NYC Schools Quell the Virus Only to Face Education Challenges

NYC Schools Quell the Virus Only to Face Education Challenges

(Bloomberg) -- New York City has successfully kept Covid-19 from invading its school buildings, offering hope to a nation hesitant to return children to classrooms. Now it must maintain those low levels as it tries to lure more students.

America’s largest public-school system begins its only opt-in period Monday for remote-school students willing to give a blended program a shot. If they don’t switch by Nov. 15, they will be remote for the rest of the school year -- an option that district officials say results in students learning less than with in-class instruction.

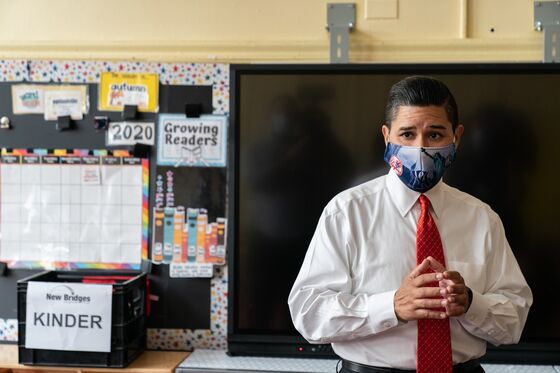

“We’re lower than we anticipated in terms of in-person learners, and know that families initially had hesitations,” Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza said during an Oct. 26 news briefing. “There is no replacement for in-person learning, and it’s safe to do so.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed a blended program in late August that called for socially distanced classrooms, mandatory masks, a contract tracing program and a requirement that the citywide transmission rate stays below 3%.

He has said in-person school is “crucial” for students and their families. For months, he had predicted 70% of the system’s 1.1 million students would participate in the blended program. But parents withdrew their kids in droves last month. As of last week, about 25% were in school part-time.

The city has an overall attendance rate of about 85%, down from 92% at the end of the 2018-19 school year. Students with less than 90% attendance “are more likely to have lower test scores and not graduate from high school,” according to the district’s website.

Absent Students

Art Zander, who teaches sixth-grade math and science at Elizabeth Blackwell Middle School in south Queens, said some new students haven’t shown up yet for in-class learning. “Sometimes they don’t have a device or internet connectivity, and it may take some effort finding out where these kids are. We have teachers telling us: ‘I’m supposed to have 30 kids in class, and six haven’t reported.’ ”

For all the worries, the system’s school buildings have proved to be havens of public-health safety, almost devoid of infection. After about 63,000 tests in 1,200 schools, just 69 were positive for Covid-19, the mayor said Friday. He described the achievement as “astounding,” saying it should motivate parents to send their kids back.

“What it says is our schools are extraordinarily safe,” de Blasio said. “We’re not seeing movement in the wrong direction of schools. We’re seeing incredible stability in the schools, very, very low level of test positivity. And that is a blessing.”

Among school districts in other major U.S. cities, Los Angeles and Nevada’s Clark County remain closed, while Chicago plans to open buildings for just pre-kindergarten and special education later in the second quarter, which ends in early February. Miami schools reopened in October, and have since reported 343 Covid cases.

While New York City schools may be safe, questions remain about whether the kids in class are getting a better education than the ones at home. The school year has been plagued by staff shortages, disorganization, low attendance, spotty internet connections and dysfunctional city-provided mobile learning devices, according to parents, teachers and students.

No Choice

Kanika Ingram, a parent of three and an essential worker for Verizon, says she must stick with the blended program even though she’s frustrated with it. She finds her fifth-grade son’s experience acceptable because he has the same teachers in person and online.

But that’s rare. Her daughter’s second-grade class gets five days of in-school every two weeks, while on the other days she gets one hour online with the gym teacher, who gives an assignment from a workbook. Her son who just started high school has no English or social studies teacher on remote days, she said.

“It’s terrible, it’s disgraceful,” said Ingram, who is PTA president at her daughter’s PS 21 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. “How could the Department of Education not have the wherewithal to know if you’re going to have part-time in-class and remote instruction, and full-time remote, you’re going to need more teachers?”

One Time

School officials had promised parents they would have several opt-in chances during the school year. They decided to offer it just once so that school principals wouldn’t be forced to keep changing teaching assignments. “We think that this is better for the sake of stability for all students, for families and educators,” Carranza said last week.

Even after the opt-in period, the split schedules will produce daunting demands on personnel, teachers say.

Evan O’Connell, who teaches high school history and government at Metropolitan Expeditionary Learning School in Queens, says his in-school classes are so sparsely attended that he’s been teaching all his substantive course work online to more than 30 students at a time. He uses in-school time to give a handful of students help with college application essays or to let them catch up on homework.

“Teachers are being torn in a million different directions, going in on some days, practicing remotely other days,” he said. Online classes present unique challenges, he said, “because the tech issues are very real for some kids, and it’s so hard to measure engagement when you can’t read facial expressions and body language.”

While remote learning offers the benefit of reducing the risk of spreading the virus, some studies have found it can disadvantage students. An April report by the NWEA, an Oregon-based nonprofit research organization, found that students in remote class achieved only 70% of the learning gains in reading and 50% in math they would have made in a typical school year.

On Edge

O’Connell was forced into all-remote mode when his school was closed last month after Covid-19 was detected in his building. He and his colleagues learned about it the night before the shutdown, causing them to hurry to notify parents. It contributed to a sense that anything could change at any moment, he said.

Greg Monte, who teaches social studies at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School in Brooklyn, said students were gathered into large rooms where they spread out to receive lessons streamed into their tablets and laptops from a teacher in a nearby empty classroom. That was until the building shut down early in October and went all-remote because it was in a state-designated coronavirus hot zone.

“I was in the building, but my kids were at home or in the cafeteria,” he said. “One good thing is it minimized contagion.”

In-person learning isn’t going to happen for Gabe Lipschutz, a senior at the Bronx High School of Science, who says teacher staffing issues forced the school to cut electives, “so there was no purpose commuting long distances on the subway to come in.” About 90% of his fellow students chose to learn remotely, he said.

Likewise, Rasheedah Harris said in-class instruction isn’t worth it for her 10-year-old daughter, who attends fifth grade at home with a neighboring boy assigned to her same all-remote class. “Sure they miss their friends, the school building and their teachers. But the thought of sitting in class all day with a mask on, only to log on to laptops at their desk -- what’s the point? And why is it worth the risk?”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.