If Matteo Salvini Can Win Here, He Can Win Anywhere

If Matteo Salvini Can Win Here, He Can Win Anywhere

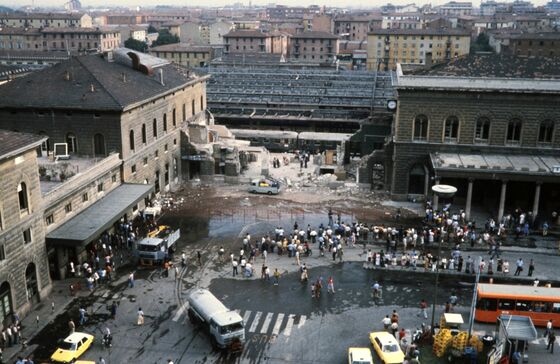

(Bloomberg) -- Time stands still above Bologna’s train station where the clock outside is set at 10:25 a.m. The names of the “Victims of Fascist Terrorism” are listed on a plaque in the waiting room where a bomb killed 85 people on a sweltering August morning in 1980.

What looks like litter on the floor is a splatter of cards featuring the images of saints left for the victims of one of the darkest chapters in Italy’s violent postwar history, when far-left and far-right extremists went on a killing spree known as the Years of Lead. After almost four decades of false trails, who really commissioned the attack remains the subject of many a conspiracy theory.

The massacre further calcified the city, and the region’s, long-held abhorrence of the right. This bastion of the resistance movement against dictator Benito Mussolini, home to good food (tortellini) and fast cars (Lamborghini) has only ever really been run by communists, socialists, or the center-left.

But now its allegiance is being tested by Matteo Salvini’s relentless campaign to convince Emilia-Romagna to switch tribes in regional elections next month. If he manages, it answers the most important question in Italy right now: Can the nationalist firebrand and the nation’s most popular politician be stopped from clawing his way to become prime minister?

A victory for his anti-migrant League, and allies including Giorgia Meloni’s far-right Brothers of Italy, would see him seize the jewel in the left’s crown and mark a watershed moment. If he can win here, he can win anywhere.

In Bologna, an anti-Salvini resistance has taken form in the shape of the so-called Sardines. Four locals decided that if Salvini could draw big crowds, then those against him had to attract even bigger ones. So now, from Parma ham’s birthplace to Federico Fellini’s Rimini, thousands of protesters squeeze into historic squares like in a tin of canned fish.

A League conquest in this cozily left-leaning stronghold could rock the national government, an already-fragile coalition of the center-left Democratic Party and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement.

Inside the city’s establishment is a steady trickle of complaints uttered “sotto voce” about complacent rulers who take its prosperity for granted and rely too heavily on Europe’s oldest university, Bologna’s gastronomic excellence and good looks to draw talent and tourism. Its business-rich fabric makes it Italy’s third-wealthiest city in terms of income per person. This is where Ducati motorbikes get made.

There’s a smugness about Bologna—nicknamed the “fat one, the red one, the learned one”—that harks to its culinary, political and historic past. The person who put it best was the singer-songwriter Francesco Guccini, a contemporary of Bob Dylan, who in a song referred to the town as “an old lady with slightly flabby hips,” vulgar and arrogant.

It was a ballad released at a sensitive time, the year after the Bologna bombing, and today almost sounds like a warning. The same place that abolished slavery as early as 1256 and fought fascism is now susceptible to the anti-immigration drum roll of Salvini and ready for a change of scene.

“Bologna is a bit hypocritical,” said Alberto Canè, a financial adviser with Allianz Bank. “The old money, the entrepreneurs, the families who’ve inherited wealth, they’d like to vote for the League but don’t say so publicly.”

At a café under one of the city’s many streams of picturesque porticoes, 21-year-old Nicolò Malossi sees “a silent majority” behind Salvini’s League. An engineering student who heads the party’s local youth branch, Malossi denounces the pernicious effects of globalization that has seen China’s textile explosion undercut the proud “Made in Italy” brand.

“Unfair competition threatens us, our Parmesan and our Parma ham,” said Malossi, who recalled being labeled a Nazi when out canvassing. “Uncontrolled immigration is also hurting our economy, there’s a risk migrants go into crime when there’s no work for them.”

Nationally, Salvini suffered a blip in support after he ditched the government in the summer in a failed bid to force an election he hoped would see him promoted from deputy premier to premier. But since then, he has been on a run, with polls showing a third of voters back him. In Emilia-Romagna, surveys see a narrow race. The latest SWG survey pointed to a slight advantage for the League’s candidate over the outgoing center-left regional president.

Canè himself wants less taxes and fewer migrants: two points Salvini is hammering home everywhere he goes in the region. And as for the Sardines, Salvini’s sneerily defiant. “Bring them on,” he said while campaigning in Bologna on Dec. 1. “They bring me joy, and I thank them for their service.”

For Canè’s clients, the thought of voting for Salvini is still a bit taboo. He declined to say whether he’ll cast a ballot for the League, citing his professional role. He does want Salvini to strike a more moderate tone, to win local voters.

At the ornate 14th-century Palazzo della Mercanzia housing the Chamber of Commerce, its 61-year-old president showed off what he calls “the Harry Potter Room,” decorated with the insignia of medieval trades. Valerio Veronesi hands a brochure of ancient recipes blessed by the Learned Confederation of the Tortellino to visitors, and talks about “a wind of change.”

“It’s blowing in only one direction—the center-right,” said Veronesi, who also declined to reveal his political sympathies. “People are tired of the status quo.”

Whether the Bolognesi will break a life-time habit of voting with the left remains to be seen. The city is full of mysteries, from who was really behind the 1980 atrocity to how the town was once something of a little Venice. There’s a window, literally a window in a wall, offering a view of a long-hidden canal running between ancient ocher-colored houses.

Once a well-kept secret, it’s now part of a well-trodden tourist trail that has spawned Airbnb rentals in the city center and forced students to find cheaper digs away from the university—whose most famous professor was Umberto Eco, author of the 1980 novel “In the Name of the Rose.”

Mayor Virginio Merola, 64, maintains Bologna is still “avant-garde,” as he chain-smokes cigarettes of the brand favored by Mao Zedong, given to him on a trip to China, from his corner office in the sprawling city-hall complex. “We’re not complacent, we’ve always accompanied change,” insisted Merola, now on his second mandate.

He acknowledged, though, that the left is in the danger zone: “We’re too scared of Salvini. He isn’t the prime minister, but he’s treated as such.”

Efforts to keep alive the flame of the anti-fascist legacy are waning even as there are signs that point to a disturbing undercurrent in Italy. Police uncovered a disturbing plot to create a new Nazi Party and the number of recorded hate crimes have almost doubled since 2014.

Yet these days The Resistance Museum, housed in a former convent, sees only 10 or so visitors a day. Even Bologna is wavering, on the brink of turning a new leaf.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Flavia Krause-Jackson at fjackson@bloomberg.net, Caroline Alexander

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.