Kudlow’s War Bonds Are Coming, But in a Plain Vanilla Wrapper

Larry Kudlow’s War Bonds Are Coming But in a Plain Vanilla Wrapper

(Bloomberg) -- President Donald Trump’s top economic adviser Larry Kudlow may get the war bonds he wants as the U.S. swells its debt pile to levels unlike anything seen since World War II.

They won’t actually be called war bonds, an idea Kudlow says he discussed with Trump and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. They won’t actually be any different than the type of securities already being auctioned -- beside a reboot of a maturity that was previously shelved -- but they will be part of what the president calls his war with the “invisible enemy” of Covid-19. And they likely will cause the amount of U.S. debt to match the size of the economy for the first time since the 1940s.

Mnuchin is already cranking up debt issuance to fund the widening budget deficit in the wake of a $2.2 trillion stimulus package, the largest ever passed. The aid was expected to keep the economy running for another eight weeks or so, according to Mnuchin’s own estimate when the law was enacted.

“The sheer amount of debt coming is really war-time sort of funding,” said John Briggs, head of strategy for the Americas at Natwest Markets.

The tenors of the securities are expected to match what the government now offers, which are Treasuries with maturities out to 30 years, as well as a return of 20-year bonds.

No 50-Year

Mnuchin has heeded guidance from Treasury’s debt advisory committee, which for years had stressed the U.S. should avoid bonds with longer maturities in order to best serve taxpayers. He has studied the potential of ultra-long bonds twice, with the possibility of a 50-year security re-emerging amid the current crisis.

However, Mnuchin’s team concluded that the time isn’t right for ultra-long bonds, despite pressure from some corners of the administration.

“We are going to be auctioning off 30-years and 20-years -- buy one of each, and it’s the 50-year,” Mnuchin quipped last week when pressed in a CNBC interview on the prospect of war bonds.

The 20-year bond -- which Mnuchin announced in January he would re-issue after a three-decade hiatus -- may be touted as Treasury’s big war-funding splash, said Briggs.

“That way they will also be financing the rising deficit at the cheapest cost for taxpayers,” he said.

The government already has been selling Treasury bills -- debt maturing in one year or less -- at a fever pitch, and boosted the size of recent three-, 10- and 30-year auctions. More is coming, with details on plans for long-term issuance slated to come at Treasury’s May 6 quarterly refunding announcement.

Swelling Deficit

The extra spending combined with a likely deep recession will add $1.6 trillion to the deficit just in the next two quarters, Briggs’s Natwest colleague Blake Gwinn estimates. He sees $950 billion of that financed with Treasury bills and $250 billion via the Fed rolling over its securities into new ones. Treasury will have to sell notes and bonds to fund the remaining $400 billion.

The fiscal 2020 deficit that needs to be funded will be four times as large as last year’s at $3.8 trillion, or almost 19% of gross domestic product, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a non-partisan group. While few in Washington see a need to prioritize fiscal prudence right now, given the economic damage being done by the virus, the CRFB warns that an unsustainable situation is brewing and corrective actions will be needed one day.

“Putting long-term deficit reduction measures in place sooner rather than later would allow policy makers to phase in changes more gradually and give those affected more warning and ability to prepare,” the group wrote on its blog.

The U.S. has used special war bonds in the past, drawing on patriotism to fund military and counter-terrorism operations. Americans lent their government money through purchases of Liberty Bonds in World War I and War Bonds in World War II. In 2001, Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill introduced “Patriot Bonds” to help finance the fight against terrorism after the Sept. 11 attacks.

All of those special offerings were savings bonds, or securities that are not tradeable or auctioned like standard Treasury debt. But this time, while Americans may be patriotic and united in a desire to fight the virus’s effects, millions of them are unemployed with little spare cash to lend the government.

War bonds were also used last century to curb consumer spending and keep a lid on inflation. That’s the opposite of what is needed now -- especially with consumer spending making up about two thirds of GDP.

Haven Appeal

Economists at JPMorgan Chase & Co. say GDP will shrink an annualized 40% in the second quarter. The dire outlook should bolster demand from investors for the safety of Treasuries.

“There is a huge amount of debt that is coming in the second quarter,” said Tom di Galoma, managing director of government trading and strategy at Seaport Global. “But there remains a lot of demand for government securities given fund managers remain concerned about the fate of the equity market. There may be some back-up in yields, but not very much.”

The Federal Reserve’s purchases of Treasuries, being done to ensure the smooth functioning of the bond market after it became dislocated amid the pandemic panic, will help Mnuchin by keeping yields lower than they would be otherwise. During the World War II era, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had an understanding with then-Fed Chairman Marriner S. Eccles that long-term rates -- then at about 2.5% -- would be kept low.

The 10-year Treasury yield is currently trading at around 0.75%, compared with 1.92% at the end of 2019.

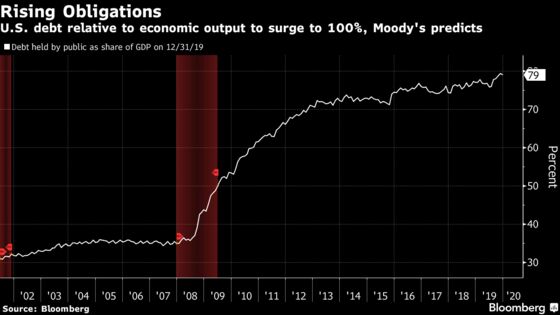

U.S. debt relative to the nation’s GDP is on course to reach 100% sometime next year, comparable to levels during the World War II era, says Mark Zandi, Chief Economist at Moody’s Analytics. Before the global financial crisis, it was 35% of GDP.

“There’s a very fine distinction between a ‘war bond’ and a 10-year Treasury that is yielding what it is now,” Zandi said by phone. “The difference is really in name only.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.