If Only Leaders Meeting in Paris Could Agree on WWI’s Lessons

Versailles settlement shows need for more ‘realism’ today

(Bloomberg) -- French President Emmanuel Macron hosts leaders from around the globe this weekend to commemorate the end of World War I, an effort to unite them against the kind of nationalism that drove the conflict a century ago and which appears to be gaining strength again.

That task might be easier if the 69 countries expected could agree on what the 1918 armistice meant.

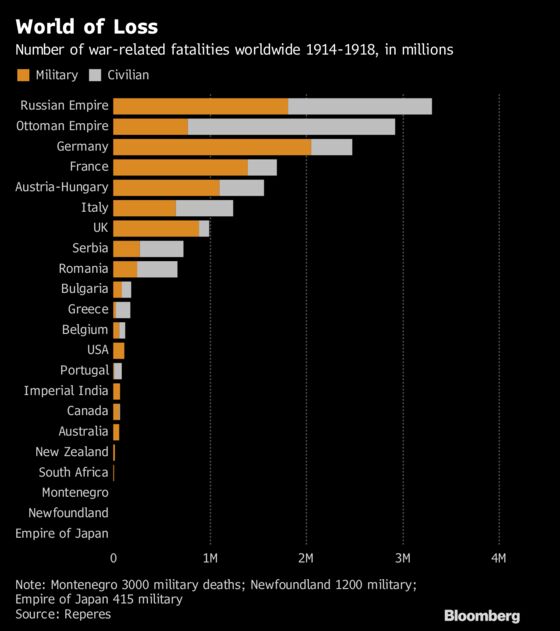

The “Great War” collapsed three empires, killed as many as 20 million people, ushered in the future Soviet Union and set the conditions for an even deadlier conflict to follow. Few of the leaders gathering in Paris would argue it was anything but a catastrophe, with an act of nationalist terrorism as its spark.

Yet the countries represented by Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Donald Trump and others fought very different wars, for varied goals and with dramatically contrasting consequences. For some, the German surrender on Nov. 11 was just a starting gun for further bloodshed.

There was a failure in 1918, as today, to understand and address the interests and positions of other states, according to Dominic Lieven, a Cambridge University historian of czarist Russia. That makes the war’s lessons as much about the ideologically driven miscalculations of the postwar period as about the nationalism that began it.

Versailles Failings

“Realism,” says Lieven, asked what the leaders should learn from Sunday’s commemoration. He cites the postwar Versailles settlement, which attempted to build peace in Europe by excluding Germany and newly Soviet Russia—the continent’s rising powers—as a tragic example of realism’s absence, leading to the return of war in 1939.

Instead of binding all great powers to the peace, France and Britain relied on the “hot air” of the League of Nations and alliances with much weaker countries to keep it. “We’re back in that territory now,” says Lieven, one of a number of historians who in recent years have written books challenging the dominant Western narrative of the Great War as a battle fought in the trenches of France and Belgium to turn back a tide of German nationalism.

Lieven’s contribution, Toward the Flame: War and the end of Tsarist Russia, opens with the line: “As much as anything, the First World War turned on the fate of Ukraine”—and an acknowledgment that many English speakers will think he’s “crazy” to say so. The conflict, says Lieven, began as a struggle between Germany and Russia to control the lands between them, from Serbia to the Baltic States.

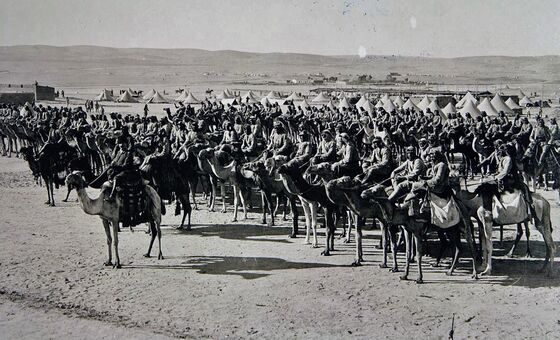

The four-year conflagration also redrew the borders of the Middle East across sectarian and ethnic fault lines that are still erupting today, in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere. It left France and the British Empire fatally weakened, and turned the U.S.—which joined the conflict in 1917, with a standing military of just 130,000 and ended it with 4 million—into a global superpower.

Ottoman Empire

Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Mahmoud Abbas, in particular, are likely to arrive in Paris with very different assumptions about the war. The 1917 Balfour Declaration of British support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine enabled the eventual creation of Israel, and with it the expulsion of Palestinians.

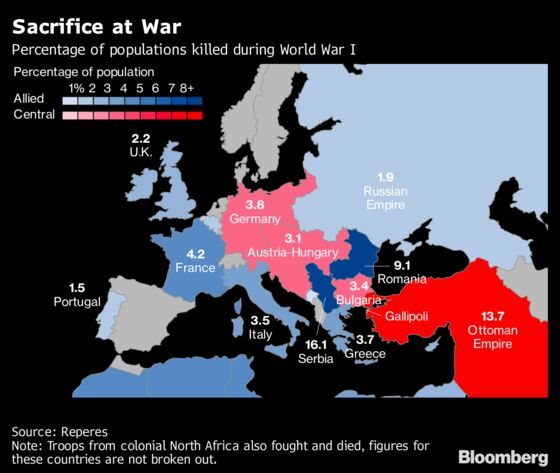

Casualty figures make brutally clear that the Western front was just one theater for the carnage. The Russian Empire lost more soldiers than either France or Britain. The Ottoman Empire, stretching from Istanbul to Yemen, saw almost 14 percent of its population killed, to Germany’s 4 percent. And the killing didn’t stop on Nov. 11.

“There was a conscious decision by Britain and France to carve up the Ottoman Empire, to reward their war effort, because by the end of the war they really had a difficult time justifying what it had been for,” says Eugene Rogan, author of another reinterpretation, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East. “They tried to justify it to their people by gaining pieces of territory.”

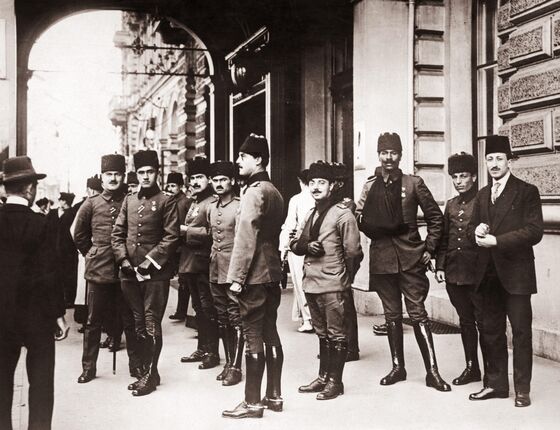

That has left Turks with a lasting ambivalence toward the war and the West in general. Every year, Turkey celebrates its defeat of the allied powers at Gallipoli, on the Dardanelles strait, in 1916, but not the Nov. 11 armistice.

Ataturk’s Battle

“As a Turk, if you commemorate 11 November, they will accuse you of stabbing your own country in the back,” said Burcin Cakir, a post-doctoral fellow at Glasgow Caledonian University, where she’s researching British and Turkish narratives of the Gallipoli campaign. World War I for the Ottomans was really a continuation of the two Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913, in which the empire had lost nearly all of its remaining territory in Europe, she said. The government joined the Central Powers in 1914, in the hope of getting it back.

The November armistice in Paris ushered a new episode in this long war, when Armenia, Britain, France, Greece and Italy sought to divide much of the empire’s remaining Anatolian heartland between them. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s battle to drive them out, creating today’s republic, didn’t end until 1923.

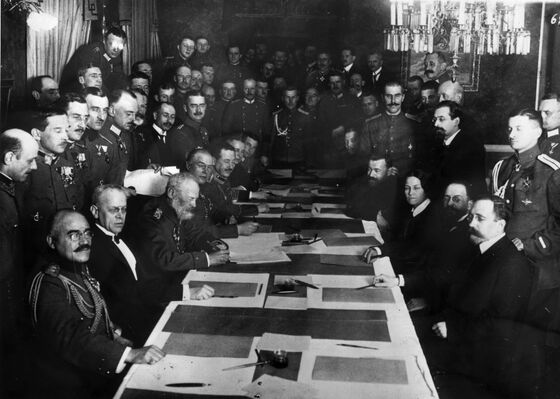

Russia also doesn’t commemorate Nov. 11; it had left the war already, in December 1917. The peace treaty it struck with Germany pushed Russia out of Central Europe, the Baltic States and Ukraine. The war had by then destroyed the Russian empire, collapsed a centuries-old monarchy and launched what would be 70 years of communist rule. Rather than bring peace, the November armistice freed allied troops to join Russia’s five-year civil war.

Gavrilo Princip

Even for Serbia, ground zero for the nationalism that was straining against Europe’s empires before 1914, Nov. 11 is little marked. That’s surprising, because not only did the Serbs emerge victorious, gaining a unified South Slav state, they also have a claim to having forced Germany’s surrender.

Germany’s capitulation took place when it still occupied swathes of Europe and not a single foreign soldier had set foot on its territory. The reason, according to James Lyon’s Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War, was the battle of Dobro Pole, in which Serbian, French and Greek troops broke through Central Powers lines from the South, in Macedonia. By the time the force reached the Danube River on Nov. 10, nothing stood between them and Berlin.

Yet Serbian leaders remain defensive about the blame associated with Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb, whose assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo had sparked the war. Memories of World War I are divisive to this day in the Balkans, where tensions are again rising along Bosnia’s sectarian frontiers. For many Serbs, according to Lyon, the West’s failure to prevent the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s reneged on the deal made at Versailles, after the armistice that world leaders will remember on Sunday.

Lieven, the Russia historian, points to the current tug of war between Moscow and the West over Ukraine as yet another example of the Great War’s unlearned lessons. “It’s all very familiar,” he says.

--With assistance from Samuel Dodge and Gregory Viscusi.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Alan Crawford

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.