Is Iran’s Revolution Having a Mid-Life Crisis?

Stop on the Third Floor for Designer Shoes – And the Revolution

(Bloomberg) -- Builders of the gleaming glass and stone Iran Mall that’s nearing completion on Tehran’s north-western edge say it will be the Middle East’s biggest, required the world’s longest ever continuous cement pour and will “revolutionize retail life in Iran.”

Shopping was not the revolution Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had in mind when he returned from exile to overthrow Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi 40 years ago. Yet Tehran’s unfinished mega mall showcases the fragilities that have come to challenge a system underpinned as much by promises to deliver prosperity and fairness as religious orthodoxy.

The government ended 10 days of celebrations for the 1979 revolution on Monday, holding public rallies across the country – including Tehran’s Azadi square, scene of the protests that brought down the Shah four decades ago. Pop bands played songs celebrating the revolution from stands lining the streets and hawkers sold balloons for children.

“This year we are holding the celebrations at a time when we face conspiracies by the criminal U.S. and the Zionist regime,” President Hassan Rouhani told the gathering, in an uncharacteristically passionate, hard-line speech. Iran’s path, he said, will “continue the same way it has for 40 years.”

The crowd, as usual, consisted mainly of conservatives and women dressed in the chador, a black full-length cloak. This time, though, their placards read “No to Embezzlement,” “No to Profiteering,” and “No to Aristocracy” rather than slogans against the 2015 nuclear deal with international powers that were prevalent in recent years.

But the organized fist-pumping and show of unity among ruling factions couldn’t mask growing popular anger over the cronyism, corruption and inequality that have come to burden the Islamic Republic at least as much as U.S. sanctions.

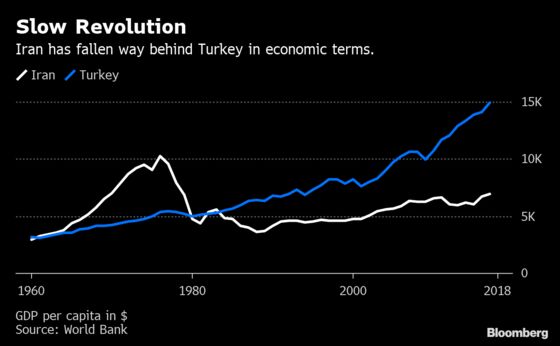

In some areas, the revolution delivered. Iranians now have better access to health and education, particularly in the country’s provinces and rural areas. They can also expect to live as long as some nations in Europe. Literacy rates have soared, more than tripling for women. The economy, however, has pedaled backward relative to Iran’s peers.

Four decades ago, Iran and Turkey had roughly the same size economies in dollar terms. Iran’s is now just over half the size of its neighbor’s while the countries have similar populations.

A long war with Iraq and trade embargoes quickly followed the revolution and the Iranian oil and gas industry never returned to the peak levels of output under the Shah. Banks and the services industry, meanwhile, have been starved of capital.

“Wrecked by revolutionary turmoil and ravaged by years of war, sanctions and mismanagement, the Iranian economy has failed to fulfill its enormous potential, squandering the prosperity of an entire generation of Iranians,” said Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the Brussels-based International Crisis Group.

The clerics running the country since 1979 still exert a vice-like grip on power that shows no sign of slipping. Yet as inflation ate away at meager salaries and renewed U.S. sanctions squeezed oil revenues last year, a slew of protests in gritty provincial towns signaled that faith in the ability of the Islamic Republic to turn the economy around may be declining.

Selling the revolution’s virtues is only likely to get harder. Already, almost 70 percent of Iran’s population was born after the Shah’s fall and has no direct memory of the monarchy’s injustices.

Debate within the regime over how to reform the economy – and so preserve the revolution – is intense.

President Rouhani wants to see state institutions such as religious foundations, or “bonyads,” pay tax and he’s signaled that bodies such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. should avoid commercial enterprises that crowd out private investment. Rouhani was also the driving force behind the 2015 nuclear deal with major world powers, aimed at lifting sanctions so Iran could integrate into the global economy.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei advocates the construction of a “resistance economy,” isolated enough to be immune to external shocks. His concern, according to Vaez, is that too much economic liberalism and opening to the West could weaken the regime’s authority.

On Feb. 7, the speaker of Iran’s parliament said Khamenei had issued instructions to implement new “structural reforms” in the national budget, though it wasn’t clear what they would entail.

The sacrifice required to defend the revolution is a tough sell to a population that can see the children of the elite driving sports cars, shopping at flashy shopping malls and boasting on Instagram about their expensive designer clothes.

The regime is trying to respond. The judiciary, also led by clerics, has been cracking down on “profiteers,” the short-sellers and businessmen who managed to enrich themselves by brokering deals that evaded sanctions and exploited Iran’s currency crisis. At least three people have been hanged since the effort started last summer.

The Islamic Revolution Mostazafan Foundation, set-up by Khomeini to manage assets seized from the Shah and his supporters, announced in August that it would stop developing luxury buildings and malls. The Foundation has become one of the biggest conglomerates in Iran.

Meanwhile, a former chief executive and board member of another private bank, Bank Sarmayeh, are on trial for embezzlement, together with a former government minister. Prosecutors allege that 94 percent of the loans the bank paid out were suspicious and never repaid.

“The banking system is the heart and center of corruption in Iran, and this predates the Islamic Republic,” said Saeed Laylaz, an economist and former adviser to reformist President Mohammad Khatami.

Banks used by politically connected businessmen to lend to themselves is a problem that Russia, Ukraine and other nations have also had to clean up. But the Iranian revolution promised a more fair and less corrupt society.

Indeed, Iran Mall, still under construction after seven years, is a monument to how cronyism damaged the banking system, hobbled the growth that might have been achieved even under sanctions and undermined the claims of the revolution.

Covering 2 million square meters of land, more than half of New York’s Central Park, the project was among dozens of shopping malls and luxury developments started in Tehran during the populist presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad between 2005 and 2013. Soaring oil revenues and lax regulation allowed banks to enrich their own subsidiaries with billions of dollars of loans.

The Iran Mall Development Company hasn’t published a project cost. The Fars News agency reported last year that Ayandeh Bank had by 2017 loaned 220 trillion rials ($7.6 billion at the official exchange rate of the time) to the company, which was a subsidiary of the bank and has two other big malls under construction, according to its website. The Fars report was removed from the news organization’s website a day after publication.

Last month, Ayandeh Bank announced plans to divest almost all of its stake in the mall development. Chief Executive Jalal Rasoulof said the measure was in line with Central Bank of Iran’s policy of requiring lenders to divest their holdings in companies they lend to, according to the Iranian Students’ News Agency, another semi-official outlet. Iran has 35 licensed financial institutions and the central bank wants that number reduced.

In January, rumors swirled across social media that the bank’s chairman, the industrial magnate Ali Ansari, had fled Iran with billions of dollars. Ansari quickly made a public appearance in Tehran. The central bank published a statement denying that Ayandeh Bank was at risk of collapse.

Rasoulof’s office referred requests for an interview to the bank’s public relations department, which did not respond to requests for comment. The head of public affairs for the Iran Mall Development Company canceled a meeting to discuss the project and did not respond to written questions from Bloomberg.

“Right now something like the Iran Mall could not be repeated – no bank would be able to start something like this and this shows Iran is slowly moving in the right direction,” said Laylaz, the economist. Still, he added, when it comes to the economy, the revolution “has a very, very long way to go.”

--With assistance from Ladane Nasseri.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Benjamin Harvey at bharvey11@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.