Opaque World of American Meat Trading Leaves Farmers Squeezed

Opaque World of American Meat Trading Leaves Farmers Squeezed

(Bloomberg) -- It’s almost impossible to hedge a hog in a pandemic.

As coronavirus outbreaks sparked a U.S. meat crisis with shuttered plants and supply shortages, margins for meatpacking companies soared more than seven-fold in a little more than a month. But farmers got squeezed -- prices for their animals stayed low, and many were left with a backlog of animals as slaughterhouses closed.

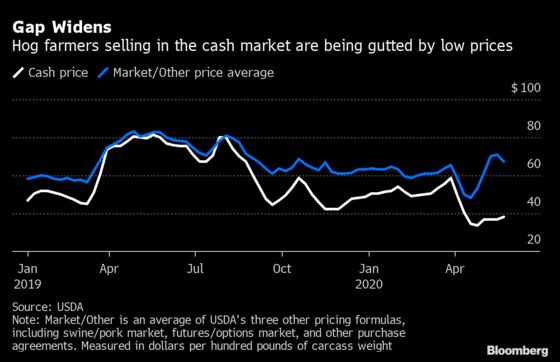

Some farmers were getting paid less than half of what others got, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture price quotes.

Analysts, farmers and other experts are pointing to an obscure corner of the hog industry -- deals that on some days make up less than 2% of the market -- as part of the underlying problem.

The so-called negotiated trades are an old-school way of trading pigs, allowing for quick cash deals on animals for delivery in 14 days or fewer. They’re little used because most contracts now are done for the longer term, but the USDA and others collect data from the trades to underpin prices across the market. The biggest problem with the trades, farmers say, is they’re not tied into the price of meat.

America’s opaque livestock pricing mechanisms are coming under fresh scrutiny after meatpacker profits surged amid the plant shutdowns. The U.S. Justice Department is investigating companies for possible antitrust violations. While that probe started before the coronavirus outbreak, the pandemic has thrust this little crevice of the commodity world into the public spotlight. The USDA is also separately investigating the rise in margins.

How do pigs get priced in America? It’s a complex system that uses varying methods, sometimes only accounting for the cost of the animal, and sometimes also factoring in the pork price. The USDA publishes lists of cash trades, but spreads can be huge.

The weird and complicated pricing methods became even more tricky to navigate as processing plants shuttered. Packers -- the folks who do the slaughtering and turn pigs into chops and bacon -- were buying less livestock, but because meat demand was so high, their margins skyrocketed. Farmers, on the other hand, were forced to euthanize pigs with fewer plants open where animals could be processed.

No segment was hit harder than the negotiated trades in the cash market. With more than 30% of capacity off line, packers prioritized slaughtering the animals they already owned and hogs sold by farmers with longer-term contracts. Left out were farmers still selling animals in the open market.

“The negotiated market has fallen through the floor,” Dermot Hayes, agriculture economist at Iowa State University, said by telephone.

That drop had an outsized impact. Even though the trades are a tiny part of the market, they’re used to calculate contracts all across the industry. They also help give direction to futures traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the global benchmark.

“It’s a big problem and it’s been there for a long time. Now, we have a mismatch with supply and demand,” said Steve Meyer, an economist at consultancy Kerns & Associates. He estimates farmers are dealing with a backlog of 2.4 million hogs, while 400,000 have been euthanized.

No Tie to Meat

This week, as packing plants were still struggling to operate at full capacity, farmers trading in the negotiated spot market fetched an average of $38.38 per 100 pounds, according to USDA data. Meanwhile, hogs traded on contracts based on formulas that can be comprised of animal or meat prices averaged $64.26.

Part of the problem in the industry is that the negotiated trades don’t take into account the price of meat. So even when wholesale pork is surging, animal prices can stay low, giving mixed signals to farmers that are trying to hedge.

Farmers have been pushing for contracts tied to pork prices, ensuring that they get a share of the packers’ profits. But those coveted contracts are hard to come by.

The pork price, known in the industry as the cutout, is up 75% since April 9. July hog futures are little changed over that period. The CME Lean Hog Index, a gauge of the cash market, is up about 19%.

“The more spread out that cash and the cutout get, the more difficult it is to make hedging decisions,” Tim Hughes, who leads hog-margin management at Commodity & Ingredient Hedging LLC in Chicago, said by telephone.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.