’

Both ideas have at least the potential to win across-the-aisle support. They could even be combined with each other.

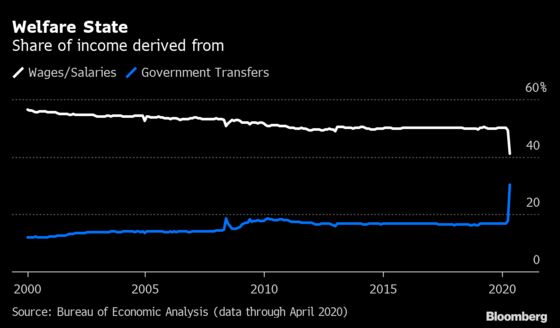

Doing nothing, and simply allowing the additional unemployment payments to expire without a substitute, is an option that has little support -- and would risk torpedoing the economy, after a crisis that’s left households relying on government benefits for a record chunk of their income.

“At the end of July, in that stage of the economic recovery, we really don’t want to see consumer spending go off of a cliff,” said Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities who worked with Democatic presidential candidate Joe Biden when he was vice president. “Any kind of snapback to basic unemployment benefits would be a disaster.”

The federal top-up of $600 a week was approved with bipartisan support in late March as part of the first big package of pandemic measures, though many Republicans at the time thought the figure was too high and the duration too long. Delivery has been hobbled by overloaded local systems and unexplained shortfalls.

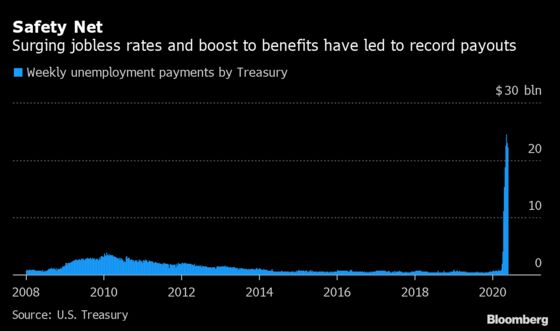

Even so, the Treasury has coughed up about $150 billion of unemployment payments under the plan -- equal to about 4% of GDP in the period, and more than it spent in the whole of 2009, when jobless rates peaked after the financial crisis.

U.S. economic output will likely be higher this year if the benefits are extended through January 2021 than if they’re allowed to expire, as the extra payments prop up demand by allowing laid-off workers to spend “closer to what they spent when employed,” the Congressional Budget Office said in an analysis published Thursday.

But it predicted that the opposite will likely be true next year, when the extended benefits may result in lower output by deterring people from returning to work. “The effect of the reduced labor supply would, in CBO’s assessment, last longer than the effect of increased overall demand,” it said.

White House Warm

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell insists the $600 federal contribution, which is paid on top of each state’s normal jobless benefit, won’t be renewed after next month.

White House officials are showing interest instead in the so-called “back-to-work bonus” proposed by Ohio Senator Rob Portman.

The plan would offer a $450 weekly benefit to each returning worker in addition to their salary -– mirroring the top-up for jobless benefits. Kevin Hassett and Larry Kudlow, two of President Donald Trump’s top economic aides, have both signaled support for the idea in recent days.

Advocates say the plan will be especially helpful for small businesses that have had trouble getting employees to return, while critics say it would expose lower-income Americans to bigger risks from the pandemic.

“I worry that a back-to-work bonus is a bribe to take a lousy, unsafe job,” said Bernstein. Still, he acknowledged that the proposal would address the incentive question.

‘Self-Fulfilling’

Congress landed on the $600 figure because together with state benefits, it added up to the average weekly wage -- so anyone earning that amount would see their full income replaced if they got laid off.

But in fact, job losses have been concentrated among Americans on below-average wages. As a result, about two-thirds of those eligible for the beefed-up unemployment payments will be collecting more in benefits than they earned while working, according to a study by University of Chicago economists. The CBO estimates that ratio could rise to five out of six recipients if the benefits are extended.

Ron Wyden, the top Democrat on the Senate Finance Committee, is calling for a gradual reduction of the payouts. Under his plan, the federal top-up would stay at $600 until unemployment in a given state drops below 11% -- and then decline by $100 for each percentage point that the jobless rate falls, until it’s phased out completely.

Kyle Pomerleau, resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, says that idea has the merit of avoiding arbitrary cutoffs while unemployment is still elevated. Still, he worries that “if the benefit is high enough, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy -- if people are staying home, and then you never actually hit the threshold to start winding it down.”

‘Not a Myth’

Neither Portman nor Wyden have released estimates of the cost of their plans, which would be tough to arrive at anyway amid so many unknowns. But even if their precise numbers don’t survive weeks of bargaining, the ideas behind the two proposals –- tapering jobless benefits, and shifting some of them to the newly re-employed -- may feed into whatever compromise emerges.

Senator John Thune, the No. 2 Republican in the chamber, said talks on the next package will take into account an extension of some unemployment benefits, as well as incentives for employees who go back to work, when they get under way this month.

Lawmakers shouldn’t be making policy in the expectation of a quick rebound in job markets, according to Wayne Vroman, a labor economist at the Urban Institute.

“It’ll be a long time until the U.S. gets back to single-digit unemployment,” he said. And meanwhile, “unemployment insurance is the only income for people who have been laid off. The anti-poverty effectiveness of it is not a myth.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.