In States That Didn’t Expand Medicaid, Voters Might Do It Anyway

In States That Didn't Expand Medicaid, Voters Might Do It Anyway

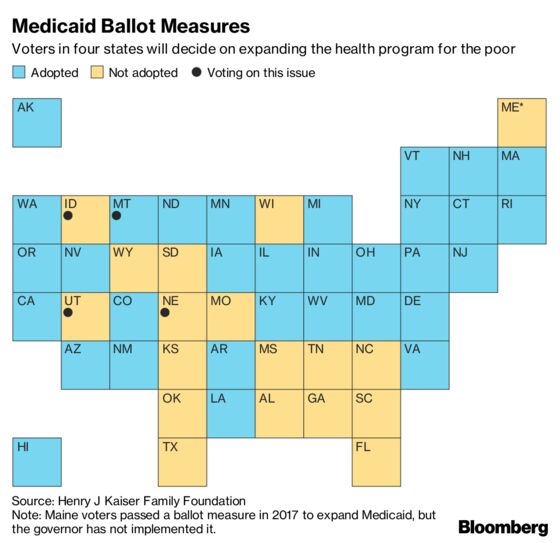

(Bloomberg) -- For years, elected leaders in conservative states have resisted expanding Medicaid, the government health program for low-income Americans. Now voters in four of those states will decide the question directly.

Ballot initiatives in Idaho, Utah, Nebraska, and Montana will test whether there’s a disconnect between politicians and voters over a program that insures 1 in 5 Americans at an annual cost of more than half a trillion dollars to federal and state governments. Advocates behind the measures in states carried by President Donald Trump in 2016 aim to distance Medicaid expansion from the law that makes it possible: the Affordable Care Act.

“This isn’t Obamacare -- this is Medicaid,” said Ray Ward, a Republican state lawmaker and physician from outside Salt Lake City. Ward supports widening eligibility for Medicaid in Utah, and says many of his constituents do too. While solidly Republican, his district is “not an angry sort of Tea Party district,” he said.

Views of the ACA have hardened since it became law in 2010, especially among Republicans: 70 percent consistently find it unfavorable, according to polls by the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health-policy research group.

Prior to Obamacare, most states limited Medicaid to the very poor, blind, disabled, and pregnant women and children. Today, states can extend the program to adults earning up to about $17,000 a year for an individual, and 33 states have. Federal money pays most of the bill, but states still have to cover about 10 percent.

Nationwide, about 2.2 million uninsured people who can’t get subsidized coverage would be eligible if the 17 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid were to do so, according to Kaiser.

In the ballot initiatives, local advocates have joined with with professionals from the Fairness Project, a labor-backed group. It’s run campaigns for higher wages in California, Colorado and elsewhere. In addition to the Medicaid initiatives this year, the Washington-based group is supporting ballot measures for minimum wage increases, paid sick time and other progressive causes in seven states, from Arkansas to Michigan.

Ballot initiatives “are so powerful because they strip away from the partisanship and the tribalism that dominates so much of our politics,” said Jonathan Schliefer, executive director of The Fairness Project. “When it comes to health care, the biggest gap isn’t between Republicans and Democrats. It’s between politicians and everyone else,” he said.

On the other side of the political spectrum, local affiliates of Americans for Prosperity, backed by the billionaire Koch brothers, are opposing the ballot measures in Utah and Nebraska. David Barnes, AFP’s policy manager, said the costs may exceed what states project and that Medicaid dollars should be dedicated to vulnerable populations, not working-age adults.

Barnes said he’s not surprised that even in conservative states some lawmakers want to expand the program. “It’s just so difficult for people, for state legislators, to look at this and not think there’s just free money coming from Washington, and they feel like they should go try to grab it,” he said.

In Montana, voters will decide whether to extend the Medicaid expansion that began in 2016 under Democratic Governor Steve Bullock. That ballot question would fund Medicaid with a $2-a-pack cigarette tax that tobacco interests have raised millions to oppose.

In some states, the effort to expand Medicaid has found some surprising advocates. One is Christy Perry, a Republican state representative in Idaho. She co-owns a gun shop in Boise and is a lifetime member of the National Rifle Association. In a recent unsuccessful bid for Congress, her campaign website warned that the federal government in Washington wants “our guns, our property, and our rights.”

Yet Perry is also co-chair of Idahoans for Healthcare, a group devoted to passing the Medicaid expansion. She was frustrated after the legislature failed for several years to do it. Perry argues that Idaho already pays for health care for the poor through state safety-net programs, while missing out on federal funds that other states that expanded Medicaid got.

“This is not about party, this is not about politics, this is about people,” Perry said. She cites the story of an uninsured Idaho woman who died after an asthma attack in 2015. Perry’s own mother was briefly uninsured and discovered she had colon cancer only after turning 65 and getting Medicare. She was treated successfully.

The Idaho initiative has support from the medical industry, the state sheriff’s association and business groups. Lieutenant Governor Brad Little, who is favored to win the governor’s race, has said he won’t stand in the way if voters approve Medicaid expansion.

While Montana and Utah’s initiatives include funding, Idaho’s ballot question doesn’t. “There’s no reference to how this will be paid for,” said Fred Birnbaum, vice president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, which opposes the initiative. He said lawmakers represented the will of Idahoans when they blocked earlier attempts at expansion, and could still stand in the way of funding it.

The blueprint for this year’s initiatives was drawn in Maine. Last year, 59 percent of voters approved expanding Medicaid over the objections of Republican Governor Paul LePage, who has said he would go to jail “before I put the state in red ink” for the program. That dispute is still being litigated.

In Utah, lawmakers passed a more limited Medicaid expansion this year, with work requirements and tighter eligibility rules, that is still waiting for the Trump administration’s blessing. Ward knows that most of his Republican colleagues in the legislature oppose the ballot measure. “I’m the black sheep of the family,” he said.

He says there’s long been support in the state as a whole for expanding Medicaid, but the decision has been left up to lawmakers mostly chosen by Republican primary voters. He’s eager to see if putting the question to a wider electorate leads to a different result.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Schoifet at mschoifet@bloomberg.net, Timothy Annett

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.