Treasury’s 20-Year Reboot Drives Troubleshooting Across Curve

Well Fargo forecasts that when the 20-year is fully up and running, Treasury will sell about $39 billion quarterly.

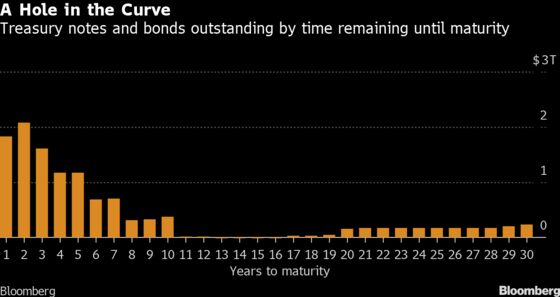

(Bloomberg) -- The U.S. Treasury’s plan to reboot its 20-year bond clarified how the government will fund a $1 trillion deficit, but also raised questions about the decision’s ramifications elsewhere in the market.

Traders took a stab at providing some answers in the immediate aftermath, reshaping the yield curve. The extra yield on 30-year bonds versus 2-year notes rose almost 3 basis points on Friday, the biggest increase since late December.

While some see this move auguring a steeper curve longer term, much will depend on how the Treasury Department rejiggers its lineup of issuance. And that in turn will depend on when the sales begin, and their size, analysts say.

Wall Street dealers seem generally of the view that the new issue will lead to only marginal cuts, if any, to other coupon-bearing auctions. At UBS, strategist Chirag Mirani says the market pricing has already adjusted to the prospect of new supply, and he sees the recent cheapening in longer-dated Treasuries as a buying opportunity.

But Jim Caron at Morgan Stanley Investment Management sees cuts closer to the front end of the curve, which should help widen the gap between short- and longer-end yields.

“We like the curve steepener, so this is a welcome thing,” Caron said Friday.

| More Coverage of Treasury Issuance |

|---|

|

Most dealers anticipate the new 20-year bonds to debut in May. Waiting until around mid-year reduces the need to shave auction sizes that are historically large, which has left the Treasury well-funded for now.

But the federal budget deficit is set to surpass $1 trillion, and the U.S. also has to deal with a wall of debt starting to mature later this year. As a result, any move to shrink offerings of other coupon-bearing maturities to make room for the 20-year would soon have to be reversed. And if the Treasury does take that step, bills are seen as the most likely candidate.

“The key reason for Treasury to introduce the 20-year now is that it gives it a warm-up period,” said Jim Vogel, a strategist at FHN Financial. “It will be absolutely necessary later on for larger auction sizes overall,” so cuts now would only be temporary.

For decades, the Treasury has sought a regular and predictable approach to issuance, which it sees as fostering investor demand and reducing the cost to taxpayers. That approach has meant that officials prefer not to make abrupt or frequent changes to their auction slate.

One reason to expect a supply-driven steepening in the curve is looking shakier: The decision to reboot the 20-year, which the U.S. stopped issuing in 1986, appears to put on ice for now the prospect of even longer maturities. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has been pondering that step since he took over in 2017. The 20-year idea seemed to gain traction last quarter.

There’s another key reason analysts say the Treasury can wait a few months to introduce the two-decade maturity. Its financing position is getting a boost from the Federal Reserve’s monthly purchases of $60 billion in T-bills, a program aimed at increasing reserves. As those securities mature and the central bank rolls them over, it reduces the amount the government needs to borrow from the public.

“Based on the current auction sizes and projections for the deficit, it seems unlikely to us that Treasury will start issuing the 20-years in February, but they will likely announce in May the actual start of sales,” said Zachary Griffiths, a rates strategist Wells Fargo Securities. “And at that time, Treasury could start 20-years a bit smaller than its full annual run-rate plans, or if not, just cut the 30-year auctions by a few billion.”

It will likely leave the 10-year alone, because its role as the world’s borrowing benchmark means it needs to be highly liquid, according to Griffiths.

Well Fargo forecasts that when the 20-year is fully up and running, Treasury will sell about $39 billion quarterly, or about $150 billion to $160 billion each year. The Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee has recommended that the government issue $140 billion annually.

More information on the 20-year will come at Treasury’s next quarterly announcement of longer-dated debt sales, on Feb. 5, the department said in a statement. In its regular quarterly survey released Friday, Treasury asked dealers about the maturity, including their view on the minimum auction size and total issue size necessary to ensure benchmark liquidity.

“Treasury will likely do this in a way to limit adjustments needed in other coupon maturity sizes, or even prevent any from occurring at all,” said Mark Cabana, head of U.S. interest rates strategy at Bank of America Corp.

--With assistance from Saleha Mohsin and Elizabeth Stanton.

To contact the reporters on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net;Emily Barrett in New York at ebarrett25@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Nick Baker, Mark Tannenbaum

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.