Macron Flinches as Radical Islamists Hit France’s Pressure Points

Macron Flinches as Radical Islamists Hit France's Pressure Points

(Bloomberg) -- The killing of a high-school history teacher in a Paris suburb last week was a shocking, but painfully familiar experience for France.

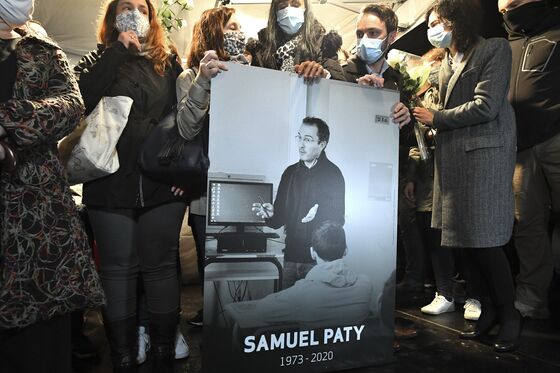

Thousands took to the streets to show their solidarity with 47-year-old Samuel Paty, beheaded for showing cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed to his students. They also recalled the Charlie Hebdo attack almost six years ago, when 12 people were gunned down at the magazine that first published the drawings.

“I am Charlie,” read the placards in January 2015. “I am a teacher,” they said this weekend. Even bigger crowds are expected to turn out on Wednesday when President Emmanuel Macron leads a memorial for the victim.

When the gruesome details of the murder broke on Friday night, Macron headed straight to the crime scene to issue a grim-faced defense of France’s free-speech principles. On Tuesday, he was back in a hot spot on the capital’s outskirts to take stock of efforts to stamp out radicalism, pointing to hundreds of prayer halls and secret schools shut down since he took office.

Fundamentalist violence is a defining issue for France that could cost Macron re-election in 2022.

“We know what we have to do,” he said. “Our fellow citizens are looking for action. The action is there and we’ll intensify it.”

Yet the tragedy in the middle-class neighborhood of Conflans-Sainte-Honorine hits on all the pressure points in France’s value-system that Macron has failed to eradicate three years after he defeated the anti-immigrant nationalist Marine Le Pen to claim power.

The tension between a republican constitution and a Muslim minority, like the struggle to integrate some migrants, is still there, bubbling under the surface, or exploding in sudden violence like in the case of Paty, often amplified by the social media echo chamber that challenges politicians everywhere.

“Secularism is key,” Education Minister Jean-Michel Blanquer said, a reference to the idea that French citizens should keep their religious beliefs out of public life. “It allows us to have differences, to believe or not to believe, and to respect each other.”

For many in France, a country that underwent a revolution to enshrine the separation of church and state, the question is whether that core principle can still hold in the classroom, in the work place and in government.

Paty had shared the cartoons in a class on freedom of speech. It was a lesson in civics that incurred the wrath of some Muslim parents. That hatred spilled online and morphed into a kind of call to arms. His killer in fact was an 18-year-old refugee from Chechnya with no links to the school. He was shot dead by police.

France’s relationship with its Muslim minority is complicated. The idea of secular citizenship is woven into the country’s identity — and religious iconography is therefore banned. In schools, where the culture wars play out, it’s a matter of principle that there are no crucifixes hanging on walls and girls aren’t allowed to wear veils.

That should, in theory, guarantee diversity and neutrality, but it’s not always the case.

Muslims face discrimination in the job market, and during the lockdown earlier this year young Arab and African men were disproportionately stopped by police. The government’s response to Islamist violence has left many feeling further stigmatized.

But there’s also the roll-call of attacks since the magazine shootings — the Kosher supermarket, the Bataclan concert hall, the sea front in Nice. Even last month, as the trial of the Charlie Hebdo killers began in Paris, a man armed with a meat cleaver wounded two people outside the magazine’s former offices.

“The trial was supposed to bring closure,” said Claude Dargent, a sociology professor at Paris 8 university. “People thought they would be able to put these events behind them.”

Paty’s murder shows how deep the problems run. Islamic extremism has been one of the key issues throughout Macron’s brief career in front-line politics.

His one-time mentor, former President Francois Hollande, was criticized for failing to keep people safe after the Charlie Hebdo attack. At the time, Le Pen offered a straightforward response to the challenge: a crackdown on immigration and a defense of traditional (white) French values and jobs.

The 2017 election came to hinge on Le Pen and the question of immigration. Macron, a self-professed liberal, offered France an alternative to the xenophobia of Le Pen’s National Front and voters backed him.

Now Le Pen is running neck and neck with Macron in polling for the first round in 2022 and the problems that fueled her rise to prominence are back. Macron himself has said it will take years to eradicate Islamic extremism in France.

The Yellow Vest protests against his supposedly elite, metropolitans ways showed the president struggles to connect with many white, working class voters, a problem the pandemic-fueled recession can only exacerbate.

On top of that, the Black Lives Matter protests of this summer revealed the well of resentment among minority groups over their treatment by the French police. Throughout his presidency, Macron appeared at times to be calculating just how liberal he could afford to be.

He has tried to keep to the center, but his most recent moves suggest he’s tuned into the threat from nationalists like Le Pen.

Less than three weeks ago, he broke off early from a European Union leaders’ summit to return to a place not far from the murder scene to set out his plans to regulate Islam in France and force radical Muslims to respect the values of the republic.

In July, he chose a hardliner as his interior minister. Gerald Darmanin was with Macron when he visited Paty’s school on Friday night and he has been omnipresent since, promising to flush out what he calls “the enemy within” and shutting down a mosque. “We must stop being naive,” Darmanin told a French radio station. “It’s better to wake up late than never.”

The experiment with a liberal approach may be drawing to a close.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.