The Money Taboo That Central Banks Have Shied Away From So Far

Governments paying for budget spending with loans from their own central banks is known as monetary financing, a slippery slope.

(Bloomberg) --

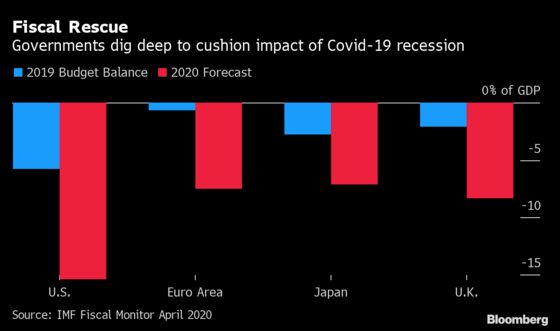

The coronavirus economy is shredding records for government borrowing and for central-bank lending. Soon it may also smash the taboo that’s supposed to keep those two things apart.

Governments paying for budget spending with loans from their own central banks is known as monetary financing. The risk, repeated throughout history from the Weimar Republic to parts of Latin America, is that it becomes a slippery slope in which politicians ride roughshod over central-bank independence, triggering runaway inflation as they splash what feels like free cash around the economy.

The stricture against direct financing has held up even through a series of crises when central bankers did in fact buy plenty of public debt. They just made sure to do it in a roundabout way, snapping up bonds in the secondary market.

But in a pandemic that’s placing unprecedented demands on budgets -– and could strain the capacity of bond markets to finance them -- some monetary experts say it’s time for exactly this kind of break-the-glass policy.

“Independence doesn’t mean having to say no to a request for direct monetization,” says Willem Buiter, a former Bank of England policy maker and Citigroup chief economist. “It means you can say yes or no.”

Government Overdraft

Right now, according to Buiter, the answer that makes sense in developed economies is ‘yes’.

As they pour money into the virus fight, policy makers “needn’t bother with the sovereign debt market,” he says. In what would amount to cutting out the middleman, central banks can just buy debt direct from governments “or simply credit the treasury’s account.”

Last week, the Bank of England appeared to be doing something like the latter -– triggering a flurry of interest among central-bank-watchers -- when it extended an overdraft to the government.

Just days earlier, Governor Andrew Bailey had appeared to rule out the use of monetary financing, after a former BOE deputy chief had urged the bank to buy bonds directly from the government.

The overdraft facility has been drawn on before, in wartime and most recently after the 2008 crisis. It’s a temporary measure, according to U.K. officials.

‘They’ll Do It’

But the recent history of monetary policy is full of stopgap moves introduced during a crisis that turned out to be hard to reverse. And they’ve tended to leave government and central-bank finances more closely entwined.

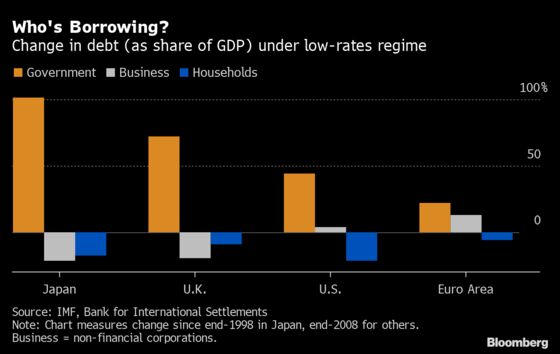

Japan’s central bank, for example, started amassing government bonds two decades ago to break the grip of deflation. Now, it has a balance sheet bigger than the economy, owns some 43% of the government’s outstanding bonds, and has seen its policy of quantitative easing replicated across the industrial world.

“The Bank of Japan started down this road in the late 1990s, and we’ve all been following their example,” said Russell Jones, a partner at London-based research group Llewellyn Consulting. “It’s been a progressive shift. We’re moving towards overt monetary finance.”

That barrier may be breached soon, he said. If economies continue to deteriorate because of the pandemic, “you will see central banks directly financing governments, they’ll do it explicitly, it’s only a matter of time.”

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say...

‘Back in the great financial crisis, central banks could legitimately argue that asset purchases were the pursuit of monetary policy by other means -- bringing down longer-term borrowing costs to stoke private-sector borrowing.

In 2020, that fig leaf isn’t there. We’re not quite at monetary financing of fiscal deficits. Still, the main beneficiary of central bank purchases will be governments.”

-- Tom Orlik, chief economist. Read the full piece here.

The longstanding fear has been that handing this kind of money-creating power to politicians with short-term electoral goals will lead to over-spending that hurts economies in the longer run by fanning inflation.

That’s why most developed countries keep those levers in the hands of central banks with some autonomy from the rest of government. It also explains why some analysts are alarmed that the current spending spree could ultimately send prices surging, creating bigger problems for central banks down the road.

But most argue that in the immediate future, at least, the bigger risk is deflation as the virus destroys businesses and jobs and hammers demand.

‘Same Drum’

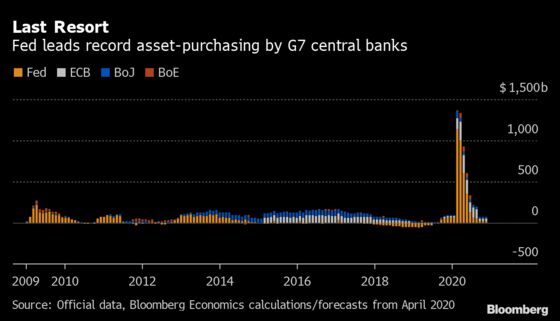

The lines that separate overt monetary financing from other kinds of central-bank support for governments aren’t clear-cut. In the U.S., for example, the Federal Reserve doesn’t buy government debt directly from the Treasury, but it’s bought plenty via QE since 2008.

And this year, with the Treasury issuing trillions in bonds at an unprecedented pace, the Fed is set to hoover up more than 90% of them, according to Bank of America projections. It just won’t be doing so directly at Treasury auctions.

The upshot isn’t that different from direct monetary financing, according to Buiter. But “the statement is more powerful,” he says, “if the Treasury and Fed are visibly and audibly banging on the same drum, not being coy about it, recognizing that they are monetizing fiscal action.”

Advocates of Modern Monetary Theory, an emerging school of economics, also play down the idea that there’s anything scary about such arrangements. MMTers say the question of whether spending is financed by treasury bonds or central-bank reserves isn’t a big deal -- since both are government liabilities in the end. What matters is whether the spending triggers inflation.

The increasing role of asset purchases, and the blurring of lines with fiscal policy, has come about as central banks ran out of other ways to stimulate.

There was no room left to cut the cost of credit for households and businesses, so that they’d take on more debt and spend or invest. Instead, governments took over as the main borrowers, and became the chief beneficiaries of the super-low rates -- starting in Japan, the first country to get to zero.

And in a bad scenario where the global economy struggles to shake off Covid-19, economists at Evercore ISI wrote last week, the Japanese combo of persistent fiscal support by the government and asset purchases designed to keep borrowing costs low “is a plausible end-destination for much of the world.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.