Worst-Case Election Scenario: A Pennsylvania Counting Meltdown

Worst-Case Election Scenario: A Pennsylvania Counting Meltdown

(Bloomberg) -- It’s the morning after the Nov. 3 election, and the world doesn’t know who won the U.S. presidency because there are hundreds of thousands of mail-in ballots in the pivotal state of Pennsylvania that won’t be counted for days as lawyers descend to battle over the votes.

That’s the worst-case election scenario emerging if the race is so close that a single state will determine whether President Donald Trump or Democratic nominee Joe Biden has the necessary 270 Electoral College votes to win the White House.

In 2000, the race came down to fewer than 600 votes in Florida. This year, with a record number of mail-in votes expected to be cast because of the coronavirus pandemic, Pennsylvania is perhaps most at risk for a post-election meltdown because of a confluence of factors, according to experts in election administration and law.

The commonwealth is new to mail-in voting and took weeks to count ballots during its June 2 primary. Counties can’t start processing ballots until Election Day, virtually guaranteeing they won’t all be tabulated by that night. Pennsylvania was decided by only 44,292 votes in 2016, and its election laws allow for ballot challenges and appeals to drag on, increasing the risk for delayed results.

“We’re all bracing ourselves for a circumstance where we’re going to be under the microscope from the rest of the country and the rest of the world,” said Patrick Christmas, policy director for the Committee of Seventy, a nonpartisan civic organization in Philadelphia that focuses on election law and voting.

Pennsylvania may not be alone. The crucial swing states of Wisconsin and Michigan could also find themselves in a similar predicament, since they also can’t begin processing mail-in ballots until Election Day. But Pennsylvania, with its 20 Electoral College votes, has the highest odds of any state of being the tipping point in the election, according to an analysis by the FiveThirtyEight website.

Judging by how Pennsylvania performed in its June primary, there’s plenty of reason for alarm. Officials had changed election rules back in October 2019, well before the outbreak of the virus, to allow voters to request a mail-in ballot without having to provide an excuse. In the June primary, almost 1.5 million people cast votes by mail or absentee -- increasing to 51% of the total vote from 2% in the 2018 primary.

It took almost three weeks for all 1.5 million mail-in and absentee ballots in the commonwealth to be tabulated. About half the counties were still counting more than a week after the primary, according to a state report. Philadelphia, the most populous, didn’t even start counting mail-in votes until the day after the primary while it focused on in-person voting. Officials there needed 15 days to complete the count.

In November, officials expect the number of mail-in voters to double to about 3 million.

The race is also shaping up to be very close. Biden’s advantage in Pennsylvania has been narrowing since July, and he now holds a lead of 3.8 percentage points over Trump, according to a RealClearPolitics average of recent polls.

Trump, who has frequently repeated unfounded conspiracies of fraud with mail-in votes, has said he’ll be ahead in Pennsylvania before the outstanding mail-in votes are counted -- and that the only way he’ll lose the election is “when the other side cheats.”

Biden, who like Trump has made multiple trips to Pennsylvania, said last week that Trump and his Republican allies are trying to “throw into question the legitimacy of the election.” The former vice president urged Pennsylvanians to make a plan now to vote.

Pennsylvania is taking steps to scale up for Nov. 3. Counties are investing millions of dollars on new ballot sorters, high-speed scanners and other equipment and staff to handle the projected 3 million mail-in ballots for the Nov. 3 election. Even with those upgrades, many elections officials still think it could take days to count them all if the state legislature doesn’t change a law forbidding them to start processing ballots until 7 a.m. on Election Day.

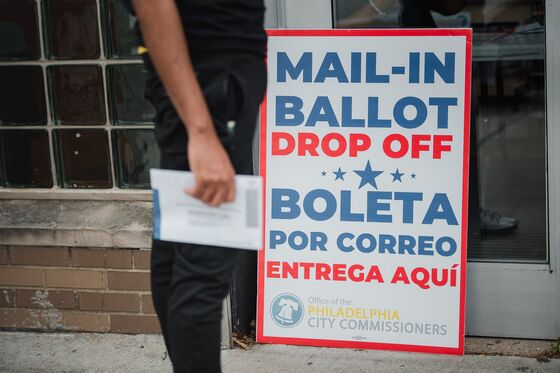

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court also ruled on Sept. 17 that mail-in ballots can be accepted up to three days after the election, and that counties can use drop boxes to collect mail-in ballots. Trump’s campaign has sued in federal court to challenge how drop boxes can be used and allow poll watchers in a county even if they don’t live there as now required by commonwealth law.

While voting advocates hailed the ruling allowing ballots postmarked before the election to be counted, it could add to the number of uncounted ballots after Election Day if counties can’t start processing them early and voters wait until the last minute, said Lisa Schaefer, executive director at County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania.

“It makes it very likely that many of our counties will not be able to complete it that day,” said Schaefer said of the counting of mail-in ballots.

In Philadelphia, the city is using a $10 million grant from the nonprofit Center for Tech and Civic Life to rent 125,000 square-feet of space in its convention center to install new equipment and staging areas with the ability to tabulate about 200,000 mail-in ballots on Election Day, said Commissioner Omar Sabir.

But as many as 350,000 or more ballots are expected, and even with teams working around the clock, it could take 36 hours after the election or longer to finish the counting because envelopes have to be cut open and ballots extracted, flattened and run through scanners -- all with the risk Covid could hit workers and disrupt the operation, he said.

“We’re not going to have all those mail ballots completed on election night,” Sabir said. “It’s not going to happen. It’s just not.”

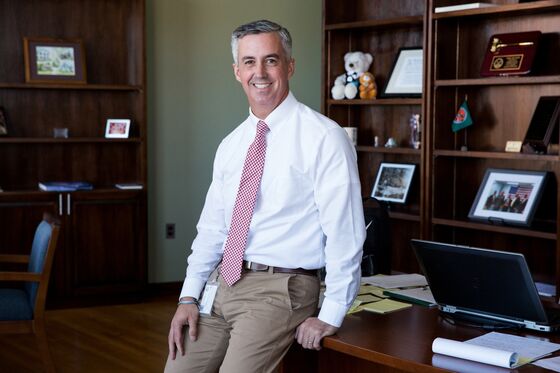

Bucks County outside of Philadelphia is a battleground where Hillary Clinton topped Trump by only 2,699 votes in 2016 and Barack Obama edged Mitt Romney by 3,942 votes in 2012. The county is adding equipment including a 40-foot ballot sorter it calls “the dragon” but still expects it’ll take at least two days after the election to process as many as 250,000 mail-in votes, Commissioner Bob Harvie said.

The Pennsylvania House passed a bill on Sept. 2, now before the Senate, that would allow counties to begin processing mail-in votes three days before the election. But its future is uncertain since Democratic Governor Tom Wolf has threatened to veto the measure because it would also ban drop boxes and make other changes that Democrats oppose and Republicans are livid about recent election rulings by the Democratic-majority state Supreme Court.

“We’re operating under the assumption that nothing’s going to change,” Harvie said.

None of these preparations address another significant potential problem: mail delivery of ballots. The U.S. Postal Service warned the Pennsylvania secretary of state in a July 29 letter that the commonwealth’s requirement for all mail-in ballots to be received by 8 p.m. on Election Day and the ability for voters to request a ballot as late as seven days before the election “appear to be incompatible” with USPS delivery standards. While the state Supreme Court’s extension of the timeframe for accepting ballots aimed to address that, risks of delays remain.

Mail service continues to be slowed in the Philadelphia area, despite a pledge from Postmaster General Louis DeJoy to halt changes blamed for poor service until after the election, said Nick Casselli, president of Local 89 of the American Postal Workers Union.

Slow mail could be a double whammy. Many mailed ballots need to move through the system twice, once to get to the voter and again, after being marked, to reach election officials.

Edward Foley, a professor and director of an election law program at Ohio State University, has studied disputed elections and said he is most concerned about Pennsylvania this year because it may be the most important state in determining the Electoral College winner, all the issues with mail-in voting, and election statutes that could allow the vote-counting process to be drawn out by ballot challenges and appeals.

Foley wrote a paper last year entitled, “Preparing for a Disputed Presidential Election” in 2020 that outlined a scenario with a delayed result in Pennsylvania sending to Congress votes from two different slates of electors to the Electoral College and no resolution by Jan. 20, 2021, when the next president is supposed to be inaugurated.

“They’re creating a false scenario because they want to be able to have ballots come in after Election Day,” Tabas said in an interview of Democrats.

One factor is what Foley calls a “big blue shift,” when mail-in votes that favor Democrats flip the unofficial result from election night from mostly in-person votes. With Trump railing against mail-balloting as rife with fraud, requests by Republicans are down this year -- raising concerns by Democrats that Trump will declare himself the winner based on election night returns and seek to reject or delegitimize the uncounted mail-in ballots.

Of the almost 2 million mail-in and absentee ballots requested in Pennsylvania through Sept. 17, 67% were from Democrats and only 24% from Republicans, according to the Department of State.

Pennsylvania could be in store for a situation similar to the recount fight in Florida in the 2000 presidential election that ended with a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, said Benjamin Geffen, a staff attorney at the Public Interest Law Center in Philadelphia.

“That is absolutely a possibility,” Geffen said. “It’s something that concerns everybody who’s working on elections and voting rights in Pennsylvania.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.