Making Sense of the Narratives After the Glasgow Climate Talks

Making Sense of the Narratives After the Glasgow Climate Talks

(Bloomberg) --

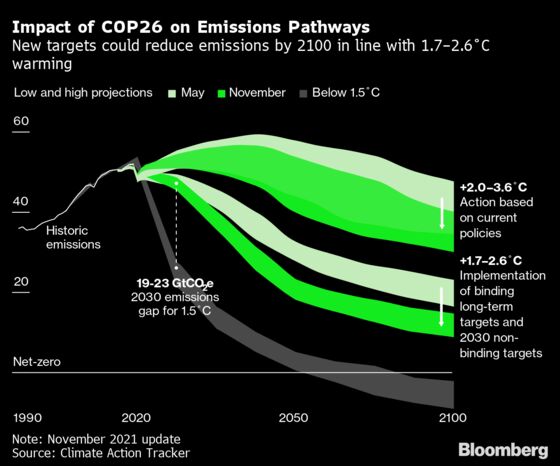

The COP26 climate talks in Glasgow ended with some progress, though not enough to ensure the world avoids catastrophic climate impacts. If countries meet their pledges, greenhouse emissions in 2030 will be slightly lower than previously projected. But a new report warns that the decline doesn’t mean we’re safe.

The in-depth study published on Monday, led by Ida Sognnaes at the Centre for International Climate Research (Cicero), showed that the temperature outcome based on countries’ climate pledges is full of uncertainties. Using data on goals set about a year ago, Sognnaes and her team found that the world could warm anywhere between 1.7°C and 3.8°C by 2100 compared with pre-industrial levels. Other analyses that used the most recent data from COP26 came to similar conclusions.

The vast range of possible futures is the reason to keep working harder to reduce emissions, said Glen Peters, research director at Cicero. The 1.7°C outcome “builds a narrative that maybe we’re very close, that we’ve done enough for now and that we don’t need to push so hard,” he said. But if you look at the 3.8°C outcome, then it’s clear “we’re a long way away and we need to lift our game.”

Both those narratives are playing out predictably.

In a sense, both sides are right. The lower end of Cicero's forecast would put the world very close to the most ambitious goal under the Paris Agreement to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C. That would result in many more extreme weather events than we face currently at 1.1°C of warming, but it’s likely to avoid triggering some irreversible changes such as the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet.

The upper end of the forecast would see the world blow past the less ambitious Paris goal of limiting warming to 2°C. A planet that’s nearly 4°C hotter would make vast parts of Earth uninhabitable, triggering mass migration of hundreds of millions of people and throwing the global economy into a tailspin.

It is perhaps the worst-case outcome that should make the headlines and guide policy makers and investors. Consider what happened in March 2020, when the world had reported only a few tens of thousands of cases of Covid-19. Then President Donald Trump cited a worst-case outcome of 2.2 million deaths in the U.S. alone as justification for putting his country in a lockdown. And it worked. Though the death toll is a devastating 770,000 today, it’s nonetheless far fewer than what it could have been.

To be sure, there’s definitely been progress. Before the Paris accord was signed, the Emissions Gap report from the United Nations projected possible warming to be between 3°C and 7°C by the end of the century.

Thanks to better climate modeling, cheaper green technologies and more willingness from governments to reduce emissions, the world is no longer on a path of utter destruction. And yet the worse-case outcome of apocalyptic 4°C warming still remains possible. That means there is little time to rest on the gains made at COP26.

Akshat Rathi writes the Net Zero newsletter, which examines the world’s race to cut emissions through the lens of business, science, and technology. You can email him with feedback.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.