(Bloomberg Markets) -- If you’re seeking the key to the euro zone’s economic outlook, all roads lead to Rome.

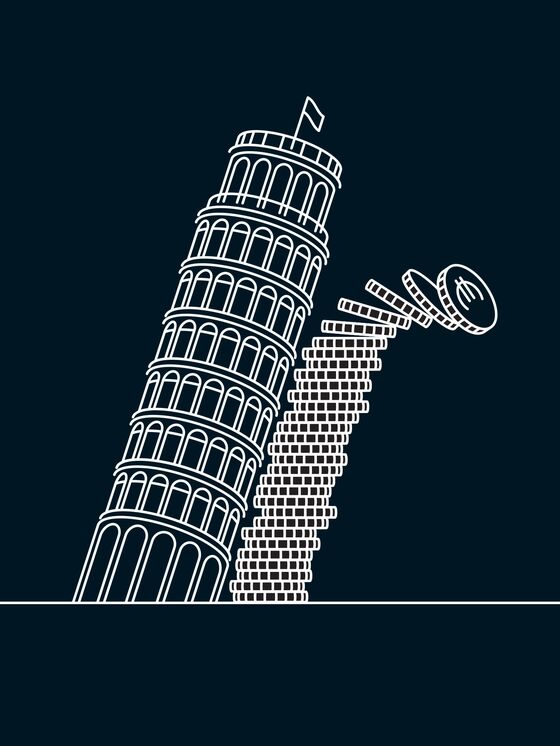

Italy’s public debt of €2.4 trillion ($2.7 trillion) is significantly bigger than its economy and among the largest in the currency union, making it the most dangerous. This debt mountain threatens the financial stability of Italy and the future of the euro: Any plans to strengthen the single currency must solve the question of who will bear this burden.

For centuries, it was bankers from the Italian peninsula who helped foreign states handle their finances. Luca Pacioli, a Tuscan-born Franciscan friar, is widely considered the father of modern bookkeeping thanks to his work on the double-entry system. The Medici lent extensively to royalty across Europe, including the French and the English. In 1340, King Edward III of England defaulted on loans received from Italy to fight France in the Hundred Years’ War, bankrupting the Bardi and Peruzzi banking families.

Fast-forward to the late 20th century, and Italy became the borrower rather than the lender. In the 1970s and ’80s, the country’s public debt skyrocketed, soaring from 36 percent of gross domestic product in 1969 to 121 percent by 1994. In those two and a half decades, Italian leaders increased public spending substantially, leading to a sharp jump in interest payments, while tax revenue failed to keep up. Throughout the ’80s, Italy’s yearly budget deficit was rarely below 10 percent of GDP. Even worse, this borrowing binge failed to spur any exceptional growth.

In the past quarter century, Italy has struggled to reduce its debt. After a string of administrations managed to shrink it to about 100 percent of GDP by 2007, the Great Recession, the euro zone sovereign debt crisis, and the ensuing phase of very sluggish recovery drove Italy’s liabilities to more than 130 percent of GDP.

The contrast with Belgium is striking: In 1993 public debt there stood at 138 percent of GDP, higher than Italy’s. In 2017 it had fallen to 103 percent, below Italy’s 131 percent. Politicians in Brussels ran bigger primary surpluses—that is, budget surpluses before interest payments—than Italy while producing higher growth rates, notes André Sapir, an economist at Brussels-based economic think tank Bruegel. When the euro zone crisis struck in the early 2010s, Belgium had sufficient credibility in the bond market to borrow more cheaply than Italy.

Under the leadership of Rome native Mario Draghi, the European Central Bank introduced a program of quantitative easing in 2015 that’s helped Italy substantially. Yields fell steeply, producing enormous savings for the government. Public debt stabilized, but once again, politicians missed the chance to reduce it, preferring to cut taxes instead.

June’s formation of a populist administration has renewed concerns about Italy’s debt. During the electoral campaign, the right-wing League and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement flirted with the idea of leaving the single currency altogether. After forming a government, they agreed on a plan that included steep tax cuts, a reduction in the retirement age, and an income support program. In the fall the European Commission rejected the government’s initial budget, forcing it to submit a new draft. Italy’s 10-year bond yields climbed to the highest in four and a half years, exceeding 3.5 percent.

The government backed down, partially reassuring investors and sending bond yields well below 3 percent. But investors in Italian debt are still demanding a substantial premium over the yields on Spanish or Portuguese obligations, which have traditionally paid more. Italy entered a recession in the second half of 2018, making it almost certain that Rome will miss its 2019 fiscal targets. The country faces the prospect of a contractionary budget in the fall, which could further slow growth.

A new wave of turmoil around Italian sovereign debt remains a distinct possibility. Any fresh crisis would hit Italian banks, which have resumed loading up on their country’s debt. If bond yields were to rise sharply, weaker banks could be forced to raise new equity. Alternatively, they may decide to shed assets to preserve their capital ratios. This would squeeze lending and harm the economy, feeding a vicious circle.

The rest of the euro zone has made it clear that if Italy falls into a crisis alone, the country would need to apply for a rescue before it could receive any help. This would impose a strict set of conditions, including budget austerity and structural reforms. Some within Italy’s populist ruling coalition hope the size of the country’s debt will force the ECB to intervene to appease markets. They hope they can de facto kidnap the central bank and form some kind of alliance with it. Stockholm syndrome becomes Rome syndrome.

This is unlikely. The ECB has rules it must obey before rescuing any member state, including requiring a program of fiscal consolidation and reform. The Italian economy would be hit hard in a crisis, which would likely prompt politicians to take action before the central bank.

Still, it would be delusional to imagine that the euro zone can simply brush aside Italy’s public debt as it tries to steady the economy. The ECB has already delayed normalizing its monetary policy, which has been accommodative since 2011. A crisis in Italy, the currency union’s third-largest economy, would affect confidence across the region, limiting the central bank’s ability to hit its inflation target. Ultimately, the sustainability of Italy’s public debt could be a crucial constraining factor when central bankers decide how much and how quickly they want to raise interest rates.

Italy’s public debt will also affect the euro zone’s ability to become more resilient against any crisis. The currency union needs to complete its banking union, setting up a joint deposit guarantee scheme. It must develop some form of common budget, which can redirect money to countries facing an isolated shock. Finally, it must develop a safe asset, which banks can purchase alongside traditional securities such as German bunds.

All of these debates hinge on developments in Southern Europe and in Italy in particular. Northern European countries, including Germany and the Netherlands, demand that banks reduce their exposure to domestic sovereign debt before the euro zone can agree on a common safety net for all depositors. There is no economic reason for this sequence: All banks, including Germany’s, would benefit from a joint safety net now. But politically, it’s hard to see any progress if Italian banks continue to hold large quantities of government bonds.

Similarly, it’s illusory to imagine other countries agreeing to any form of debt mutualization unless Italy makes significant progress in reducing its own. A task group at the ECB has tried to construct a safe asset that doesn’t require debt sharing, but this project has stalled. A commitment to cut Italy’s debt would also appease fears that the country could abuse a joint budget—paving the way for some form of fiscal union.

The euro zone’s future is therefore largely dependent on Italian politicians. If they fail to reduce the public debt, the euro area will remain a halfway house, overly vulnerable to crises. Alternatively, courageous steps from Rome would make it much harder for politicians in Berlin and other key euro zone constituents to refuse to complete the monetary union. Just as in the time of the Medici, Europe’s financial future depends on Italy. Let’s hope for a new Renaissance.

Giugliano writes about European economics for Bloomberg Opinion in Rome. This column doesn’t necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Christine Harper at charper@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.