Low Inflation Is Federal Reserve’s Maddening Unsolved Mystery

U.S. inflation is like a cold case that still baffles investigators.

(Bloomberg) -- It’s like a cold case that still baffles investigators. After years of rock-bottom interest rates and with unemployment at 3.8 percent, where is the inflation? It’s a whodunit that hangs heavily over the Federal Reserve.

Not only is this clouding the central bank’s monetary policy decisions, it begs questions about how policy makers should pursue their mandates for maximum employment and stable prices. That’s a big reason why the Fed has just kicked off a year-long review of how best to achieve those goals.

“It’s almost surely true that inflation is less tightly linked to what’s going on in the real economy than it used to be, and that matters a lot,” said Jeffrey Fuhrer, director of research at the Boston Fed.

The latest data only add to the puzzle of absent price pressures, with a key measure of underlying U.S. inflation unexpectedly easing in February.

The Mystery

Since the Fed set 2 percent as its explicit inflation target in January 2012, its favorite gauge of prices -- the personal consumption expenditures price index -- the has averaged just 1.4 percent. Exclude volatile food and energy prices, and it noses up to 1.6 percent.

To be fair, unemployment was high for some of those years, but even in the months since March 2017 when joblessness fell below 4.5 percent, core inflation has averaged 1.7 percent. Moreover, the puzzle pre-dates the recession. Going back to 1993, that gauge has averaged 1.8 percent.

So What?

Is this really such a bad thing? For those who remember the 1970s and ’80s, inflation a few ticks below the Fed’s objective seems like a good problem to have. Still, low inflation can be troublesome.

Along with lukewarm rates of economic growth, below-target inflation is keeping interest rates historically low. That makes it harder for the Fed to fight recessions because there’s less room to cut rates before hitting zero.

Low inflation can also corrode a central bank’s most important asset: credibility. It’s widely accepted that public faith in the Fed’s commitment to hitting 2 percent can help meet that goal. Missing persistently to one side risks undermining that confidence.

“It could potentially be damaging to credibility,” said Brent Meyer, an economist at the Atlanta Fed. “If inflation expectations fell below the target level, that would, in theory, make it harder for central bankers to hit that target. And that could be a significant issue.”

Explanations

There’s a blizzard of theories aiming to solve the riddle, each with its own set of monetary policy implications. Most economists believe the answer lies in some combination of these ideas, rather than a single culprit.

1. Slack

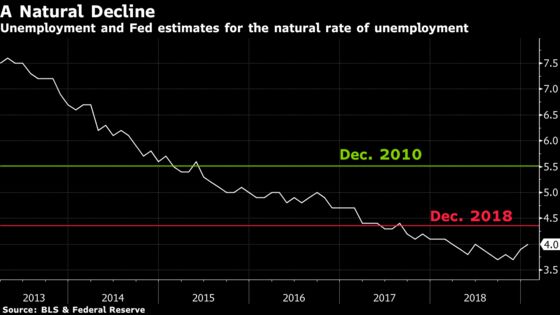

One bundle of theories holds that the labor market simply isn’t as tight as most economists believe. It may be, for example, that the level at which unemployment provokes higher inflation is lower than estimated. Fed officials put this threshold at about 4.4 percent, but if it were, say, 3.9 percent, the inflation mystery might disappear.

A related argument focuses on labor market slack. Unemployment is low, but the numbers only count people actively looking for work. Employers can hire people off the sidelines, which has been happening a lot in the U.S., suggesting hidden job-market slack.

Then there’s international labor slack. Many economists estimate that opening up trade to nations like China has added at least 1 billion workers to global labor supply.

Such explanations suggest officials can push unemployment lower than in the past, up to a point. If it falls low enough, or if hidden slack is used up, the labor market may yet generate significant inflationary pressure.

2. Secular Disinflation

Economists see a variety of longer-run structural changes that may put downward pressure on inflation. For example, in an aging population older people save more and spend less; baby boomer retirements drive down average compensation. The collapse of organized labor, growing concentration among employers and exposure to international trade represent others.

Technology is also a popular suspect for lowering businesses costs and allowing companies to raise profits even as prices rise modestly, or even fall. There’s just one major hole in that argument. If true, labor productivity ought to have risen significantly when in fact it has been sluggish for years.

If any one, or a combination, of the offerings in this category were the culprit, the implication for monetary policy would be straightforward: As long as the phenomenon persists, keep rates a bit lower than you otherwise would.

3. Anchored Expectations

Our last category seems to be the Fed’s favorite person-of-interest. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell told Congress on Feb. 26 that “inflation expectations are now the most important driver of actual inflation.”

The theory suggests inflation outcomes are heavily influenced by what the public expects inflation will be, and those expectations can be anchored if the public believes the central bank will deliver on its target.

Proponents point out that U.S. inflation stopped responding strongly to unemployment in the early 1990s. That aligns with the widespread acceptance that the Fed was committed as an institution to keeping inflation at bay. Indeed, it’s been well behaved amid recent low unemployment and didn’t fall as much as expected when the jobless rate hit 10 percent in 2009. It seems inflation is not so much being held down as it’s being held in place.

Still, the case is largely circumstantial. Economists have only a loose understanding of how this functions in practice. Fuhrer at the Boston Fed is skeptical that in the real world people think about their expectations for long-run, aggregate inflation when setting prices.

The expectations theory, however, offers central bankers an attractive scenario. Once expectations become successfully anchored, they can worry less about ups and downs in the business cycle throwing inflation out of whack -- unless inflation expectations, themselves, drift off target.

And that’s exactly what’s begun to vex the Fed -- that the long stretch of sub-2 percent inflation may have caused expectations to decline. Thus its framework review this year.

“What we’re looking at is a way to more credibly achieve our existing symmetric 2 percent inflation target,” Powell told lawmakers.

To contact the reporter on this story: Christopher Condon in Washington at ccondon4@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull, Sarah McGregor

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.