U.S. Default Date Is the Estimate That Congress Wants and Yellen Can’t Give

U.S. Default Date Is Estimate Congress Wants, Yellen Can’t Give

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

As the federal debt limit brings a disastrous government default ever closer, Congress will turn to the Treasury Department for the one thing it cannot deliver: a precise deadline.

House lawmakers this week are scheduled to vote on an increase in the debt ceiling, with no likelihood of passage in the 50-50 Senate assuming Republicans vote en masse against it. That leaves the Treasury on track to run out of cash, as Secretary Janet Yellen has said, “sometime in October.”

Given the massive economic and financial disruption that a U.S. payments default would cause, a drop-dead date for the Treasury running out of cash would offer lawmakers -- whether Democrats on their own or in concert with the GOP -- the ultimate prod to action.

“It has to get to Code Orange,” said Representative Jimmy Gomez, a California Democrat.

But there won’t be any advance ‘Code Orange’ from the Treasury. Former officials explain that, because of the volatility in U.S. government cash flows, it would be nearly impossible, and politically risky, for Yellen to give lawmakers a date for when the Treasury will run out of its so-called extraordinary measures to avoid breaching the limit.

“Honest to god, you just don’t know,” said James Clark, who was the Treasury’s deputy assistant secretary for federal finance during a 2013 episode when Congress took the debt-limit debate to the brink. “Tens of billions of dollars can swing unexpectedly. Everyone knows there’s uncertainty. The whole thing is ridiculous.”

Long-time bond market analyst Lou Crandall at Wrightson ICAP’s latest estimate is for the Treasury to exhaust its fiscal resources on Oct. 25 or 26. “The range of uncertainty around our modal estimate narrows a little with each new data point but -- with a month still to go -- remains quite wide in absolute terms,” Crandall wrote in a note Monday.

Effectively, lawmakers are headed for a cliff they cannot see clearly -- and the cliff is moving. Should the government run over it, the U.S. would default on its financial obligations. Social Security checks would stop, federal contractors would go unpaid and -- in a potentially disastrous move for global financial markets -- investors in Treasury securities wouldn’t receive interest payments or get back their principal on maturing bills, notes and bonds.

The resulting chaos, Yellen warned this month, would cause “irreparable damage to the U.S. economy and global financial markets.”

Democrats could have raised the debt ceiling already by using a method that required a simple majority in both houses, bypassing the filibuster -- which otherwise needs 10 Republican votes in the Senate. But House Speaker Nancy Pelosi highlighted in a letter to Democratic colleagues Sunday that “Since 2011, every time the debt limit has needed to be raised, Congress has addressed it on a bipartisan basis, including three times during the last administration.”

“When we take up the debt limit this month, we expect it to be bipartisan once more,” Pelosi said.

But 46 GOP senators have pledged not to vote for a debt-limit hike, tying their hard-line position to opposition to a $3.5 trillion tax and social spending package that Democrats are working to push through Congress on their own.

Against that backdrop, members of Congress are pressing the Treasury for the so-called x-date, when the money is likely to run out.

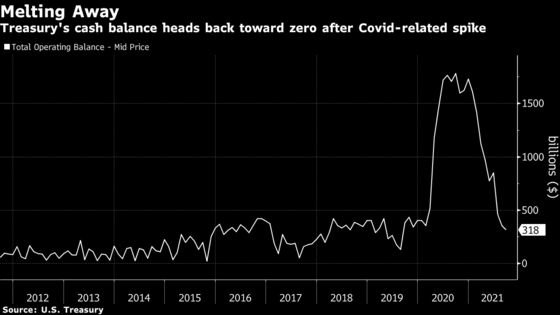

The limit kicked in at $28.4 trillion at the beginning of August following a two-year suspension. Since then, the Treasury has been drawing on its cash pile and withholding contributions to certain programs -- the “extraordinary measures.”

It’s unrealistic to identify the specific date for when those efforts will run out, former Treasury insiders say.

A team of civil servants in the Bureau of the Fiscal Service is charged with forecasting, in as much detail as possible, day-to-day revenues and expenditures. Yet those can be thrown off by changing economic conditions that affect tax collection and by unexpected spending demands. Yellen has argued that the pandemic has made predictions especially difficult, on both sides of the ledger.

“Each day that gets closer, it just becomes exceptionally stressful,” Clark said. “You’re waiting for a shoe to drop, a forecast to be missed.”

The uncertainty also creates political risk.

If Yellen were to give Congress a precise date but cash dried up ahead of that, she may get blamed for a default. Conversely, if Congress doesn’t lift the ceiling and the Treasury is able to hang on for a few days past the deadline, she might be accused of having misled Congress in order to apply pressure.

In an opinion piece Sunday in the Wall Street Journal, Yellen reiterated that, “Sometime in October -- it is impossible to predict precisely when -- the Treasury Department’s cash balance will fall to an insufficient level, and the federal government will be unable to pay its bills.” She also reiterated her call for Congress to swiftly boost the debt limit.

The Treasury prefers to offer date ranges as opposed to a drop-dead date. But so far that range is unworkably wide for Congress.

“It would help to have a clear and credible deadline that the Hill takes very seriously,” said Alec Phillips, chief political economist at Goldman Sachs and a former Senate Finance Committee staffer. “Without a deadline it’s going to be hard to get people to act, and right now it’s not all that clear what the deadline is.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.