Gig Economy Isn’t Solving Eastern Europe’s Brain Drain Problem

The Future of Work Is Here and Europe’s Fringe Isn’t Ready

(Bloomberg) --

The new age in the labor market is shaping up as a missed opportunity in the poorer parts of Europe to stem the outflow of skilled labor.

Hundreds of thousands of Serbians, Ukrainians and Romanians make a living through global freelance platforms, working for international clients that pay better than local companies. It could be a perfect way to keep the best minds from leaving their homelands for better opportunities abroad. Instead, outdated regulations force them to live on the edge of legality, and may foil efforts to slow the brain drain.

Eastern Europe for centuries has been defined by a desire to catch up with the West. In the past three decades, post-communist countries have transformed their economies and became part of global supply chains. Now the rise of the gig economy offers a chance to take another leap. But the generation that’s grown up since the end of the Cold War is being dragged down by some of Europe’s most corrupt political systems.

“This is the moment, just like in Star Wars, when ships make the jump” through hyperspace “from one system to another,” said Branka Andjelkovic, a co-author of Digging Into the Gig Economy in Serbia. “If you want your economy to advance and to have those people stay here, then do something.”

It’s already too late for some, like Mateja Miladinovic, a 34-year-old graphic designer in Belgrade. After more than two years as a freelancer, he’s moving to Bali with his wife for a change of lifestyle with less stress from Serbian authorities. The constant pressure of an uncertain tax status within the Serbian system and a lack of access to social, health and retirement benefits were enough to convince him to leave his homeland.

“I’m in a gray area,” said Miladinovic, who does magazine layout work for clients from Canada to Ethiopia. He expects to continue the same jobs from his new tropical home.

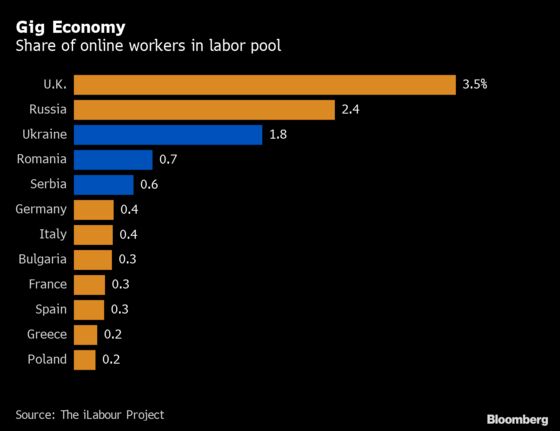

Serbia, along with Ukraine and Romania, is in the vanguard of the gig economy in eastern Europe. The jobs are mostly in technology, graphics, Internet design and media and not necessarily in ride sharing or food delivery that are the hallmarks of the industry, partly because of historically low wages compared to the rest of the continent.

They are also among the region’s most unstable politically, which has led to inaction on updating rigid communist-era regulations. Another common thread is widespread graft: Romania ranks 61st, Serbia is 87th, and Ukraine is 120th in Transparency International’s annual corruption perception index.

Many western economies already had higher levels of protection and more flexible labor codes when the gig platforms started popping up. And they are going further: the U.K., for example, last year proposed legislation to increase protections for freelancers.

California this month passed a bill that could force companies to reclassify gig workers as employees, a move that would secure labor protections. The legislation is emblematic of the debates in countries from Germany to the U.S., which are about defining the industry and regulating employer-employee relations, rather than about the legality of gig work.

The good news is that Ukraine, Romania and Serbia have an abundance of high-skill workers in technology. Many of them work remotely, which so far has slowed the brain drain, according to Janine Berg, a senior labor market specialist at the International Labour Organization in Geneva.

And the prospect of becoming their own masters as part of a global workforce with seemingly endless opportunities remains seductive.

“Every young person that doesn’t have a job wants to be a freelancer, they want to travel the world and still be able to work,” said Belgrade-based tax expert Sofija Popara. “It’s a short-term plan, but young people are doing it more and more.”

But the warnings are becoming louder. Romania needs a “redefining and reform of work relations,” according to a European Commission-financed study by the Institute for Public Policy. In Ukraine, the ILO last year urged “policy responses that can enhance the benefits of the work transformation.”

The International Monetary Fund in a July study warned that countries in eastern Europe need to do more to “retain and better use the existing workforce” to combat what threatens to become a significant drop in population driven in part by outward migration.

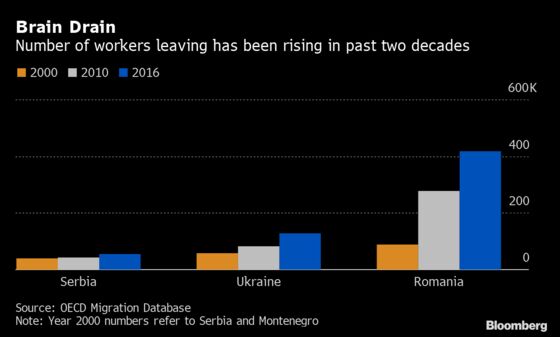

Brain drain is a common problem for Romania, Ukraine and Serbia. It contributed to 600,000 people from the three countries combined leaving in 2016 for better jobs and life prospects around the world. That’s three times more than the outflow in 2000, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Serbia hasn’t addressed freelance workers in the labor code and the ministry hasn’t responded to questions from Bloomberg. Ukraine allows them to register and pay taxes at a favorable rate, but no protections. The new government this month promised changes by the end of the year.

And while Romania is required to incorporate European Union legislation, the work has been slow amid near-constant political turmoil. The labor ministry in Bucharest said it’s working on implementation, with a deadline of Aug. 1, 2022.

Even the highly skilled and technically savvy gig workers are vulnerable in the cutthroat competition for contracts. The lack of other opportunities means they have little leverage against faraway employers.

“Freelancing isn’t an easy life and it’s definitely not for everyone,” said Jelena Novakovic, a graphics designer in Belgrade who works for clients typically in the U.S. or Australia.

Some gig workers are trying to take control of the process. Tamara Gavric, a Belgrade architect, has also become an activist for promoting safer freelance labor. The lack of state protection is draining the profession even as it becomes more prevalent in the global workforce, she said.

“The situation has to be resolved because we do not want to be underground workers,” Gavric said.

Online platforms collect as much as 20% on jobs and offer little comfort to workers. A third of Ukrainian freelancers in a recent survey complained about non-payment with no recourse.

“If the platform is going to arbitrate, they usually go with the side of the company,” Berg said. “There’s no regulation at all and you have oversupply, so there is a tendency for wage rates to fall.”

Serbian gig workers are arguably the worst off. Without legal recognition, they are considered jobless, which can make taking out a mortgage or a credit card impossible. The only option is to register as self-employed entrepreneurs, which often means an immediate 40% tax rate.

One option, of course, is trying to find a traditional job with a local company. But for Miladinovic, the magazine designer, that was never going to be the way out.

“I still can’t imagine a permanent position with a company,” he said. “For the time being I can see myself only as a freelancer and depending on cash flow, we’ll see.”

--With assistance from Irina Vilcu, Daryna Krasnolutska and Peter Laca.

To contact the reporters on this story: James M. Gomez in Prague at jagomez@bloomberg.net;Gordana Filipovic in Belgrade at gfilipovic@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Balazs Penz at bpenz@bloomberg.net, Andrew Langley

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.