In Britain’s Clash of Radicals, There’s Nowhere to Hide

In Britain’s Clash of Radicals, There’s Nowhere to Hide

(Bloomberg) -- In the week Boris Johnson became British prime minister, two men in northeast England were jailed for throwing bricks through the office windows of their local member of Parliament in a politically motivated attack.

The lawmaker, Helen Goodman, voted to stay in the European Union. People in her district of Bishop Auckland voted overwhelmingly to leave and she says she regularly receives a torrent of abuse online over her Brexit stance. Her seat, held by the Labour Party for the past 84 years, is now a prime target of Johnson’s Conservatives.

The problem for Goodman is that she wants a compromise—a version of Brexit that keeps close ties with the continent—but compromise isn’t on offer. “What’s happened since the referendum is there’s been quite a lot of polarization,” she said. “So people who were very ‘Brexity’ before are even more ‘Brexity’ now and people who voted remain are even more ‘Remainy.’”

To suggest that Britain’s election campaign will be the most vitriolic in living memory is an understatement as parties dig in over if, when and how to leave the European Union. But the danger is that the radicalization of the country’s political system also looks entrenched.

Europe has seen its fair share of populists over the past five years, though whether it be Syriza in Greece or the Five Star Movement in Italy, they pitted themselves against the establishment before being brought to heel by the realpolitik of an integrated continent. What makes Britain different also makes its politics all the more febrile: it’s radical versus radical, with both cajoling an angry electorate.

Goodman, 61 and a parliamentarian since 2005, is defiant and is campaigning to retain her seat, but many others in Westminster aren’t. The list of electoral casualties is lengthening as more moderate members of Parliament quit or are pushed out.

Culture Minister Nicky Morgan on Wednesday announced she wouldn’t stand while former cabinet colleague Amber Rudd was barred from running for a seat as a Conservative as the party blamed her for disrupting Brexit. Morgan, along with former Conservative Heidi Allen, cited abuse for doing their job when announcing they would not contest the election.

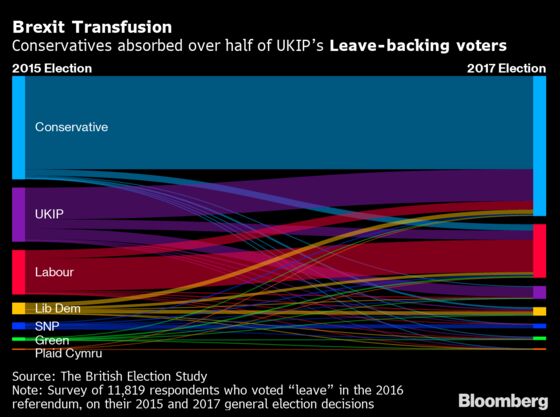

“If you’re a politician who stands in the center ground on Brexit, you’re just going to be losing to more extreme parties on either side of you,” said Jonathan Mellon, a research fellow in politics at the University of Manchester. “It’s only by taking a position that’s as extreme as the smaller parties that the larger parties can hope to win.”

Both Johnson and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn accuse the other of representing the worn-out establishment, saying only they are championing people left behind by globalization.

Corbyn, 70, is trying to steer the debate away from Brexit and onto the fraying of Britain’s social contract. He’s promising to nationalize utilities, reduce the working week to four days and scrap student tuition fees. Johnson, 55, is making the Dec. 12 vote all about his quest to “Get Brexit done” after he was forced to seek an extension until the end of January by Parliament. He needs to neutralize the campaign by arch-Euroskeptic Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party.

The two parties that have claimed the center ground, meanwhile, also have flagship policies that reflect the polarization of British politics. The Liberal Democrats are threatening to halt the departure from the EU all together while the Scottish National Party’s core policy is to end the United Kingdom and get independence for Scotland.

The Conservatives lead Labour by 10 percentage points on average, which would give them back the majority in Parliament they lost two years ago. That said, surveys suggested Johnson’s predecessor, Theresa May, would sail home in 2017 only for her to witness unexpected surge in support for Corbyn.

Johnson needs to attract voters who have left Labour for the Brexit Party, while Corbyn needs to appeal to voters who want to stay in the EU and support the Liberal Democrats, said John Curtice, politics professor at Strathclyde University in Glasgow and Britain’s leading psephologist. “You’re talking about which of these parties manages to lose less,” he said.

From areas like Kensington, home to London department store Harrods but also housing projects with some of the capital’s worst poverty, to places like Bishop Auckland with some of the country’s highest unemployment, Brexit has redrawn tribal divisions and thrown up battlegrounds that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Once one of the safest Conservative seats in the country, Kensington voted to stay in the EU and swung dramatically to Labour in 2017, with voters drawn to Corbyn’s softer Brexit stance. Labour snatched victory by just 20 votes. Now it’s too close to call between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, though Labour also has retained support.

Janette Froud, a market stall owner in Portobello Road, will vote for Labour just to stop any renewed prospect of leaving the EU without a deal to secure trade. “I would vote Lib Dem if I could afford to, but they’re probably not going to get in, so I would vote tactically,” she said.

Back in Bishop Auckland, Johnson needs to smother claims by Corbyn that a decade of austerity is responsible for the North East’s lagging average incomes, productivity and employment levels. Instead, he has to persuade them that leaving the EU and curbing immigration is the answer. Corbyn, meanwhile, needs to defeat the Liberal Democrat party, which says he’s pro Brexit because he refused to take sides and Labour now wants another referendum.

The plan is already working for people like Phil Mason, and that leaves Labour lawmaker Goodman clinging to her majority of just 502 votes. Mason, 66, reflected how, like many people in the former mining town, he has voted Labour all of his life and could never have considered backing a Conservative—until Johnson came along with his hard line on Brexit.

“Boris is wanting to get us out,” said Mason, a retired factory worker. “Jeremy Corbyn keeps changing his mind. I don’t think he has a clue what he wants to do.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tim Ross at tross54@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.