Supreme Court Lets States Stop ‘Faithless’ Presidential Electors

Supreme Court Lets States Stop ‘Faithless’ Presidential Electors

(Bloomberg) -- The U.S. Supreme Court said states can require members of the Electoral College to vote for the presidential candidate who won the statewide balloting in decisions that add a dose of predictability to the country’s complex election system.

The two unanimous rulings Monday alleviate a potential source of controversy heading into what could be a tumultuous November vote on President Donald Trump’s re-election bid. The court rejected contentions that the Constitution gives presidential electors the right to vote as they please no matter who won the state’s popular vote.

The Constitution and its 12th Amendment “give states broad power over electors, and give electors themselves no rights,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote for the court in a case from Washington state.

Electors are party members who are appointed to the Electoral College if their side’s candidate wins, and the broad expectation has long been that they will support that candidate. But in 2016, 10 “faithless electors” voted, or tried to vote, for someone other than Trump or Hillary Clinton. Only nine electors had voted for someone other than their party’s candidate from 1900 to 2012.

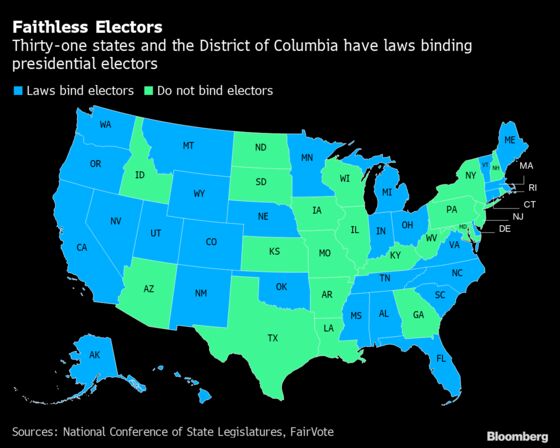

About 30 states attempt to bind electors to the winning candidate, though some of those states don’t penalize people who cast deviant votes.

Lower courts had been divided on whether states can enforce a requirement that electors vote for the state’s top vote-getter.

A federal appeals court ruled that Colorado violated the Constitution when it removed Michael Baca as an elector and canceled his vote. Baca, a Democratic elector, had voted for Republican John Kasich instead of Clinton, who won the statewide vote.

Risk for Trump

The Washington Supreme Court, however, upheld $1,000 fines imposed on three people who voted for former Secretary of State Colin Powell instead of Clinton. Washington changed its law last year so that electors would be removed, rather than fined, and their votes canceled, much like in Colorado.

Eight of the 10 faithless electors in 2016 were bound to Clinton. The group was aiming to encourage Trump electors to follow suit and deprive him of an Electoral College victory.

The Supreme Court’s decision makes similar scenarios less likely in the future, but not impossible. Although the court said states can penalize electors who fail to follow their pledges, it’s still up to the state legislature to decide how much discretion electors have.

Only 15 states impose some kind of penalty on faithless electors who break their pledges. Other states have no penalty, and some simply replace electors who fail to follow their pledges with those who will.

Faithless electors in 2020 may pose more of a risk to Trump than to Democrat Joe Biden. States that let electors change their votes went overwhelmingly for Trump in 2016, 154 electoral votes to 81.

Hamilton and Burr

In an opinion that made reference to the hit Broadway musical “Hamilton” and the HBO comedy “Veep,” Kagan said state efforts to control their electors date back to the 18th century.

“From the first, states sent them to the Electoral College -- as today Washington does -- to vote for preselected candidates, rather than to use their own judgment,” Kagan wrote. “And electors (or at any rate, almost all of them) rapidly settled into that non-discretionary role.”

The 12th Amendment was adopted after the election of 1800 resulted in an Electoral College tie between the two men on the Republican ticket that year, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The tie sent the contest to the Federalist-controlled House, where Alexander Hamilton’s influence helped secure the election of Jefferson. Hamilton later died in a duel with Burr.

“Alexander Hamilton secured his place on the Broadway stage -- but possibly in the cemetery too -- by lobbying Federalists in the House to tip the election to Jefferson, whom he loathed but viewed as less of an existential threat to the Republic,” Kagan wrote.

Under the 12th Amendment, electors vote separately for president and vice president.

The electors in the Colorado and Washington cases argued unsuccessfully that the 12th Amendment provides detailed instruction on how the electoral vote proceeds, precluding state interference once the electors are appointed.

Thomas and Gorsuch

Kagan described the election of 1796 as “fodder for a new season of Veep,” because it made the Federalist John Adams president with his rival Jefferson as vice president.

The Supreme Court ruled in both the Washington and Colorado cases Monday.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor disqualified herself from the Colorado case because of her friendship with one of the electors in the case. Although the outcome was unanimous in both cases, Justice Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch said they would have used different reasoning.

The Supreme Court ruled in 1952 that states could insist that electors pledge to support their party’s nominee, but the court had never said what, if any, enforcement steps states could take. Litigants on both sides of the issue had urged the justices to resolve the issue now to ensure it won’t arise in the middle of a disputed election.

Under the U.S. system, each state’s number of electors is equal to its representation in Congress -- two senators plus members of the House. Almost all states use a winner-take-all system, in which the candidate who wins the state’s popular vote is entitled to the full slate of electors. Two states, Nebraska and Maine, have systems that can produce a split electoral vote.

The cases are Chiafalo v. Washington, 19-465, and Colorado Department of State v. Baca, 19-518.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.