The Rage Against Pedro Sanchez Is Tearing Spain Apart

The Rage Against Pedro Sanchez Is Tearing Spain Apart

(Bloomberg) -- Spaniards are getting really worked up about Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez. At one point last month, the defaced image of the photogenic Socialist was plastered across a giant red banner hung in downtown Madrid.

The trigger has been his widely-criticized handling of the coronavirus pandemic that has seen Spain suffer among the highest death tolls in Europe. But as the worst of the trauma starts to fade, the vitriol has only gotten worse. The opposition is stirring legitimate criticism with paranoia, crackpot conspiracy theories and ancient resentments into a toxic brew.

The country is emerging from its three-month lockdown now. But the backlash in the capital is growing — one penthouse has been raining down anti-government leaflets on protesters gathered in the street below.

The anger is palpable on social media feeds and in parliament, where 48-year-old Sanchez scraped together enough votes to extend his state-of-emergency powers this week with the furious opposition dredging up his coalition partner’s ties to Venezuela to paint the prime minister as a wannabe authoritarian.

“We’re fighting for Spain,” said Jose Luis Marin as he led a few dozen pan-banging marchers through one of the capital’s swankiest neighborhoods. He was brandishing a 3-meter long Spanish flag with the word “Libertad” — freedom — scrawled across it.

In truth, tensions were always bubbling under the surface and the virus has simply turned up the temperature in Spain’s long-running culture wars. Broad swathes of the population questioned Sanchez’s legitimacy from the moment he took office.

“I’m fascinated by the absolute hatred for Pedro Sanchez in certain parts of the right,” Roger Senserrich, a political scientist based in New Haven, Connecticut, observed on Twitter. “He’s a pretty normal politician, mediocre in almost everything, just as ambitious as any other leader of a national party and probably just as (in)competent. But my god, the hatred. It’s brutal.”

A spokesman for the prime minister declined to comment.

Spain is a young democracy that emerged from a military dictatorship in late 1970s to become one of Europe’s most thriving and socially liberal economies — and yet its politics remain fiercely partisan with sharp ideological fault lines reminiscent of the U.S. under Donald Trump or Boris Johnson’s Brexit Britain.

Sanchez is just as polarizing. That makes it almost impossible to imagine how its politicians will find common cause as it seeks a path out of a devastating recession.

“The right always tends to be very personal in its attacks,” said Ignacio Urquizu, a sociologist and former Socialist lawmaker. “It focuses on the leader.”

The images from the U.S. over the past week show how quickly order can break down when you put together longstanding divisions, acute economic hardship and a burning sense of injustice. To be sure, Spain has seen nothing like the Black Lives Matter protests as yet, but it has some of the same ingredients. And a few of its own.

For many of the conservative voters who make up about a third of the Spanish electorate, Sanchez’s original sin was to forge an alliance with the radical left group Podemos and the separatists of Catalonia and the Basque Country.

Those groups came together in a 2018 no-confidence vote to oust the center-right People’s Party, which had been limping along since losing its majority three years earlier.

Conservatives objected, with some justification, that Sanchez was lining up with lawmakers that wanted to undermine Spain’s constitutional order or, in the case of the Catalans, had actually tried to break up the country. They say his willingness to cut deals with those groups now to keep his minority coalition in power betrays his lack of scruples.

“They’ve watched too many TV shows like Game of Thrones and House of Cards,” says PP official Javier Fernandez-Lasquetty, economy chief for the Madrid region. “That’s not how politics works in real life.”

Parliamentary rules require any no-confidence motion to propose an alternative premier, so it’s highly unlikely the PP can force Sanchez out.

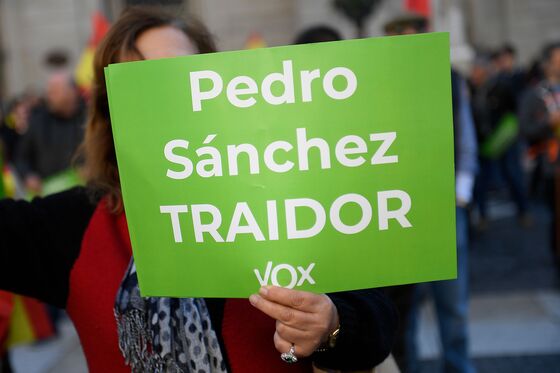

All the same, at the start of the pandemic there was a moment of national unity. When Sanchez declared the state of emergency in March, not even the far-right group Vox voted against him.

It didn’t last.

Spain has been in the grip of a slow-motion constitutional crisis since 2015. Four general elections in that period have failed to produce even one stable executive, stirring up memories and grudges from the Civil War almost a century ago. The virus eventually made all that worse.

With the PP controling Madrid, which has been at the epicenter of the outbreak, the tensions have been focused in the capital.

When Sanchez started to lift restrictions in the rest of the country, Madrid and Barcelona were kept under lockdown and resentments started to build. Regional leaders said that the government’s criteria were neither transparent nor objective.

“It was a pure show of force,” Lasquetty said in an interview. “Madrid felt mistreated. That explains what happened in May.”

As relations unraveled, Madrid President Isabel Diaz Ayuso turned up an hour and a half late for one appointment with Sanchez and walked out of another. When the state of emergency expires on June 21, she will have much more control over the next phase of the capital’s reopening.

Sanchez is losing his special powers at a moment when he’s struggling for control on various fronts.

On top of the backlash on the streets, the prime minister has found himself embroiled in a fight with the Civil Guard, the country’s biggest police force. One of the force’s most senior officers was fired after it emerged that his officers had prepared a report critical of the government’s handling of the coronavirus, prompting cries of interference.

Meanwhile protesters have been openly defying the terms of the lockdown. Those actions that have led to tens of thousands of fines in the rest of the country. But police in Madrid have on the whole turned a blind eye, perhaps wary of inflaming the situation.

“If the economic situation gets worse, there is a chance that it may all expand beyond Madrid,” says Urquizu.

The opposition is doing all it can to fan the flames and Pablo Iglesias, deputy prime minister and Podemos’s leader, is a lightning rod. The scruffy former academic, nicknamed derisively “the Ponytail” in reference to his trademark long hair, spent time in Caracas advising the Hugo Chavez government before setting up his party.

When the 41-year-old first took his seat in parliament, he provocatively planted a kiss full on the mouth of a male colleague right in front of the conservative economy chief Luis de Guindos, to roars of approval from his party.

In a heated debate in parliament last week, the PP’s main spokeswoman Cayetana Alvarez de Toledo dredged up Iglesias’s links to the left-wing government that has ravaged Venezuela for a generation. Alvarez de Toledo, an Oxford-educated aristocrat with an exotic-sounding Argentinian accent in Spanish, said the government is seeking to undermine independent state-institutions by appointing cronies and labeled Iglesias the son of a terrorist — a reference to his father’s activism during the dictatorship.

“You have a plan, it’s true, it’s a plan against democracy,” Alvarez de Toledo, 45, said. “You want to create an authoritarian left-wing regime.”

Those arguments mutate as they filter through the protests on the streets of the capital where angry, confused people are trying to process the events of the past few months.

“They have done it badly on purpose,” said Carmen Corbera, at one protest, a Spanish flag stitched onto the side of her face mask and another pinned to her shoulders like a cape. “It was convenient for them to establish the communist regime that Pedro and Pablo want for Spain.”

To be clear, there is zero evidence either that the pandemic was deliberately mishandled, or that the government is plotting to set up a communist regime.

A Chavista takeover is not the real threat for Spain.

The danger is that the country’s entrenched political factions are increasingly inhabiting parallel realities and leaving the country unable to face its mounting challenges. The lines at food banks are growing and in the weeks to come more and more people are likely to be sitting at home, out of work, and looking for someone to blame.

Spain needs a prime minister to revive the battered economy, to stabilize the public finances and then get to work on the difficult process of fixing the democratic system.

But like millions of his country’s people, Sanchez is just trying to get to the end of the month.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.