Repo Market Is Telling Washington That Deficits Still Do Matter

MMT Is All the Rage, But Repo Spike Shows Deficits Still Matter

(Bloomberg) --

These days, you’d be hard-pressed to find many people in Washington who are all that worried about the U.S. budget deficit. Republicans seem more interested in tax cuts, Democrats have ambitious spending plans for everything from health care to infrastructure, and Modern Monetary Theory, a manifesto for free-spending governments, is all the rage in progressive circles.

But on Wall Street, bond dealers provided a small, but pointed reminder that, just maybe, debt and deficits do matter after all.

It came in the form of a sudden spike in interest rates for repurchase agreements, or repos, a normally obscure part of finance that keeps the global capital markets spinning. Plenty of factors helped cause liquidity to dry up, but one that’s getting more attention is concern that dealers are starting to choke on Treasuries as the U.S. government goes deeper into the red.

The argument goes like this: Primary dealers, which are obligated to bid at U.S. debt auctions, have absorbed more and more Treasuries to finance the Trump administration’s tax cuts as investor demand has waned. Typically, they rely on repos to fund those purchases by putting up the debt as collateral.

The problem is that with the financial system already inundated by over $16 trillion of Treasuries, banks constrained by crisis-era rules have fewer incentives to participate in repo. Simply put, there was too much new debt flooding the financial system and not enough money, causing lenders to jack up repo rates. The Federal Reserve has moved to inject much-needed cash on a temporary basis, but if left unchecked, the flood of supply in coming months and years could ultimately result in higher borrowing costs for the U.S.

“There’s no down time on the supply front,” said Jim Vogel, a strategist at FTN Financial who’s been following debt markets for over three decades.

The Treasury’s next slate of debt sales comes this week, with a combined $78 billion of 3-, 10- and 30-year auctions starting Tuesday. Yields on the benchmark 10-year note are currently at 1.52%.

Of course, supply wasn’t the only issue. The situation was compounded by corporate tax payments that also siphoned cash out of the banking system.

And to be fair, nobody is suggesting the U.S. faces any imminent problems financing itself. Everywhere you look, government borrowing costs in bond markets around the world are at historic lows. The dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, and with the global economy showing signs of weakness, investors are still likely turn to Treasuries for safe harbor.

Nevertheless, the mid-September repo upheaval is a clear sign there might actually be limits on just how much debt the U.S. can take before triggering more frequent disruptions. Deficits aren’t exactly new, but they do add up. Since the crisis, the market for Treasury debt has roughly tripled in size.

And the fiscal balance has only gotten worse under President Donald Trump. The deficit surpassed $1 trillion in the first 11 months of the fiscal year, which just ended last month. And the Congressional Budget Office forecasts the shortfall this fiscal year will exceed $1 trillion. That all means the Treasury will need to keep increasing its debt auctions to fund the budget shortfalls.

In the coming decade, debt as a percentage of the gross domestic product will reach 100%, CBO estimates show. That would be greater than any time since just after World War II. Before the financial crisis, debt-to-GDP was about 40%.

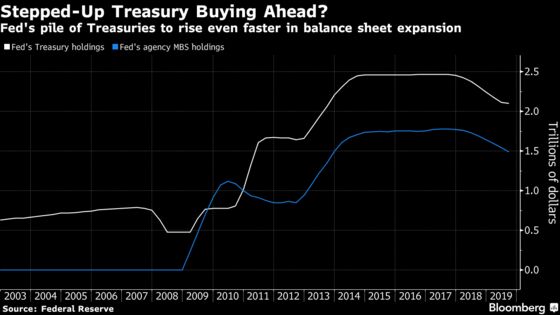

The growth was more than manageable in the years after the crisis because the Fed bought significant amounts of Treasuries (from dealers post-auction) with its quantitative easing, or QE. Some argue the Fed used QE to “monetize” the debt, which pumped trillions of dollars worth of cheap cash into the banking system and kept U.S. funding costs artificially low. Whatever the case, there’s little doubt the buying helped dealers clear their inventories.

That started to change in late 2017, when the Fed began to gradually unwind those purchases, reduce the size of its balance sheet and drain the excess cash held in bank reserves. The Fed now holds roughly $3.9 trillion in assets, down from $4.5 trillion in January 2015. More than half of the total is in Treasuries.

Without the Fed, which was arguably the biggest buyer of U.S. debt during the QE era, dealers have had to pick up the slack. In May, primary dealers’ outright positions in Treasuries reached an all-time high of almost $300 billion -- more than double what they were the previous year.

What’s more, post-crisis rules have led banks to prefer cash over Treasuries, which contributed to the liquidity issues in repo markets, according to Michael de Pass, head of Treasuries trading at Citadel Securities.

“The Fed has shrunk its balance sheet in a meaningful way, resulting in reduced reserves in the system,” he said. The cash squeeze has “been further exacerbated by increased issuance, resulting in high levels of Treasury collateral settling into the market.”

Dealers aren’t getting as much help from foreign investors to soak up all that additional supply. Big creditors like China and Japan have slowed their buying of Treasuries in recent years. Overall, the share of foreign official holdings has shrunk to just over 25% this year, from a high of about 40% in 2008.

That waning appetite been reflected in the amount of bids investors submit versus the actual amount sold, known as the bid-to-cover ratio.

According to an analysis by John Canavan, Oxford Economics’ lead analyst, the ratio for 3-, 10- and 30-year debt sold each month has fallen to 2.39. That’s down from 2.89 times in January 2018, just before the Treasury began boosting its sales, and far lower than a high of 3.48 times in December 2011.

So-called auction tails, which occur when yields on debt issued at auction exceed prevailing levels in the market at the time of sale, have become more common as well. In layman’s terms, it’s a sign investors need to be paid more to take on new debt. That’s been true especially for longer-maturity debt, like the 10-year note and the 30-year bond.

“The debt has become more difficult to digest as the rise in Treasury issuance is outpacing the rise in demand, and overall there’s been a decline in recent years in foreign demand,” Canavan said.

There’s little to suggest the U.S. will suddenly decide to embrace fiscal restraint, either under Trump or a Democratic administration.

So for many market watchers, the most likely near-term solution to the supply problem is for the Fed to start increasing its debt purchases in a systematic way once more. (Following the recent repo turmoil, the Fed has been providing repo financing on a temporary basis.)

Historically, pumping lots of cash into the system has come with the risk of spurring too much inflationary pressure. But after a decade of ultra-low inflation, that isn’t much of a concern today. The purchases would not only replenish bank reserves and help dealers off-load Treasury collateral, but it would also keep a lid on funding costs as the U.S. runs up the deficit.

Former Fed officials Joseph Gagnon and Brian Sack say the central bank should buy enough Treasuries to build up a buffer of extra reserves, with outright purchases totaling $250 billion over the next two quarters.

“More Fed buying may finally give some relief to the supply issues that the market so needs,” Vogel said.

When it comes to financing America’s deficit though, it’s not the Fed that Julius Baer’s Markus Allenspach is worried about.

“There’s going to be saturation by investors at some point,” said Allenspach, head of fixed-income research and a member of the firm’s investment committee. “Yes, there is a global search for yield, but we believe we may be past the peak of this hunt for safe assets.”

--With assistance from Alex Tanzi.

To contact the reporters on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net;Saleha Mohsin in Washington at smohsin2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Michael Tsang, Mark Tannenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.