Nine Charts That Explain Trump's Battle Over Defense Spending

Trump Bump or Putin Push? NATO’s Defense-Budget Battle in Charts

(Bloomberg) -- The NATO summit that opens Wednesday is shaping up as the battle of the 2 percent, the alliance target that U.S. President Donald Trump is using to ram home his message that the U.S. gets a bad deal from allies. It’s a blunt weapon.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization set a goal for members to spend a set proportion of gross domestic product on defense at a 2014 meeting in Wales. Internally, not even NATO uses the figure as a standalone measure of what makes a good ally.

The 2 percent target “was a politically acceptable compromise” that NATO governments agreed to “so they wouldn’t have to talk about the more difficult measures,” said Kathleen Hicks, director of the international security program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank. “I don’t think it’s the real issue for Trump either -- even if all members met the target, I think he’d still be pressuring them.”

As he left for Brussels, Trump again linked low NATO spending by allies to his bigger concern over the trade surpluses they run with the U.S. “Not fair to the U.S. taxpayer,” he tweeted.

One problem with the 2 percent target is math: It’s as dependent on shifts in economic growth as it is on changes in defense spending. German officials, for example, say that in the 10 years to 2024, the country will have added 80 percent to its defense spending despite only inching a few basis points to reach 1.5 percent of GDP. Yet by 2024, Germany would be spending about as much on defense as Russia does today. By the same token, China has vastly increased its defense spending to $228 billion since 1990, but the share of GDP has barely moved.

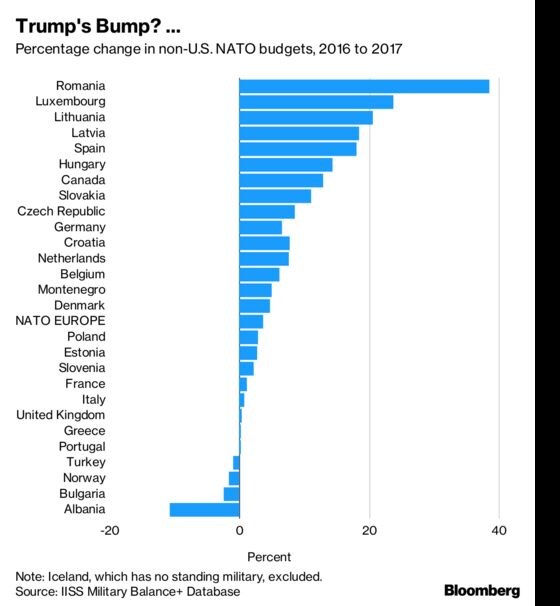

Defense budget increases in inflation-adjusted dollars would make a more reliable measure of higher spending. On that score Trump could, if he wanted, claim credit for a significant boost last year. Romania was a standout, spending 38.6 percent more in 2017 than 2016. For Germany, Trump’s main whipping post, that number was a healthy 6.6 percent. For two of the three tiny Baltic States it was over 20 percent.

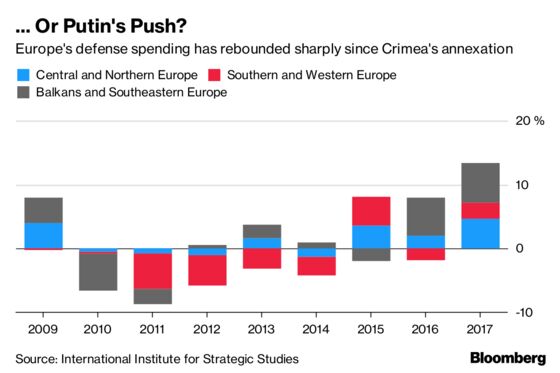

Those increases probably had as much to do with fear of Russia and a recovering European economy as Trump. The trend began long before he took office:

No one in Brussels is likely to begrudge the U.S. president a win if he wants to take it; anything to avoid another bust-up like last month’s G-7 summit in Canada. But judging by the letters and tweets Trump fired off ahead of this week’s meeting, he seems unlikely to take the high road.

Few European governments dispute that they need to do a lot better. Some came close to effective disarmament after the end of the Cold War. Germany may already spend about $40 billion a year on defense, but it gets little combat-ready capability for the money. Yet that isn’t something the 2 percent target will necessarily identify or fix.

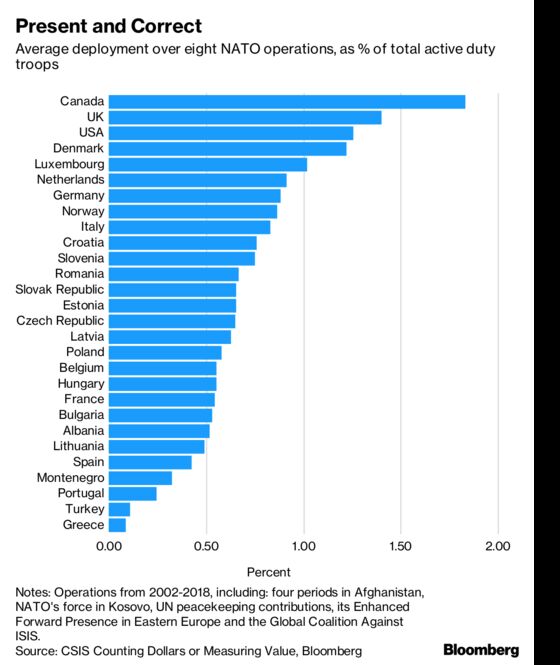

What if a country spends less but better, making it able to deliver troops, naval vessels and aircraft able to operate alongside U.S. forces? Or is more willing than others to actually deploy troops to fight? Or builds better infrastructure for NATO forces to cross its territory in the event of war? Or pays for training and force building in failing states? None of this would be captured by the current target.

NATO has a published secondary measure, for the proportion of national defense budgets spent on equipment. Greece, for example, exceeds the 2 percent spending goal, but fails on equipment. Almost three quarters of its budget goes to paying salaries and pensions that can’t be deployed to any battlefield. That, however, just deals with one failure of the GDP target.

This doesn’t reflect the absolute scale, or the quality of contributions. Some countries, including Canada, France, the Netherlands and the U.K., sent their troops into combat in Afghanistan. Germany, burdened by its World War II history, restricted what its forces could do. Still, relative to the number of active duty troops that countries have, the chart indicates how willing they have been to show up when called.

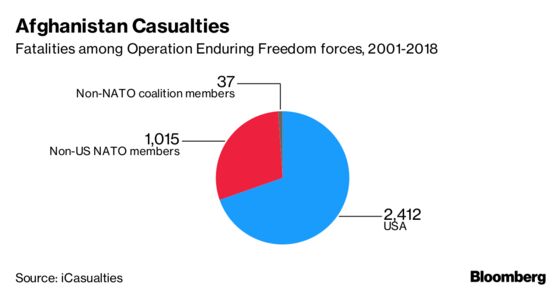

And it isn’t as though even German soldiers faced no risk; 54 lost their lives in Afghanistan since 2001. About 30 percent of coalition casualties -- in an operation called to aid the U.S. after the September 11, 2001 attacks -- have been suffered by non-American troops. The U.K., with 455 dead, suffered almost as high a casualty rate relative to its population size as did the U.S.:

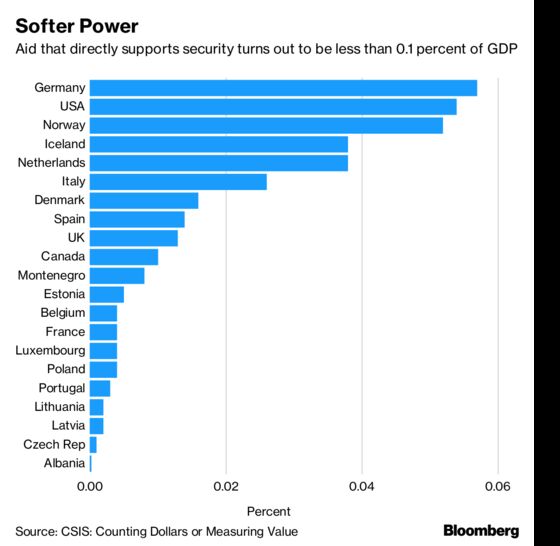

Germany has argued that softer aspects of providing security such as development aid should be included in defense spending (that would get Berlin over the target at a stroke of a pen). The CSIS team didn’t agree, but they came up with a definition of assistance that does contribute directly to security. Germany came out top:

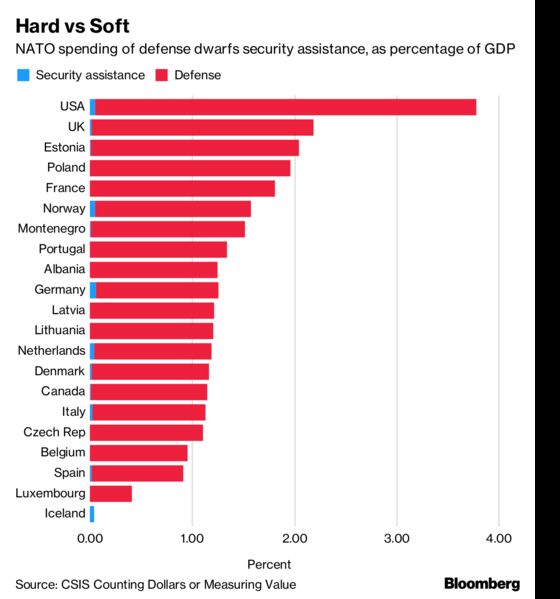

But defined by the CSIS report, these “soft” expenditures on security assistance are negligible. Now take a look at them (in blue) next to the “hard power” budgets (in red):

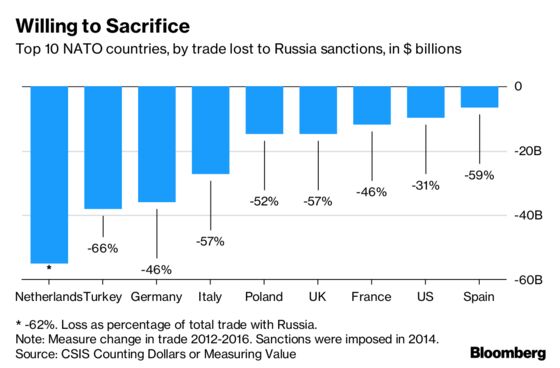

Other measures the CSIS team chose would be controversial if proposed at NATO, especially where the current White House is concerned. One looks at the trade sacrifices countries made to enforce sanctions against Iran (where Trump might agree this should count as a contribution to security), and Russia (where he might not). Here’s what happened to trade with Russia as a result of sanctions imposed after its 2014 military interventions in Ukraine:

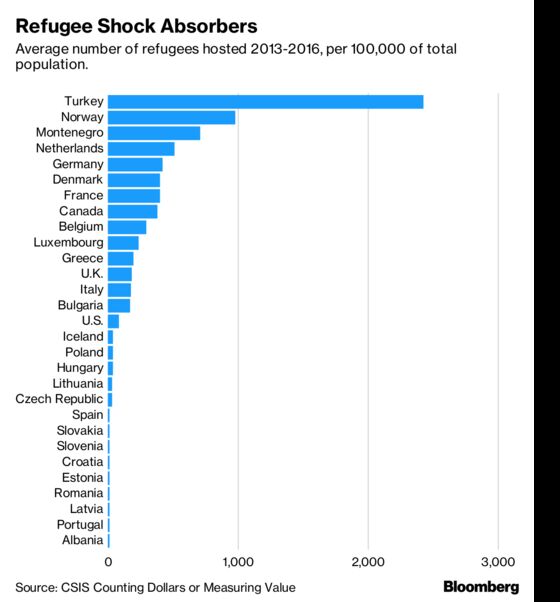

Almost certainly, Trump would take issue with another CSIS criterion: The willingness of NATO members to accept refugees from conflict zones. It’s a complex argument, but suffice to say that Turkey’s willingness to host more than 3 million refugees from Syria has made a contribution to the security of European NATO members further West (and one the European Union pays Turkey to continue):

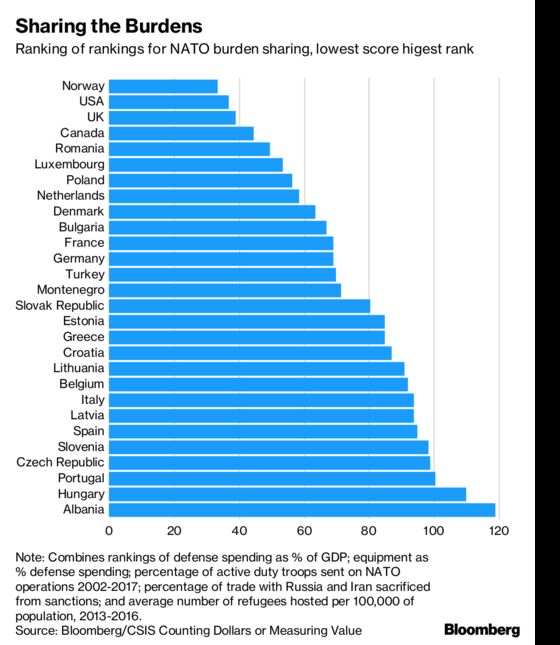

So who are the best alliance members? It’s a hard question to answer, but it’s pretty clear that Greece isn’t number two to the U.S. -- as it would be in terms of defense spending as a percentage of GDP. CSIS is pushing NATO to publish its classified benchmarks to make the issue more transparent and balanced.

In the meantime, here is an unweighted ranking of where allies stand on the combined published NATO and CSIS benchmarks, compiled by Bloomberg. It is wholly unscientific, though perhaps no less flawed than the 2 percent target that is monopolizing NATO debate:

--With assistance from Patrick Donahue.

To contact the reporter on this story: Marc Champion in London at mchampion7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Alan Crawford, Richard Bravo

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.