Why Some Surprising Countries Are Setting Net-Zero Goals

Why Some Surprising Countries Are Setting Net-Zero Goals

(Bloomberg) --

Russia, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates, three of the world’s most fossil-fuel reliant countries, signaled last week that they could be net-zero within decades.

The news provoked two polar reactions: Delight that even the most recalcitrant nations acknowledged the threat of global warming, or declarations that “net-zero” had lost all credibility if any petrostate could simply declare a target without any accountability.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle. Let’s take the countries one at a time.

President Vladimir Putin has long dismissed the link between human activities and climate change. And, yet, as Bloomberg News reported earlier this month, a number of factors may have gotten him to change his mind to the point of considering a 2060 net-zero goal.

First, the European Union seems serious about levying a carbon-border tariff that will likely force Russian companies to pay for excess emissions in key industries. Oil and gas sales account for 35% of the country’s budget and coal remains a key source of employment. Second, some of his closest aides, such as the head of state-owned Sberbank, have warned him about how much damage climate change could cause the country, including to his hometown St Petersburg.

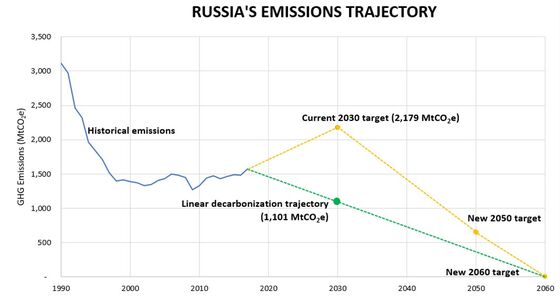

A 2060 net-zero goal will require the government to restructure its economy. The country’s most recent submission to the United Nations under the Paris Agreement would have seen it increase its emissions by 30% by the end of the decade, relative to 1990 levels. Getting to net-zero in the next forty years would require a 65% reduction instead, according to the World Resources Institute.

Turkey’s climate reformation has echoes of Russia’s. Also led by a strongman, Turkey last week became the last Group of 20 country to ratify the Paris accord. It had been holding out for approval to be classified as a developing country, which would mean a lower threshold for cutting emissions and access to international climate financing. While it may not get reclassified, the ratification could help Turkey avoid some of the impact of EU’s planned carbon-border tariffs.

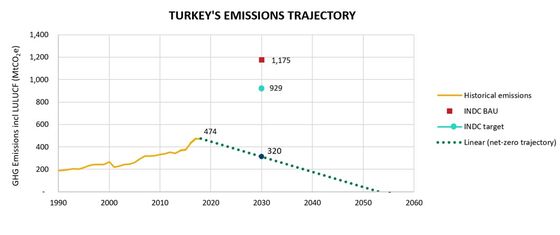

If Turkey is serious about reaching net-zero emissions by 2053, the target its cabinet has set, it will need to take drastic action. Instead of doubling emissions by 2030, which was its initial commitment based on WRI’s analysis, it will have to decrease emissions 30% by 2030 instead.

The UAE, meanwhile, has been trying to diversify its economy for decades with little success. At 30% of gross domestic production, oil and gas still forms a large chunk of its economy, though it’s still lower than Saudi Arabia’s share of 50%. One reason for the country’s 2050 net-zero goal, which was announced last week, could be its desire to be considered a climate leader in the region.

It could also become a supplier of lower-carbon fossil fuels, a product that many expect to be in high demand as companies try to decarbonize their supply chains. The UN’s carbon accounting rules mean countries only need to worry about emissions within their geographic territories, which would allow UAE to keep exporting oil and gas even as it technically meets the net-zero goal.

None of the countries have yet presented credible short-term targets or explained how they plan to move their economies away from fossil fuels. Yet, their new rhetoric is unlikely to be all greenwashing. “The intended audience is as much internal as external: it gives direction to local industry about the need to evolve and offer products that the world wants,” said Nikos Tsafos, an energy and geopolitics expert at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. “It is an effort to stay on the map as the world's map changes.”

So it’s in their interests — either to avoid climate impacts and carbon taxes or for geopolitical posturing — to do more to reduce emissions. But will these carbon states deliver on these pledges? “A vague promise buys you some time to keep with business-as-usual but not much,” said Tsafos.

The idea of net-zero was born from decades of scientific research that shows there’s no way to stabilize global temperatures without ensuring that sources and sinks of carbon dioxide are brought into balance. But perhaps a greater benefit is its simplicity. Every large emitter — national or corporate — needs to hit net-zero as soon as possible. Making a public declaration is only the first, and easiest, step.

Akshat Rathi writes the Net Zero newsletter, which examines the world’s race to cut emissions through the lens of business, science, and technology. You can email him with feedback.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.