India’s Caste System

India’s caste system was formalized in a legal treatise called Manusmriti, dating from about 1,000 B.C.

(Bloomberg) -- For generations of Indians, the ancient code of social stratification known as the caste system has defined how people earn a living and whom they marry. Despite reform efforts, deep-rooted prejudices and entitlement hold firm among higher castes, while those on the lowest rungs still face marginalization, discrimination and violence. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has a strategy that purports to look beyond caste and focus on improving the lot of all Indians. His approach has won overwhelming backing from voters, but critics say it risks exacerbating the plight of the most disadvantaged.

The Situation

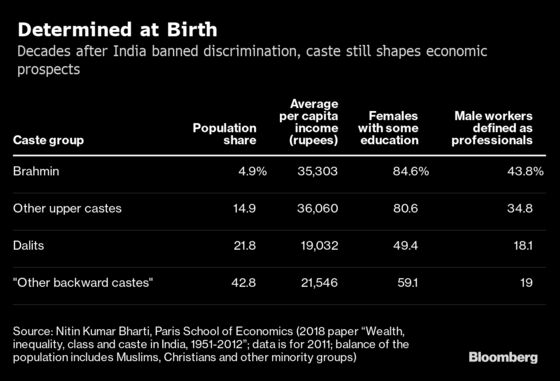

Seven decades ago, the founders of postcolonial India outlawed caste discrimination and enshrined affirmative action in the constitution. That included reserving government jobs and places in higher education for Dalits — a group at the bottom rung of the caste system who now number more than 200 million. Yet caste remains a significant factor in deciding everything from family ties and cultural traditions to educational and economic opportunities, especially in small towns and villages, where more than 70% of Indians live. Nearly a third of Dalits make less than $2 a day, and many don’t have access to education or running water. Most menial jobs are carried out by Dalits; few office jobs are. Hate crimes against Dalits have proliferated in recent years, prompting criticism of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party for allegedly stoking social divisions. The party is the natural home for Hindu hardliners, some of whom have attacked Muslims for eating beef and lower-caste Hindus over their links to the beef trade. (Hindus consider cows sacred.) Dalits have taken to the streets by the tens of thousands to demand protection of their rights. Yet, for the second straight election, Modi led the BJP to a resounding victory in 2019, even securing a larger share of Dalit votes. Parties with policies aimed in particular at promoting lower castes were trounced, as Modi’s appeal to a common Hindu heritage trumped caste consciousness.

The Background

While there’s disagreement over its origins, the caste system was formalized in a legal treatise called Manusmriti, dating from about 1,000 B.C. The text defined karma (actions) and dharma (duty) for Hindus, who today represent 80% of India’s population. In it, society was divided into four strictly hierarchical groups known as varnas: the Brahmins — priests and other intellectuals — at the top; then the Kshatriyas, or warriors; then the Vaishyas, or traders; and lastly the Shudras, those who did menial labor. The texts laid down laws on marriage, property and even food. For instance, if a Brahmin consumed food prepared by a Shudra, he’d be born a pig in his next life. The system has since evolved to include some 3,000 castes and 25,000 subcastes. Over time, as social segregation and caste prejudice deepened, another layer of Shudras emerged at the base of the pyramid: Dalits, meaning “divided, split, broken, scattered” in classical Sanskrit. Not only were they barred from sharing food with or marrying people from higher castes, some couldn’t even brush the shadow of a Brahmin. They got their other name — “untouchables” — because their mere touch could supposedly defile. Not all of them are Hindu; Dalit Muslims, many descended from lower-caste Hindus who converted to Islam in an effort to escape the repression of the caste system, continue to face prejudice from non-Dalit Hindus and Muslims, a 2016 study found.

The Argument

Modi’s stated aim is to make traditional castes irrelevant. He says there are now just two castes: the poor and those who will contribute to eradicating poverty. It’s a message that resonates with voters desperate for faster progress in a country where salaries are less than one-quarter of those in China. Skirting the issue of caste, Modi’s critics say, risks allowing prejudice to fester and violence against Dalits and Muslims to thrive. The strategy may also mask the economic plight of lower castes. A study in 2018 by the Paris School of Economics concluded that they were failing to close the gap with other groups, and that inferior education means they’re likely to fall further behind. Numerous studies point to entrenched caste prejudice in rural India, yet there are signs of change as more Indians move to cities (half will be urban dwellers within two decades) and younger people (almost half the population is under 25) show greater tolerance. While just 5% of Indian marriages are between different castes, a study in 2019 identified a “generational shift” in attitudes, with almost a quarter of profiles on matrimonial websites showing an openness to inter-caste marriage.

The Reference Shelf

- History of the caste system and its impact on India today by Manali S. Deshpande.

- A Paris School of Economics paper on caste and inequality by Nitin Kumar Bharti.

- Dr. B R Ambedkar’s The Annihilation of Caste, an undelivered speech written in the 1930s and later self-published.

- A story on India counting caste numbers and another on unemployment woes stoking a voter backlash.

- How caste has affected economic opportunities and social mobility.

- Poisoned Bread: An anthology of Dalit literature edited by Dr. Arjun Dangle.

- A QuickTake on Hindu nationalism.

To contact the editor responsible for this QuickTake: Grant Clark at gclark@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.