U.S. Catches Kremlin Insider Who May Have Secrets of 2016 Hack

In the days before Christmas, U.S. officials in Boston unveiled insider trading charges against a Russian tech tycoon.

(Bloomberg) -- In the days before Christmas, U.S. officials in Boston unveiled insider trading charges against a Russian tech tycoon they had been pursuing for months. They accused Vladislav Klyushin, who’d been extradited from Switzerland on Dec. 18, of illegally making tens of millions of dollars trading on hacked corporate-earnings information.

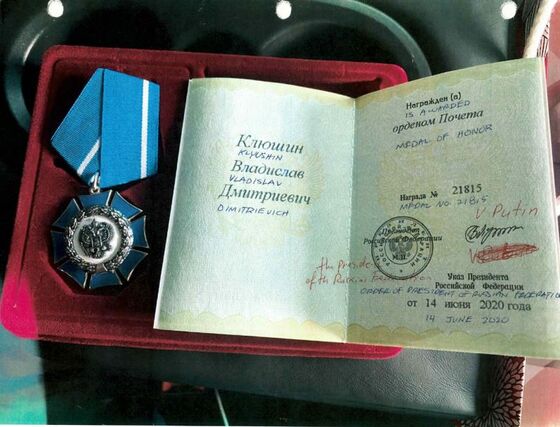

Yet as authorities laid out their securities fraud case, a striking portrait of the detainee emerged: Klyushin was not only an accused insider trader, but a Kremlin insider. He ran an information technology company that works with the Russian government’s top echelons. Just 18 months earlier, Klyushin received a medal of honor from Russian President Vladimir Putin. The U.S. had, in its custody, the highest-level Kremlin insider handed to U.S. law enforcement in recent memory.

Klyushin’s cybersecurity work and Kremlin ties could make him a useful source of information for U.S. officials, according to several people familiar with Russian intelligence matters. Most critically, these people said, if he chooses to cooperate, he could provide Americans with their closest view yet of 2016 election manipulation.

According to people in Moscow who are close to the Kremlin and security services, Russian intelligence has concluded that Klyushin, 41, has access to documents relating to a Russian campaign to hack Democratic Party servers during the 2016 U.S. election. These documents, they say, establish the hacking was led by a team in Russia’s GRU military intelligence that U.S. cybersecurity companies have dubbed “Fancy Bear” or APT28. Such a cache would provide the U.S. for the first time with detailed documentary evidence of the alleged Russian efforts to influence the election, according to these people.

Klyushin’s path to the U.S. — his flight from Moscow via private jet, his arrest in Switzerland, and his wait in jail as Russia and the U.S. competed to win his extradition — is described in U.S., European and Swiss legal filings, as well as in accounts of more than a half-dozen people with knowledge of the matter who requested anonymity to speak about Moscow’s efforts and its causes for concern.

According to these accounts, Klyushin was approached by U.S. and U.K. spy agencies in the two years before his exit from Russia and received heightened levels of security in Switzerland. He also missed a final chance to appeal his extradition, an omission that baffled many observers in Moscow. His transfer to the U.S. represents a serious intelligence blow to the Kremlin, several of the people said, one that would deepen if Klyushin decides to seek leniency from U.S. prosecutors by providing information about Moscow’s inner workings.

Three of the people added that they believe that Klyushin has access to secret records of other high-level GRU operations abroad. Russian military intelligence agents in recent years have been linked to a series of hacking attacks as well as the attempted chemical poisoning assassination of dissident ex-GRU colonel Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the U.K. in 2018. Russia has denied involvement.

Indications of Klyushin’s vantage point are peppered throughout U.S. filings. His IT firm, M-13, worked for the Russian presidency, government and ministries, according to his insider trading indictment. Among his subordinates was a former military intelligence official named Ivan Yermakov, who is charged alongside Klyushin in the indictment. Yermakov is also a defendant in a 2018 indictment from U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team that accuses him and 11 other Russians of hacking into Democrats’ computers systems. That case has yet to be resolved because its defendants remain outside the U.S., but prosecutors could pursue and expand that case if new information presents itself.

Klyushin’s attorney in Switzerland, Oliver Ciric, said he doesn’t know anything about what, if any, documents his client may have. Ciric said in an interview that his client was sought by U.S. authorities because they believe he has inside information on Russia’s 2016 election hacking that he may provide to avoid decades behind bars on the insider trading charges. Ciric added that Klyushin says he is innocent of insider trading and of “hypothetical election meddling.”

Klyushin’s U.S.-based lawyer Maksim Nemtsev, writing in a bail application, said his client “intends to challenge the government’s case in a lawful, professional and principled manner.” Klyushin appeared for his arraignment in Boston federal court on Monday via video link from lockup, wearing a white T-shirt and speaking through an interpreter. The judge postponed the matter until Wednesday, however, asking Klyushin's lawyer to file additional paperwork. Nemtsev didn’t respond to a request for additional comment.

Any exposure of Russian hostile behavior by law-enforcement officials risks inflaming relations just as President Joe Biden’s administration is engaged in delicate efforts to dial back tensions with Putin. The latest unease is sparked by Russia’s massive military buildup near Ukraine, as U.S. intelligence indicates the threat of a Russian invasion of its ex-Soviet neighbor. U.S. and Russian negotiators are due to meet Jan. 9 in Geneva to discuss the Kremlin’s demands for legally binding guarantees of a halt to NATO eastward expansion.

Klyushin’s extradition suggests that federal law enforcers haven’t dropped their pursuit of “the radical violation of U.S. sovereignty during the 2016 elections that involved criminal behavior,” according to Michael McFaul, who was a U.S. ambassador to Russia during the Obama administration.

“You may be seeing the signs that they are continuing to pursue this case, with real big implications for exposing in even greater detail what the Russians did to influence the outcome of our election,” McFaul said. He added that Klyushin’s extradition is a “serious concern” for the Russian government. “It underscores the risk that anybody, billionaires or others close to the Russian state, face when they break American laws if they travel abroad,” he said.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov didn’t respond to a request for comment. Russia’s Foreign Ministry declined to comment.

Top Cyber Clients

Klyushin’s M-13 promised a range of information tech services, including social media monitoring and cybersecurity, according to U.S. filings that cited the company’s website. It offered to probe its clients for cyber weaknesses by simulating attacks — known as penetration testing — and also by mounting targeted ongoing attacks known as advanced persistent threats, or APT. The company provided a media-monitoring system, Katyusha, to the Kremlin and Defense Ministry, as well as services to other government institutions such as the Prosecutor General’s Office, National Guard and Moscow city hall, according to Russian state contract records.

For his part, Klyushin amassed “immense wealth,” U.S. prosecutors wrote. They cited his ownership of a three-million-pound ($4 million) yacht purchased in the U.K., a London apartment and millions of dollars in cash.

Klyushin is one of several high-level individuals in Russia’s cyber sector who have been at the center of drama in both Russia and the U.S. Two of these Russians provided information several years ago that led to U.S. indictments of Russians for alleged election manipulation, Bloomberg has previously reported.

One was arrested in Russia in 2016 and jailed on treason charges. The other, Russian cybersecurity entrepreneur Ilya Sachkov, was close to Klyushin, three of the people said. Sachkov provided the U.S. government with information that helped it identify the 12 GRU agents it accused of involvement in the hacking of Democratic servers, including Klyushin’s senior employee Yermakov, people familiar with the matter have previously told Bloomberg. Russia has repeatedly denied meddling in U.S. elections. Sachkov was arrested in Russia in September and is jailed awaiting trial on unspecified treason charges.

U.S. and British intelligence tried twice to recruit Klyushin, according to Ciric, the attorney in Switzerland. U.S. intelligence attempted to engage him in summer 2019 in the south of France and British intelligence approached him in March 2020 in Edinburgh, Ciric said.

Klyushin memorialized that second meeting in a note he wrote a few weeks after the encounter and saved on his computer, according to Ciric. It took place at Edinburgh’s airport, as Klyushin was taking a flight back to Russia, according to the memo, which was submitted to the Swiss courts as part of his appeal against extradition. Klyushin wrote that two British intelligence agents — one from MI5 and the other from MI6 — spoke to him for a few minutes in a room where he was led after a passport check.

The two Russian-speaking officers, a man and a woman, asked him if he would “cooperate” with U.K. secret services and took his phone number to set up a meeting on his next trip to London planned for May, according to the previously unreported document, which was reviewed by Bloomberg. Klyushin wrote that while he didn’t respond to the cooperation offer, he said he would be willing to see the agents again to discuss selling M-13 products to British intelligence.

It’s unclear whether Klyushin informed Russian intelligence about the U.S. and British recruitment efforts. The U.K. Foreign Office, which handles media inquiries for MI6, declined to comment.

Family Ski Vacation

The U.S. learned that Klyushin was traveling in the spring of 2021 to Switzerland, which has a joint extradition agreement with the U.S., and issued an arrest warrant on March 19. Ciric said he believes the U.S. learned of the trip “a few days before” by illegally hacking his client’s phone, noting that Klyushin’s Switzerland itinerary and other personal information and photos from the device made their way into case materials. The Justice Department didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Two days later, a private jet flying from Moscow touched down at Sion Airport in southwestern Switzerland. Klyushin, his wife and five children stepped off the plane. A helicopter was standing by to whisk them to the exclusive ski resort of Zermatt, according to U.S. filings.

Shortly after leaving the plane, Klyushin was detained by Swiss police. He was taken hours later to a prison in nearby Sion.

His wife and kids continued to the ski resort along with a business partner and his daughter, according to two people familiar with the matter. The party returned to Moscow on March 29, after almost 10 days at a luxury chalet, these people said.

News of Klyushin’s detention provoked immediate action in Moscow: On April 7, Russia filed papers with Switzerland accusing Klyushin of fraud and seeking his extradition to face charges in his home country — a strategy the country has attempted to use in recent years when nationals have been accused abroad.

Three of the people familiar with the matter characterized Klyushin’s departure to Switzerland as a huge failure of Russian secret services after his contacts with intelligence agencies, and they said they expect the top officials responsible to lose their jobs.

The Swiss held Klyushin under high security, alone in a cell, according to his lawyer. He was accompanied by as many as 10 police, most of them heavily armed, on his only trip between the jail and the courthouse in Sion in April — unprecedented security measures for white-collar cases in Switzerland, according to his lawyer.

While in the Swiss prison, Klyushin told Bloomberg, through his lawyer, that he didn’t know why he was arrested in March and not before, saying that he had previously traveled freely to Europe. He blamed his detention on an “operation mounted by the U.S. in cooperation with Swiss authorities” to obtain “certain confidential information the American authorities consider” he has.

The U.S. filed its own extradition bid for Klyushin nearly two weeks after Russia, on April 19.

By then, a U.S. federal grand jury had already handed up indictments charging Klyushin and Yermakov — identified in some in filings as Kliushin and Ermakov — and three other alleged conspirators. Filed on April 6, the sealed indictment of Klyushin accused the group of hacking into the servers of two online agencies used by U.S. publicly traded companies to file their quarterly reports a day or two before they’re released. With an advance look at the results, the men bet on or against stocks including International Business Machines Corp., Snap Inc., Tesla Inc. and Microsoft Corp., netting them illegal profits of $82.5 million, according to the indictment. Klyushin faces a recommended sentence of 20 years in prison, though the charges carry a maximum penalty of 50 years.

Headlining the investigation was B.J. Kang, an FBI special agent famous for bringing in convicted fraudster Bernie Madoff and inside trader Raj Rajaratnam. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has also filed charges.

Diplomatic Snarl

In August, Switzerland rejected Moscow’s extradition request.

Soon after came an international diplomatic snarl that speaks to Klyushin’s importance to Moscow. Following a Russia-U.S. presidential summit in June, the two sides were negotiating to swap two former U.S. Marines imprisoned in Russia, Paul Whelan and Trevor Reed, for two Russians held in the U.S., including notorious arms dealer Viktor Bout. But after Switzerland declined to hand Klyushin back to Russia, the Kremlin demanded that his name be added to the swap, according to three people with knowledge of the issue. That derailed the potential exchange, which remains blocked, these people said.

There is no link between Klyushin and the return of Reed and Whelan to the U.S., said a U.S. National Security Council spokesperson. The U.S. government continues to press for their release, the spokesperson said.

Klyushin’s chances of a trip to the U.S. grew when the Swiss supreme court refused to consider an appeal against his extradition, saying it had no reason to challenge the legitimacy of the U.S. courts. The panel made its ruling in a Dec. 10 session, which was communicated to Ciric on Dec. 16, according to him and the court.

Once Switzerland’s top court refuses an appeal, detainees can be handed over within two to four days, Ciric said in an interview a month before the ruling.

That left Klyushin with a brief window to make a last-ditch appeal of his extradition — a request to the European Court of Human Rights, based in Strasbourg, France. However, his attorney filed that request in a way that took days, rather than hours. That led three of the people close to the Kremlin and Russian security services to conclude that Ciric may have facilitated a transfer to U.S. custody on his client’s instructions. Ciric didn’t respond to a request for comment on the timing of the ECHR appeal.

Once Ciric had received the supreme court’s decision, the Geneva lawyer filed a petition with the ECHR, reviewed by Bloomberg. The letter, dated Dec. 16 and labeled in French as “urgent,” asked the court to suspend the extradition order.

A day later, on Dec. 17, Ciric emailed Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. “We have urgently filed an application with the European Court of Rights” requesting it “immediately put on hold the extradition of Mr. Klyushin since this action will undoubtedly cause irreparable damage,” Ciric wrote in the previously unreported letter, which was reviewed by Bloomberg.

A spokesman for the Strasbourg court said emergency requests are typically faxed or emailed to ensure immediate delivery — which in this instance may have made all the difference. On Dec. 18, U.S. agents took custody of Klyushin at Zurich airport and flew him to face trial in the U.S.

Klyushin’s request was received by the ECHR only on Dec. 22, according to the Strasbourg court’s spokesman. By then, Klyushin had already been in the U.S. for four days.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.