In California, Costly Spectacle Looms in Bid to Oust Newsom

In California, a Costly Spectacle Looms in Battle to Oust Newsom

(Bloomberg) -- The effort to recall California Governor Gavin Newsom is shaping up to be an expensive national spectacle as unlimited fund-raising and partisan interests converge in the most populous U.S. state.

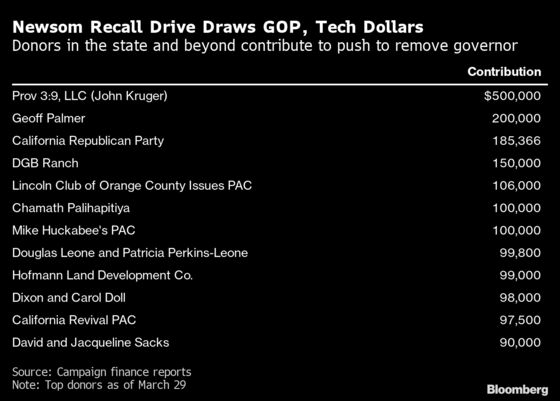

On one side are the state Republican party and tycoons including investor Chamath Palihapitiya, who are seeking to remove the ambitious Democrat amid anger over the pandemic and strict business shutdowns. Newsom comes armed with a stash of wealthy contributors and backing from prominent progressive figures such as Stacey Abrams and Elizabeth Warren.

The battle to oust Newsom more than halfway through his first term marks a dramatic turn from a year ago, when the governor enjoyed national recognition for his coronavirus response. In a state where ballot measures routinely shatter records as companies dish out millions of dollars to sway voters -- almost $700 million in 2020 alone -- a recall election in an era of hyper-partisan politics and social-media scrutiny promises to be especially costly.

“With no fund-raising limits, we could see a hundred million dollars or more being spent on each side of the recall with multiple serious candidates,” said Rose Kapolczynski, a consultant who worked for Newsom’s main Democratic rival, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, in 2018.

An election is not yet certain, but appears likely based on the number of signatures gathered in support of a recall. If enough are verified, voters will face two questions: Should Newsom be removed, and if so, who should replace him. There’s no cap on how much the governor and recall proponents can raise on the first part, while candidates running for the job are subject to limits. The election would likely come in November, according to California Target Book, which tracks state politics.

It would be the first gubernatorial recall since 2003, in which Gray Davis was removed and replaced by Hollywood superstar Arnold Schwarzenegger, a Republican, in a bizarre campaign that featured more than 130 candidates, including a porn star and a bounty hunter. And that was before Twitter and TikTok.

“This is going to be an ongoing circus,” said Anne Hyde Dunsmore, a campaign manager behind the recall.

The recall campaign’s momentum grew after a maskless Newsom attended a swank Napa Valley dinner party for a lobbyist friend in November while his administration told residents to eschew large holiday gatherings. It accelerated as California’s virus outbreak intensified through the winter and spurred new lockdowns.

While Newsom’s approval ratings have faltered since last year, he’s still running ahead: if the election were held today, 56% of likely voters in the heavily Democratic state said they oppose the recall, according to the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California poll released Tuesday. His job approval rating stood at 53%, about the same from a January survey.

But California’s quirks make it impossible for Newsom to take any lead for granted. A simple majority of yes votes on the first question on the ballot on whether he should be recalled will result in his ouster. Whoever wins the most votes on the second question on who should replace him -- even if less than 50% -- would become the next governor. And Newsom can’t by law appear as a candidate for that.

The threshold for his potential replacements to appear on the ballot remains low. Any registered voter able to garner 7,000 signatures or about $4,000 for a filing fee can run.

Fighting Back

Several Republicans have already said they will run. And national Republicans have jumped into fundraising, with Mike Huckabee’s political action committee kicking in $100,000 for the recall drive. The Republican Governor’s Association started its own committee to collect contributions for the recall last month.

“You can see that we’re going to raise the money because people are jumping in like crazy people. There’s money talk flying all over the place,” said Hyde Dunsmore, whose committee along with another has raised about $4 million for the recall. “It’s not a question of how much. It’s going to be, through what committee?”

After months of ignoring his opponents’ momentum, Newsom finally launched a campaign last month when the last batch of signatures was due, appearing on national television shows to describe the recall as an attempt by Republicans to rally their base after President Donald Trump’s defeat.

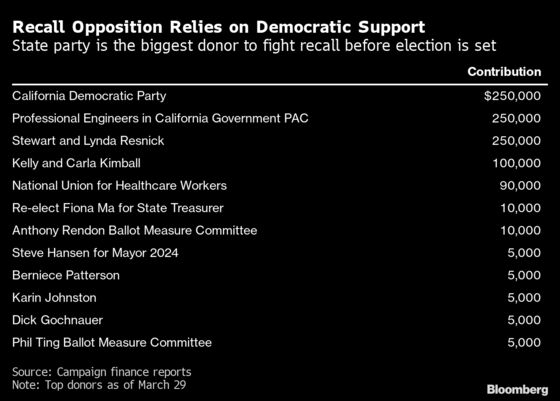

Major donors opposing the recall include the pomegranate and nut magnates Lynda and Stewart Resnick and the state party, filings show.

Nathan Click, a spokesperson for Stop the Republican Recall, said Thursday that the campaign raised $3.1 million since March 15, with more than 100,000 donations. The average online contribution was $22.40, he said.

“There is a lot of pent-up energy that is ready to fight for the governor and against the Republicans,” said Dan Newman, a spokesperson for the anti-recall drive.

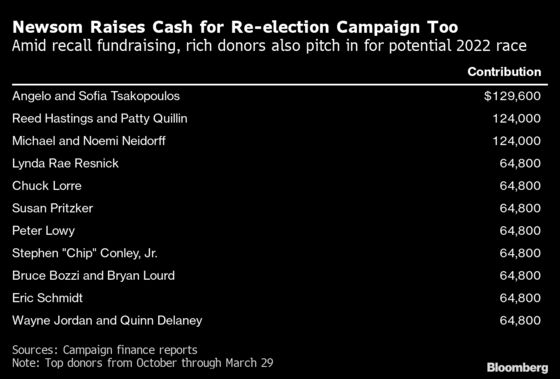

Newsom has a powerful fundraising mechanism in place, pulling in about $50 million for his 2018 gubernatorial landslide victory, according to FollowTheMoney.org, which tracks political contributions at the state and local level. His biggest donors were labor unions such as the powerful California Teachers Association, as well as corporate interests such as Blue Shield of California, a San Francisco-based health insurer.

Fund-raising will probably ramp up in September when California officials set the date for the election, said Steven Maviglio, a consultant who was press secretary for the recalled Davis.

The campaigns for and against the 2003 recall raised $28.3 million, with those opposing accounting for 70% of that, state records show. Candidates raised an additional $35.7 million, according to the National Institute on Money in Politics. Combined and adjusted for inflation, that’s about $90 million today.

That race, which was fueled by Davis’s handling of the state’s energy crisis, wasn’t “nationalized too much,” Maviglio said. “We have become a much more partisan country since then.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.