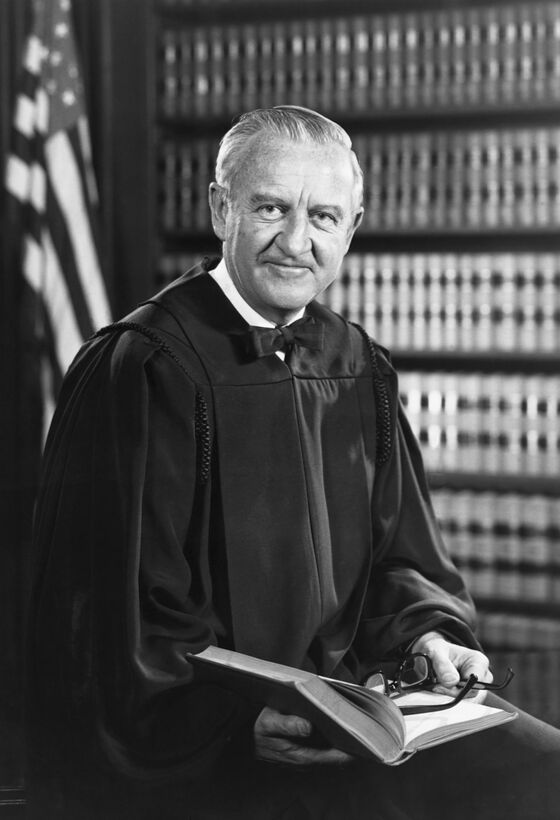

Retired Supreme Court Justice Stevens, Liberal Voice, Dies at 99

Retired Supreme Court Justice Stevens, Liberal Voice, Dies at 99

(Bloomberg) -- John Paul Stevens, who was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by a Republican president only to become a leading liberal voice on presidential powers, the death penalty and individual rights, has died. He was 99.

The retired justice died Tuesday at a hospital in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, of complications following a stroke he suffered on Monday, the Supreme Court said in a statement.

“He brought to our bench an inimitable blend of kindness, humility, wisdom, and independence,” Chief Justice John Roberts said in a statement. “His unrelenting commitment to justice has left us a better nation.”

Stevens was selected to join the federal bench in 1970 by Richard Nixon and nominated to the Supreme Court in 1975 by Gerald Ford. He retired in June 2010 at age 90 as the second-oldest justice in U.S. history.

He evolved from a somewhat lonely maverick, fond of writing separate opinions to make fine legal distinctions, into a coalition-builder whose handiwork included the 2004 opinion that said U.S. courts had authority over suspected terrorists held at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba.

Stevens also spoke for his wing of the court in high-profile dissents, as when the justices in 2010 struck down decades-old restrictions on campaign spending by corporations.

He dissented from the court’s 5-4 decision stopping the Florida ballot recounts that might have led to Democrat Al Gore’s election over Republican George W. Bush in 2000. Stevens accused the majority of ordering “the disenfranchisement of an unknown number of voters whose ballots reveal their intent.”

He remained engaged in public debate, sometimes controversially, even in his final years. Last year, he called for the repeal of the Constitution’s Second Amendment, which protects gun rights, and said the Senate shouldn’t have confirmed Brett Kavanaugh to the court after his performance at his confirmation hearing. Stevens had been in the process of writing a new memoir.

A statement by the White House released late Tuesday said his “work over the course of nearly 35 years on the Supreme Court will continue to shape the legal framework of our nation for years to come. His passion for the law and for our country will not soon be forgotten.”

Court’s Shift

Stevens took issue with the popular view that he became more liberal during his long career. To him, the court moved to the right.

“To the extent I look back at earlier situations, I really don’t think I’ve changed all that much,” he told the New York Times in 2010.

One major exception was capital punishment. In 1976, his second year on the court, he voted to re-establish the death penalty, ending a four-year moratorium. His views on the matter changed over the subsequent three decades.

He wrote the 6-3 decision in 2002 that prohibited executions of intellectually disabled killers, saying the practice was cruel and unusual punishment banned by the Constitution. In 2005, Stevens joined a 5-4 decision outlawing executions of murderers who were under 18 at the time of the crime, and he later told the American Bar Association that science-based exonerations of some death-row inmates had proven “serious flaws in our administration of criminal justice.”

Near-Record Tenure

In 2008, he announced that he believed the death penalty was unconstitutional, citing the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. In 2010, five months after leaving the court, he wrote an article for the New York Review of Books detailing his view that the court had failed to stand behind safeguards that would make the death penalty fair and appropriate in limited cases.

His tenure of 34 years, six months and 10 days as a justice was the third-longest in history, one day behind that of 19th-century justice Stephen Field and about two years behind that of William O. Douglas, whom Stevens succeeded in 1975. He survived prostate cancer and open-heart surgery during his time on the court.

“If I have overstayed my welcome, it is because this is such a unique and wonderful job,” Stevens wrote in a letter to his colleagues on his final day.

President Barack Obama named Elena Kagan, his solicitor general, to succeed Stevens.

Friendly, Traditional

Cordial and bow-tied, Stevens never built the sort of national fame accorded to justices appointed after him. His old-fashioned habits inside the court included writing his own first drafts of opinions, rather than assigning them to clerks.

He was an avid bridge and tennis player who once hit a hole-in-one while playing golf. He flew his own airplane for a time and in 2005 threw out the ceremonial first pitch at a Chicago Cubs baseball game. His affection for the Cubs traced to his childhood in Chicago, where he witnessed, from the stands at Wrigley Field, Babe Ruth’s famous called home run during the 1932 World Series.

Stevens was born April 20, 1920, in Chicago, the youngest of four boys of Ernest Stevens and the former Elizabeth Street. His father built and owned the Stevens Hotel, later to become the Chicago Hilton, and the four boys modeled for bronze sculptures in the Grand Stair Hall, according to a Washington Post report in 2005.

The family lived in Hyde Park, near the University of Chicago, and the boys attended the university’s Laboratory School.

Family Tragedy

Ernest Stevens, along with his brother, Raymond, and their father, James, who had made the family’s fortune as founder of the Illinois Life Insurance Co., were indicted in 1933 on charges that they diverted money from the insurance company to keep the hotel afloat during the Great Depression. Raymond committed suicide, and James suffered a stroke, so Ernest, father of the future justice, faced trial alone and was found guilty of embezzling $1.3 million.

The Illinois Supreme Court overturned the conviction in 1934. John Paul Stevens said the experience helped shape his view “that the criminal justice system can misfire sometimes.”

Stevens attended college at the University of Chicago, graduating in 1941. A year later he married Elizabeth Sheeren, with whom he had a son and three daughters.

He enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II and worked on a code-breaking team, earning a Bronze Star for meritorious service.

Antitrust Specialist

He graduated from Northwestern University’s law school and clerked on the Supreme Court for Justice Wiley B. Rutledge before going into private practice, specializing in antitrust cases.

In 1951, he was Republican counsel for a congressional committee examining the nation’s antitrust laws. He also served on an antitrust panel that advised the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower.

Stevens served as a federal appellate judge in Chicago from 1970 to 1975 before being unanimously confirmed by the Senate for a seat on the nation’s highest court.

From his early days on the bench, he escaped easy ideological labels, often focusing on the practical consequences of particular cases.

He wrote the court’s 1978 opinion letting the Federal Communications Commission punish broadcasters for airing offensive language when young children are likely to be listening. He said a New York radio station “could have enlarged a child’s vocabulary in an instant” when it aired comedian George Carlin’s monologue about seven “filthy words” excluded from polite conversation.

Gay Rights

In 1986, when the court said state and local governments could ban homosexual acts, Stevens said in dissent that gays share the same rights to sexual privacy as heterosexuals. The court overturned that ruling in 2003, with Stevens in the 6-3 majority.

When the court ruled in 1989 that the Constitution’s free-speech clause protects people who burn the U.S. flag, Stevens again dissented, saying that “sanctioning the public desecration of the flag will tarnish its value.”

As the court during the late 1980s and 1990s reduced criminal suspects’ rights and lowered the barrier between government and religion, Stevens at times found himself on the short end of 8-1 rulings.

Dissenting Voice

He was the only dissenter from a 1996 decision that said police officers don’t have to tell people stopped for traffic offenses that they are free to leave without submitting to a search. He was in the minority again in 1998 when the court, voting 8-1, denied defendants the right to use a lie-detector test in their defense.

In 2004, he wrote a majority opinion holding that a California atheist lacked the right to challenge whether public-school teachers may lead recitations of the Pledge of Allegiance with the phrase “under God.”

The following year, Stevens wrote for the majority in the 5-4 ruling that gave local governments broad power to take over private property to make way for shopping malls, office parks and sports stadiums.

Stevens had four children -- daughters Kathryn, Elizabeth and Susan, and son John, who died of cancer in 1996 -- with his first wife. That marriage ended in divorce in 1979. A year later he married his second wife, Maryan Mulholland Simon, who had five children. She died in August 2015.

To contact the reporter on this story: Greg Stohr in Washington at gstohr@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Joe Sobczyk at jsobczyk@bloomberg.net, John Harney, Laurie Asséo

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.