In Ohio Battleground, 2020 Race Will Be a Fight for the Suburbs

In Ohio Battleground, 2020 Race Will Be a Fight for the Suburbs

(Bloomberg) -- Donald Trump may not be able to count on the affluent Ohio suburbs that all modern Republican presidents have relied on to deliver winning margins in a must-win battleground state.

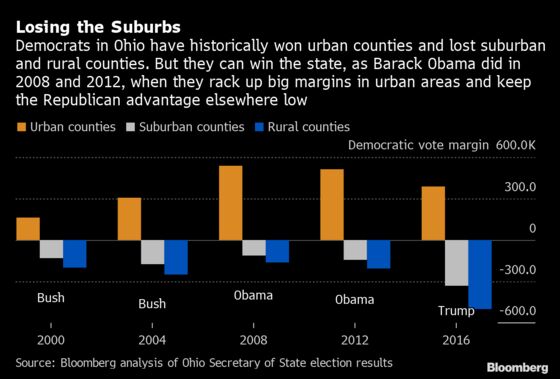

No Republican has ever won the White House without Ohio. So the Democratic formula for victory is to rack up big margins in the big cities — Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati — while reducing the Republican advantage in suburbs, smaller towns and rural areas.

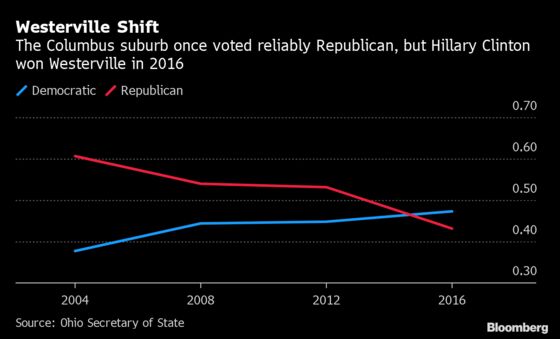

One affluent suburb, Westerville, population 40,387, is a warning sign for Republicans. The picturesque Ohio college town outside Columbus moved into the Democratic column in 2016 and stayed there in the 2018 midterm elections.

Otterbein University in Westerville will be the setting for Tuesday’s debate with the top 12 Democratic presidential candidates, giving the party a chance to use that backdrop to make a case about their appeal to educated suburban voters perhaps fatigued by three years of the Trump presidency.

“Westerville is symbolic of a whole lot of parts of Ohio that are not just seeing a subtle shift or a marginal shift, but a massive shift in voting,” said David Pepper, chairman of the Ohio Democratic Party.

“These places were the prior base of the pre-Trump Republican Party, and they’re turning blue — or at the very least the Republican margin is being whittled away to almost nothing.”

Westerville and places like it are rare bright spots for Democrats in Ohio, where Trump won all but eight of the state’s 88 counties, including one former Democratic stronghold that hadn’t voted Republican since 1972, when Richard Nixon won 49 states against George McGovern.

In 2016, Trump won the predominantly suburban counties by large margins, but he was losing the upper-middle-class suburbs that were traditional havens for moderate Republicans.

Anytown, USA

Westerville was a small town of red-brick buildings before it became a booming Columbus suburb. Before Prohibition it was the national headquarters of the Anti-Saloon League, earning it the nickname of “The Dry Capital of the World.” The first new liquor permit wasn’t issued until 2006.

It’s the kind of middle-American Anytown, U.S.A. so prized by politicians that Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton campaigned there within hours of each other in 2008, two days before the state’s Democratic primary.

It was George W. Bush’s last stop before the 2000 Republican convention.

John Kasich, the former Ohio governor who was the last Republican presidential candidate to concede to Trump in 2016, lives just outside of Westerville and represented it in the State Legislature and in Congress.

Once a reliably Republican stronghold, Westerville has been trending Democratic for some time. While Bush topped John Kerry by 23 percentage points in 2004, Mitt Romney beat Obama by only 8 percentage points in 2012 and Clinton defeated Trump in Westerville by 4 percentage points in 2016.

The largest employer is JPMorgan Chase, which develops its consumer banking technology there. The median household income is $86,466 — 60% higher than the rest of Ohio.

In response to Obama’s election in 2008, Westerville developed an active Tea Party movement. But there’s been a reversal in political energy since Trump’s victory in 2016, according to Mayor Craig Treneff.

Treneff considers himself a moderate Democrat, though the mayor’s job is non-partisan. He was selected by his fellow council members, a majority of whom are Republicans. He speculated that much of the shifting partisan support in the city can be traced to Trump’s election and moderate Republicans moving away from their party.

“I certainly know a lot of moderate Republicans in this town who I think have retained Republican identification but aren’t necessarily voting for a lot of Republican candidates these days,” Treneff said.

And there are Westervilles all over Ohio.

In Blue Ash, outside of Cincinnati, Democrats at the top of the ticket did 17 points better in 2018 than in 2012. In Hudson, north of Akron, Democrats closed the gap by 16 points. And Rocky River, west of Cleveland, has shifted 13 points in the Democrats’ favor.

One thing those suburbs all have in common: More than half of all adults have at least a bachelor’s degree.

Finding those shifting Republican voters is a key part of the Democratic strategy in Ohio.

“To win these suburbs, you have to get people who have voted Republican at some point,” said Aaron Pickrell, who managed Obama’s 2008 campaign in Ohio and was a senior adviser for his 2012 re-election. “You have to persuade them why you’re the better candidate.”

Kyle Kondik, author of “The Bellwether: Why Ohio Picks the President,” said that there are also suburbs with a less-educated populace that trended the other way in 2016. Democrats need to win those back if they expect to carry the state.

Parma, Cleveland’s largest suburb, is 18% college-educated. It went to Obama by more than 14 percentage points. Boardman Township, outside Youngstown, is 32% college-educated. Obama won it by 19 points. And Barberton, a working-class Akron suburb famous for its fried chicken, is 13% college educated. It went for Obama by 20 points. Trump won all of those in 2016.

Issues that could win over those voters include health care, education foreign affairs and gun control, Pickrell said.

Gun control is particularly salient in Ohio’s suburbs after a mass shooting in Dayton killed 10 people and injured 27 in August. In response, Governor Mike DeWine, a Republican, proposed universal background checks and a “red flag” law that would give judges the power to seize guns from people deemed a threat. DeWine, who won election last year by defeating Richard Corday, the chief of Obama’s Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has since backtracked on those proposals.

Democrats aren’t just courting educated suburban women as voters -- they’re also recruiting them as candidates. Mary Lightbody, who has a doctorate in science education and has taught at Otterbein, won election as a state representative last fall. She was one of three Democratic women who won what had been Republican districts in Franklin County suburbs that year. She credits a focus on issues like health care that appeal to women voters.

“A large measure of what happened is that more women are getting involved in our voting in greater numbers,” Lightbody said.

Bob Paduchik, a former Republican National Committee co-chairman who ran Trump’s campaign in Ohio in 2016 and is a senior adviser for his re-election effort, said Democrats are talking about flipping suburbs because they can’t counter the president’s economic record.

Flipping the Argument

“They’ve got nothing to talk about, and when a campaign or a party has nothing to talk about, they resort to these kind of process-type arguments on how they’re going to win,” Paduchik said.

And he said that Trump flipped Democratic counties and did well in reliably Democratic areas, including in and around Youngstown in northeast Ohio.

That’s a problem for Democrats, said David Cohen, a political science professor at the University of Akron and co-author of “Buckeye Battleground: Ohio, Campaigns, and Elections in the Twenty-First Century.”

“They don’t talk much about other parts of state trending the other way, such as the Youngstown area,” he said. But in the long term, Ohio Democrats may have demographics on their side.

“The good news for Democrats is that the Columbus area is the fastest growing part of the state,” he said.

To contact the reporters on this story: Gregory Korte in Washington at gkorte@bloomberg.net;Mark Niquette in Columbus at mniquette@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Wendy Benjaminson at wbenjaminson@bloomberg.net, John Harney

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.