One Brexit, Two Systems: U.K. Manufacturers Brace for More Costs

One Brexit, Two Systems: U.K. Manufacturers Brace for More Costs

(Bloomberg) -- Whenever Mike Ashmead builds a new motorcycle model, he pays about 120,000 pounds ($154,000) for a certificate proving it complies with European Union standards.

Once Britain leaves the bloc’s regulatory orbit in 2021, the founder of Herald Motor Co. fears he will have to pay the charge twice.

“If you have a different one for the U.K., that’s another 120,000 pounds,” said Ashmead. That could be 10% of parent firm Encocam Ltd.’s annual profit. “It’s quite a significant amount because it comes off the bottom line.”

Ashmead’s worry is shared by many British manufacturers: after spending three decades aligning with the EU’s rules and processes, they now face cost and upheaval as Boris Johnson’s government breaks with the bloc. While the government has touted the freedom to diverge from EU rules as one of the big benefits of leaving, businesses say they are unsure of the benefit to them.

For companies wanting to sell their products in both Britain and the EU, the risk is they will have to get product approvals in two separate regulatory systems from 2021 because the U.K. has refused to automatically adopt the bloc’s rules after Brexit. Johnson and his team have ruled out such so-called regulatory alignment, saying the very point of Brexit was to take back control of its laws.

Vital Market

“It seems ridiculous to me,” said David Smith, managing director of Specac Ltd., a Kent-based maker of laboratory equipment. “We’ll have given ourselves a whole new extra level of burden to do the same thing we were doing before.”

His firm, which employs about 80 people and generates annual sales of 13 million pounds, exports 20% of its products to the EU. He said he he would stomach any extra compliance fees -- but expects them to put other firms off selling to the bloc.

“We’ll do it because we have to, because it’s a vital market for us,” he said.

Other companies would consider abandoning the U.K. market if their regulatory burden increased due to Brexit. EMS Physio, an Oxfordshire-based manufacturer of medical appliances which makes 80% of its sales to the rest of the world, said it would weigh such an option: keeping manufacturing in the U.K., but not selling its products there.

“Regulatory alignment is crucial,” said James Greenham, the company’s managing director. “And more importantly, what regulations will be implemented in the U.K., and how we must adapt and pay for these new regulations.”

The U.K. aims to strike a deal on mutual recognition of regulations and testing in the trade talks with the EU, and the issue features in both sides’ negotiating mandates published this month. Britain’s hope is that, in areas where their rules and processes remain similar, the EU will acknowledge them as being equivalent, something that would at least reduce the additional red tape for business.

‘Well Sorry’

“It should be something that is achievable, but it’s not the same as what we have now,” said Namali Mackay, an independent trade adviser and former trade negotiator for Australia. She said companies would still face new transactional costs in the form of additional paperwork, but the burden would be reduced.

“The only reason it won’t come about is if it’s used as a negotiating chip,” Mackay said. “For example, the EU may say: ‘Well sorry, if you’re not willing to budge on fish, we’re not willing to budge on mutual recognition.”’

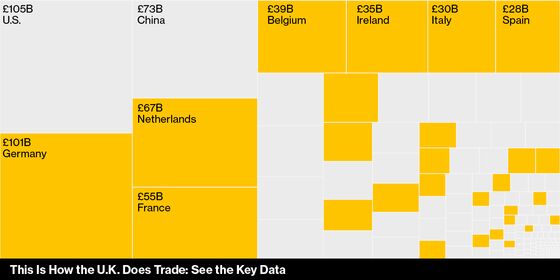

Even in the most benign post-Brexit trade deal with the EU, the government expects 200 million extra customs forms a year will be needed to keep U.K.-EU trade humming. That’s because about 54% of U.K. goods imports are from the EU, the destination for half the country’s exports. At 32.50 pounds apiece, declaration forms would cost exporters and importers about 6.5 billion pounds more a year.

In the areas where Britain wants to depart from EU rules, the U.K. government sees opportunities. David Frost, Britain’s chief Brexit negotiator, said in a speech this month that any short-term harm from new trade friction caused by leaving the bloc’s single market and customs union would be outweighed by long-run benefits from regulatory divergence.

But, for now, business is focused on the immediate impact to EU trade.

“We need to get to the end of this year and still be able to export,” said Christopher Greenough, chief commercial officer at SDE Technology, a Shrewsbury-based maker of metal parts used in automotive production which makes 10% of its sales to Germany. “It would be very silly to change any regulations that mean we can’t then send goods to the EU.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Joe Mayes in London at jmayes9@bloomberg.net;Alex Morales in London at amorales2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net, Thomas Pfeiffer

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.