South Korea’s Moon Faces Crisis With Echoes of Park’s Downfall

Moon was forced to issue a public apology Monday after his justice minister Cho Kuk, bowed to mass protests and resigned.

(Bloomberg) -- Three years ago, South Korea’s Moon Jae-in was among the masses in the streets of Seoul seeking to oust a president accused of ignoring the people’s will. Now, his own presidency is facing a similar crisis.

Moon was forced to issue a public apology Monday after his justice minister and political ally, Cho Kuk, bowed to a series of mass protests and resigned. The departure represented a stunning setback to Moon, who had only five weeks ago ignored corruption probes swirling around Cho and his family to put him in charge of the country’s justice system.

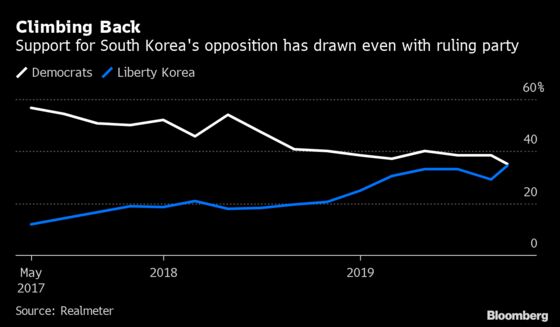

The demonstrations and investigations have only intensified in the intervening weeks, with Cho’s home raided by prosecutors and lawmakers shaving their heads to protest the appointment. The conservative opposition -- struggling since Moon helped impeach former President Park Geun-hye in 2016 -- has climbed level with the ruling Democratic Party in opinion polls.

“The circumstances that brought down former President Park Geun-hye and started Moon’s administration are now bringing him down,” said Hong Sung-gul, a professor with Kookmin University’s Department of Public Administration. Moon and Cho “thought that pushing the criticism to the side would somehow make this go away, but it didn’t and it developed an even stronger opposition,” Hong said.

The shift has increased the political peril for Moon just as he begins to prepare for nationwide parliamentary elections in April. The episode shows that Moon, a former civil rights lawyer, hasn’t broken the boom-and-bust cycle of South Korean presidents, who often see scandals mount and agendas stall in the second half of their single five-year term.

Justice Ministry officials were due to appear in parliament Tuesday to face questioning over Cho’s plans to reform the national prosecutors’ office, with the conservative opposition set to blast Moon for his decision to appoint his close confidant as minister.

Moon told a meeting of top secretaries Monday that he felt “quite regretful” for having “caused so much friction between the people.” He then took a swipe at the press, urging the country’s free-wheeling media to become more “trustworthy,” without elaborating.

Moon already faced headwinds on two of his biggest agenda items: Reinvigorating the economy and securing peace with North Korea. South Korea’s central bank has warned that the economy may not meet its 2.2% growth target this year and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has resumed ballistic missile tests and mocked Moon’s efforts to mediate nuclear talks with President Donald Trump.

People Power

Meanwhile, Moon’s government and Japan have escalated a nationalistically charged feud, putting pressure on both their economies and drawing rebukes from the U.S. Moon’s approval rating hovered near an all-time low at 41% last week, according to Gallup Korea, compared with 84% immediately after his election in May 2017.

Back then, Moon was riding high on a successful people-power campaign to oust, prosecute and imprison Park, the conservative bloc’s standard-bearer and the daughter of a former dictator. At his inauguration, Moon pledged to “become the president for everyone.”

Moon’s decision to appoint one of his former secretaries to the justice minister’s post despite the investigations drew comparisons to Park’s cronyism. Cho has denied wrongdoing in a range of issues involving him and his wife, including their children’s university applications and an investment in a private equity fund.

The scandal caused the opposition bloc’s regular marches through Seoul to swell into the tens of thousands, while Liberty Korea Party chief Hwang Kyo-ahn shaved his head in protest outside Moon’s office. The demonstrations spread to universities, where students accused the president of tolerating the sort of favoritism he had vowed to stop.

The controversy overshadowed Moon’s stated reason for appointing Cho: Making prosecutions fairer by expanding ministerial oversight of investigations. Cho urged Moon to continue the effort in a statement Monday, saying he decided to “no longer put pressure on the president and the government with my family issues.”

The opposition LKP -- the successor of Park’s Saenuri Party -- has gained ground amid the scandal. A Realmeter poll released earlier Monday showed the LKP with about 34% of support, less than one percentage point behind the ruling party.

“Moon’s biggest loss in this situation were the people in the middle -- he read the people wrong,” said Choi Chang-ryul, a politics professor at Yongin University. “It may be hard for Moon to see his approval ratings bounce back up before the general elections next year.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Jihye Lee in Seoul at jlee2352@bloomberg.net;Kanga Kong in Seoul at kkong50@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, Jon Herskovitz

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.