Trump’s 50-Year Bond Dream Saves Little for American Taxpayers

Trump’s 50-Year Bond Dream Saves Little for American Taxpayers

(Bloomberg) -- Donald Trump’s big idea to refinance America’s burgeoning debt by selling ultra-long-term bonds, locking in historically low interest rates for a half-century or more, has never been all that popular on Wall Street.

But even if he goes through with it, there’s little chance it will actually save taxpayers much money as the deficit spirals toward $1 trillion.

The Treasury Department shelved the idea of ultra-long bonds after a tepid reception just two years ago. But it resurfaced during an economic briefing in the Oval Office on Aug. 14 -- the day that rates on 10-year U.S. debt fell below those due in two years, according to one person familiar with the matter. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and his top economic adviser Larry Kudlow suggested ultra-longs to Trump, who wanted to learn more, the person said. Two days later, Mnuchin announced the government was once again considering issuing 50- or even 100-year bonds.

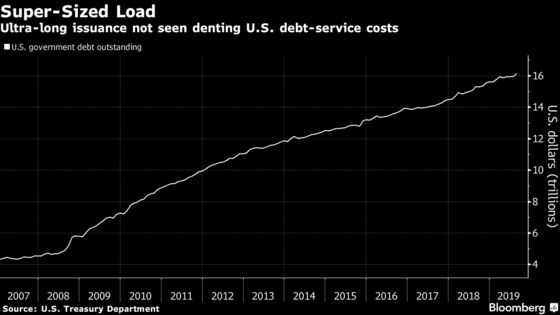

The flaws in their plan, at least among those on Wall Street, are obvious. First, with a public debt burden of $16 trillion and rising, it’s unlikely the U.S. could ever sell enough of the securities to shift the interest burden from its shorter-term obligations in any meaningful way. Second, investors would likely ask for higher yields to hold onto ultra-long obligations vis-à-vis shorter-term debt. That could easily raise -- rather than lower -- the government’s overall costs.

“This wouldn’t really move the needle,” said Praveen Korapaty, chief global rates strategist at Goldman Sachs. “So it’s questionable if it’s even worth your energy trying to potentially save -- and it’s not a guaranteed saving.”

That hasn’t stopped the administration from pressing its case. Since that August meeting, Trump has hinted at his interest in long bonds.

On Thursday, Mnuchin said he would issue ultra-long bonds as soon as next year if there is investor appetite. His team has already reached out to the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee and other market participants on the issue, and will soon do the same with foreign governments as well.

“It’s quite attractive for us to extend and de-risk the U.S. Treasuries borrowing,” he said on CNBC.

The numbers suggest that might be easier said than done.

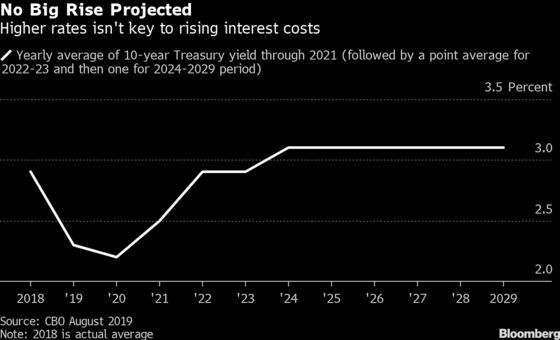

Currently, the U.S. government pays roughly $300 billion a year in net interest expenses, which includes the coupon payments on its Treasury debt. That amount is set to more than double over the next decade as Trump’s tax cuts and increased spending on Social Security and Medicare push the government even deeper into the red -- boosting its debt load by trillions.

So even if the Treasury sold $50 billion in 50-year bonds next year at a small premium to the 2.3% yield on 30-year bonds -- which some have pegged as a best-case scenario -- it wouldn’t move the needle on interest costs.

True, it would defer the need to repay that amount far into the future and avoid potentially higher refinancing costs in the short-term. But it would be a drop in the bucket compared with the over $10 trillion increase in the nation’s debt burden that the Congressional Budget Office forecasts for the next decade. That growth is the main force driving up U.S. interest expenses.

| Read more: |

|---|

|

And TBAC, a committee of large bond dealers and investors that advises the Treasury on debt-management matters, has in recent years indicated that shifting issuance more heavily to securities with maturities of five years or less is the most attractive mix to meet the government’s debt-financing goals.

Granted, “there is a rare opportunity to get low interest rates and also lower roll-over risk,” said Marc Goldwein, senior policy director at the nonpartisan budget watchdog Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “But to think that issuing ultra-long term debt is a sort of cheating way out of our fiscal problems is pretty naïve. Our interest costs are surging fundamentally because the amount of our debt is rising.”

The Treasury’s longstanding preference for regular and predictable debt issuance may also complicate matters. While there have been any number of cases in recent years of governments (see Austria, Belgium and even Argentina) selling 100-year bonds to take advantage of the global decline on borrowing costs, they’ve all been largely opportunistic one-offs.

To inundate the market with regular sales would be quite another thing. It’s one reason Wall Street predicts demand for ultra-long Treasuries would be limited and lead the Treasury to pay more in interest to attract buyers. According to a JPMorgan Chase & Co. client survey, a 50-year bond would likely yield 10 to 20 basis points more than the 30-year.

Another is the added risk of owning such long-maturing debt, prices on which are more sensitive to swings in interest rates. A small increase in yields can lead to large losses for investors on their principal. Those risks were never more clear than on Sept. 5, when optimism about the trade war drove longer-term Treasuries to their biggest intraday rout since the day after Trump’s election in 2016. Austria’s 100-year bonds also suffered losses, leading commentators to point out just how quickly gains on ultra-longs can evaporate.

Of course, nobody is doubting Uncle Sam’s ability to auction its debt, regardless of maturity. And some see good reasons for issuing longer-term debt, in particular that it reduces roll-over risk -- the chance that when the government’s obligations mature Treasury has to refinance at higher rates.

But to many observers, adding 50-year securities isn’t an effective way give taxpayers a break.

“You do have an aging population, so demand for long-term fixed-income instruments will go up over the next decade,” said Chirag Mirani, head of U.S. rates strategy at UBS. “But given that our debt outstanding is so high, even sales of $20 or $30 billion of 50-year bonds a year doesn’t give any real clear marginal gain given we have to finance a near $1 trillion deficit.”

--With assistance from Alex Wayne.

To contact the reporters on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net;Saleha Mohsin in Washington at smohsin2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Gillen at dgillen3@bloomberg.net, Michael Tsang, Mark Tannenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.